ECHOES OF THE HEAVENS THE ORION MYSTERY AND THE MATHEMATICS OF THE ANCIENT WORL

Let us begin with a question as old as human curiosity itself: What is a constellation? At its most basic, a constellation is a group of stars that, to the attentive human eye (with the exception of Gen Z or Gen Alpha eyes, however attentive they may proclaim to be!), forms a recognizable pattern - an animal, a mythological figure, or a symbol that can guide and inspire. In the ancient world, constellations were far more than aesthetic curiosities.

Let us begin with a question as old as human curiosity itself: What is a constellation? At its most basic, a constellation is a group of stars that, to the attentive human eye (with the exception of Gen Z or Gen Alpha eyes, however attentive they may proclaim to be!), forms a recognizable pattern - an animal, a mythological figure, or a symbol that can guide and inspire. In the ancient world, constellations were far more than aesthetic curiosities.

They were the original calendars and compasses of humankind. Farmers watched them to know when to sow and reap, and sailors used them to navigate the vast seas: find Ursa Minor, and you would find Polaris (the North Star) anchoring your latitude in a sky of wonders. Thus, began humanity’s enduring dialogue with the cosmos.

Among the stars, no celestial figure has captured the imagination more vividly than Orion, the hunter. Though the name Orion comes from Greek mythology, this constellation was visible and significant to many ancient cultures, not just the Greeks. Its bright belt of three stars (Alnitak or Zeta Orionis, Alnilam or Epsilon Orionis, and Mintaka or Delta Orionis) forms a straight line that has drawn human eyes up through millennia. What is remarkable is how often this pattern seems echoed not just in stories but in stone.

In Egypt, the cosmos and earthly life were intertwined in a tapestry of religion and mathematics. The stars of Orion were associated with Osiris, the god of fertility, agriculture, death, and the afterlife. Egyptians believed that the pharaoh, at death, became divine and joined Osiris in the heavens. The Great Pyramids of Giza thus stand not only as colossal tombs but as architectural monuments celebrating mortality, eternity, and the cosmic order. The pyramid builders oriented their monuments with astounding precision, aligning them to the cardinal directions and, scholars argue, to specific celestial phenomena such as the pole star of their age, Thuban, and potentially the stars of Orion’s Belt.

In 1989, Belgian engineer Robert Bauval noticed a curious pattern: viewed from above, the three great pyramids of Giza, Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, seem to mirror the three stars of Orion’s Belt, with the smallest pyramid slightly offset, just as Mintaka is slightly offset from the other two stars. This idea, developed alongside Adrian Gilbert as the Orion Correlation Theory and popularised in the 1994 book The Orion Mystery, suggests that the layout of these monumental tombs may have been intended as a terrestrial reflection of the celestial arrangement.

Proponents point to the precision with which the pyramids’ passages align to astronomical targets and the importance of Orion in Egyptian cosmology. Sceptics point out that this interpretation remains controversial and is classified by mainstream archaeologists as a fringe theory due to the lack of direct textual or archaeological evidence in Egyptian sources explicitly stating such intent. Yet even as the debate continues, the very possibility of such astronomical awareness in ancient design speaks to a broader truth: across continents and centuries, ancient peoples mapped the sky in stone.

This celestial impulse appears again in our own nation. Around the sacred city of Anuradhapura stand three monumental stupas, Mirisavetiya, Ruwanwelisaya, and Jetavanaramaya, built between the 2nd century BCE and the early centuries of the Common Era. Some researchers have noted that their triangular configuration on the ground forms a pattern closely matching the triangle of three stars on the right wing of Orion, a phenomenon termed heaven–earth duplication.

The idea that Buddhist architects might have mirrored Orion’s wing stars raises a fascinating question: Why should a Buddhist civilisation care about an Egyptian constellation? The short answer is that ancient cultures rarely separated celestial observation from lived experience. In Sri Lanka, astronomical knowledge was not merely abstract, it played a vital role in agriculture, helping farmers to anticipate the monsoon rains that drove rice cultivation. More subtly, Buddhist cosmology, while not centred on star gods in the way Egyptian religion was, nonetheless dwells in a vast and ordered universe. Many Buddhist texts contemplate innumerable worlds, eons, and cycles, suggesting a worldview in which the structure of the cosmos itself is meaningful. Alignments with celestial phenomena, then, may not have signified star worship per se, but a symbolic anchoring of sacred monuments within the unfolding order of existence.

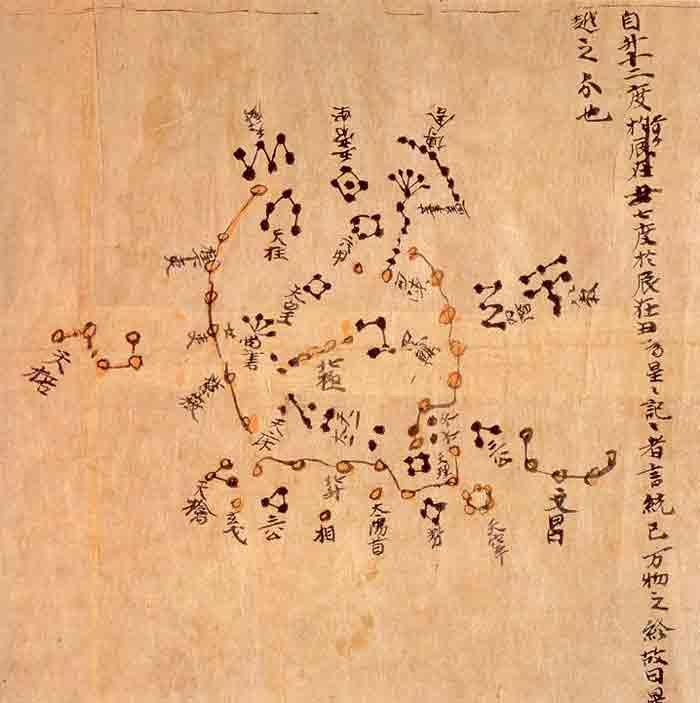

Elsewhere, too, the mathematics of ancient skywatchers left enduring marks. In Mesoamerica, the Mayans and their neighbours-built observatories and temples precisely aligned with solar and stellar events, demonstrating mastery of calendrical and astronomical cycles that rivalled anything in the Old World. In ancient China, astronomers charted the heavens with detailed star catalogues and created early star maps like the Dunhuang Star Chart, a complete graphical depiction of the night sky dating from the Tang dynasty.

These global echoes remind us that the night sky was a shared reference point, a constant canvas upon which diverse cultures projected their most profound questions. Were the great monuments of the ancient world mere stone? Or were they, in some sense, stargates - deliberate connections between human experience and the ordered beauty of the cosmos?

Whether one reads the evidence as confirming elaborate intentional alignments or as inspiring mythic interpretations, there is no escaping the wonder of the mathematics and ingenuity that ancient civilizations brought to their skyward gaze. From Egypt’s monumental pyramids to Sri

Lanka’s sacred stupas, from Mayan observatories to Chinese star charts, humanity’s earliest architects and astronomers sought to measure the heavens and understand our place within them.

In the end, the Orion mystery may not be one mystery but many - reflections of a common human urge to turn earthward questions into celestial answers. For in those distant stars lie not only lights of gas and fire but the ancient impulses of minds striving to grasp the infinite.