BY SHALEEKA JAYALATH

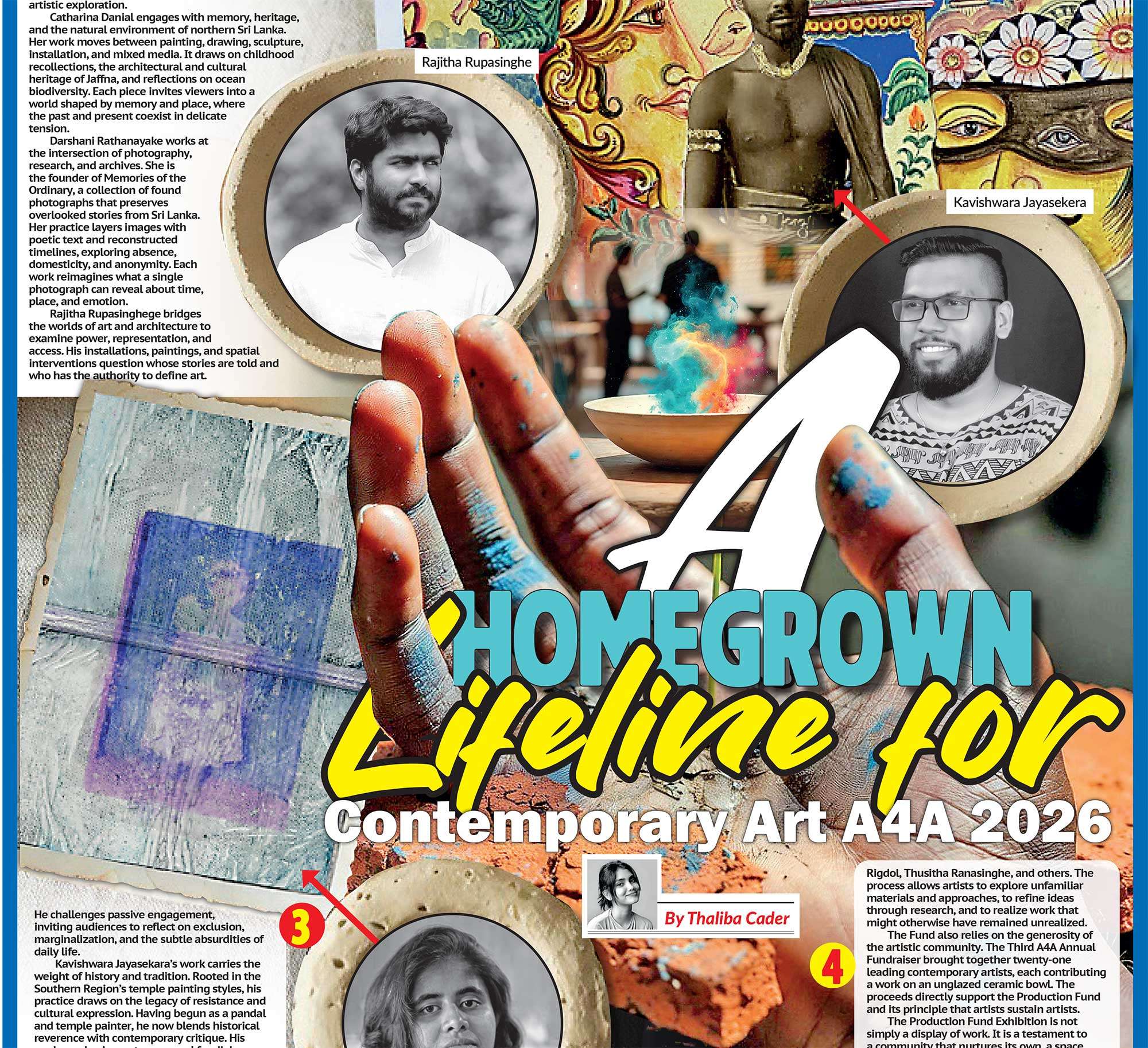

Kala Pola 2026 unfolded on the 8th of February along Green Path with a quiet confidence that comes only from longevity. Stretching further than ever before, with stalls extending into the adjoining park, this year’s edition felt physically expansive, almost symbolic of how deeply embedded the event has become in Sri Lanka’s cultural calendar. Those in want of something relaxing to do on a Sunday afternoon chose to wander around with ice cream cones. The younger generation made it a point to take selfies in front of the artwork, while a couple of serious photographers held up professional cameras in front of masks and copper works.

Kala Pola 2026 unfolded on the 8th of February along Green Path with a quiet confidence that comes only from longevity. Stretching further than ever before, with stalls extending into the adjoining park, this year’s edition felt physically expansive, almost symbolic of how deeply embedded the event has become in Sri Lanka’s cultural calendar. Those in want of something relaxing to do on a Sunday afternoon chose to wander around with ice cream cones. The younger generation made it a point to take selfies in front of the artwork, while a couple of serious photographers held up professional cameras in front of masks and copper works.

Meanwhile, the art lovers (both the seasoned ones in search of genuine talent, as well as the so-called in search of a bargain) moved from canvas to canvas in that familiar rhythm that Kala Pola has perfected over the past three decades. If scale alone were the measure of success, this may well have been the biggest Kala Pola yet. Conceptualised by the George Keyt Foundation and launched in 1993 with just 35 artists, Kala Pola has enjoyed the unbroken patronage of the John Keells Group since 1994, a rarity in sustained private-sector support for the arts in Sri Lanka. Over the years it has evolved into a one-day open-air exhibition hosting close to 300 painters and sculptors from across the island, attracting more than 20,000 visitors annually. In recent years, sales have exceeded Rs. 13 million, with several of the artists who displayed at Kala Pola going on to establish successful careers. These numbers matter because they speak not only to popularity, but to Kala Pola’s most significant achievement: transforming art from an elite, gallery-bound pursuit into a lived, public experience.

Inspired initially by the summer art fairs of European capitals such as Montmartre in Paris, Kala Pola has always promised more than visual spectacle. Its underlying rationale, which was to launch and sustain artistic careers, foster a clientele, facilitate the exchange of ideas, and promote art as a viable profession, addresses a long-standing gap in Sri Lanka’s cultural infrastructure. As artist Erushmie (Eru) Karunaratne observes, “Kala pola is a great opportunity to meet different artists and the only event held annually for artists across the island. Given the high demand, we as artists see the need for more events like this. Recognising local artists and providing them with inclusive opportunity is important.” Eru’s words point to a crucial reality: Kala Pola’s success also highlights how few comparable platforms exist. For many artists, this one day may represent the sole chance to showcase a year’s worth of work to a wide and varied audience, to earn income directly, and, with some luck, to be noticed by a discerning collector or influential figure in the art world. In a country where grants are scarce and institutional pathways limited; the stakes are high. The romantic notion of the starving artist does little to sustain creative practice; survival often depends on sales. It is within this context that Kala Pola must be understood.

The inevitable question, particularly in a year of such scale, is whether Kala Pola 2026 showcased anything genuinely new. The answer is nuanced. Much of what was on display could be described as contemporary, or at least contemporary as it tends to manifest within Sri Lanka. There were familiar reinterpretations and stylistic echoes: the visual grammar of the ’43 Group adapted for modern interiors, Picasso filtered through local sensibilities, even the Mona Lisa appearing in a painted, wooden block variation. These works were polished, accessible, and unmistakably commercial. Ground-breaking, however, would be a generous description. From the consumer’s perspective, this consistency is precisely what makes Kala Pola compelling. It is one of the few spaces where original art can be acquired at relatively affordable prices, where a living room can be transformed without the intimidation of galleries or the exclusivity of auctions. Like Montmartre, it offers an experience as much as an exhibition - a day for those with a Sunday to spare to stroll, eat, talk, and absorb art without obligation. In this sense, Kala Pola succeeds admirably in democratising access. For artists, the commercial orientation of much of the work is less a creative compromise than an economic necessity. In an environment where experimentation is rarely rewarded financially, sticking to what is known to sell becomes a rational, even responsible choice.

Expecting widespread risk-taking under such conditions may be unrealistic. The absence of radical experimentation at Kala Pola may say less about artistic courage and more about the structures within which artists operate. And yet, there is an unease that persists. Over time, Kala Pola has come to represent reliability rather than surprise. The visual languages repeat themselves, year after year, creating a sense that while the event grows larger, the artistic conversation remains largely unchanged. Is this necessarily a failure? Perhaps not. It may reflect consumer taste, or the limits of art education, or simply the comfort of the familiar. But it does invite reflection. Do we prefer consistency because it reassures us, or because we have not cultivated the appetite to engage with work that challenges us?

Kala Pola’s greatest strength may also be its defining constraint. As a mass, one-day event, it is designed for inclusion rather than provocation. Its role is not to disrupt but to normalise art as part of everyday life. In doing so, it builds cultural capital quietly, introducing thousands to the act of looking, choosing, and valuing creative labour. If that comes at the expense of experimentation, it may be a trade-off the ecosystem has tacitly accepted. Kala Pola 2026 was not a revolution. It was something steadier and, in many ways, more important: a reaffirmation. Of artists showing up, of patrons supporting without extracting profit, and of the public continuing to gather around art in an increasingly distracted world. In a cultural landscape where many initiatives flicker briefly and disappear, there is significance in an event that endures. Whether the future of Kala Pola lies in greater experimentation or in multiplying platforms like it across the country remains an open question, however its presence, unwavering and expansive, continues to matter.