FRANKENSTEIN: AMBITION, RESPONSIBILITY, AND THE MAKING OF MONSTERS

In the summer of 1816, an eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley sat by Lake Geneva alongside Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, and John Polidori to take part in a playful ghost-story competition among friends, little knowing she would ignite one of the most enduring works of English literature: Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus. By the time Mary Shelley was nineteen, the draft was complete. When the novel finally appeared in print in 1818, she was only twenty. Its author was young, untested, and more significantly, female in an era where women were rarely permitted to claim intellectual greatness.

This context matters. From around 1750 onwards, English women slowly began carving out space in the literary marketplace, yet writing for a living did not become socially or economically viable for women until the 1840s. Publication, recognition, and critical praise lay largely in the hands of men who could elevate a woman’s writing to fame or condemn it to obscurity. That an eighteen-year-old woman produced a work so philosophically daring, so scientifically provocative, so psychologically unflinching, remains extraordinary. Shelley dared to imagine not just a ghost, but life itself created from death; not just terror, but moral collapse; not just a monster, but the monstrousness within humankind.

And so we ask: what were the warped workings of Mary Shelley's mind that she would conceptualise something so macabre? The word warped may be unfair, but the question is essential. Shelley was raised among radical ideas - her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was a feminist philosopher, and her father Godwin an anarchist thinker. She absorbed conversations on science, revolution, and mortality from childhood. She experienced profound personal loss, including the death of her own infant. Shelley’s imagination was not “twisted” but informed by grief, genius, and an intellect unshackled from the conventions expected of young women. Her mind was expansive, curious, and fearless, willing to ask the questions society avoided.

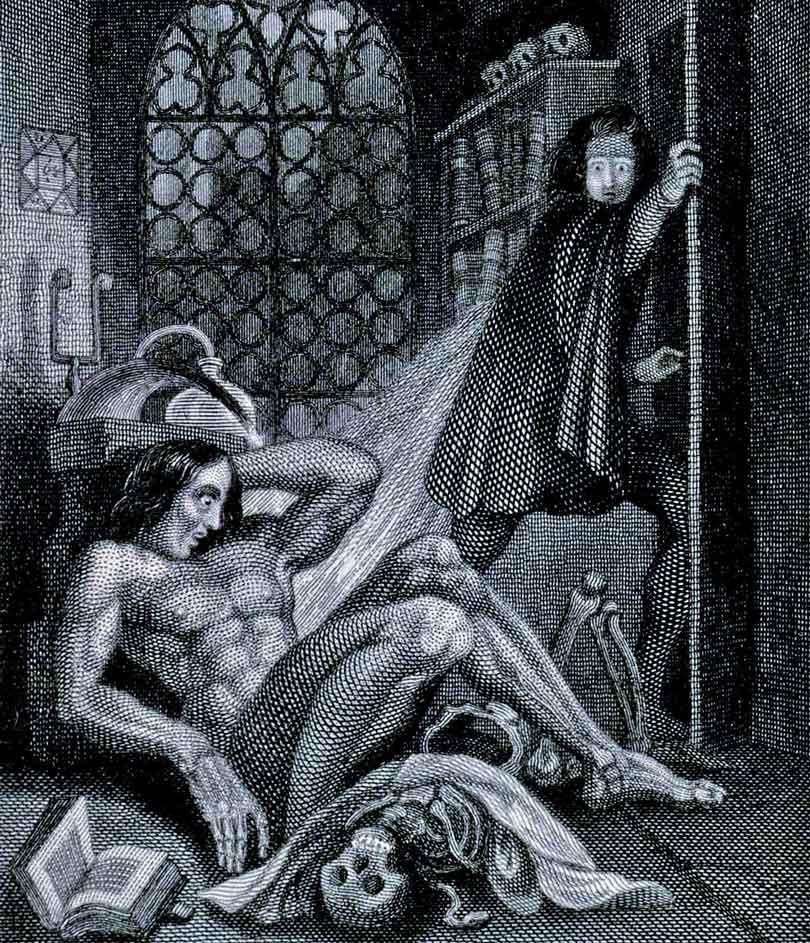

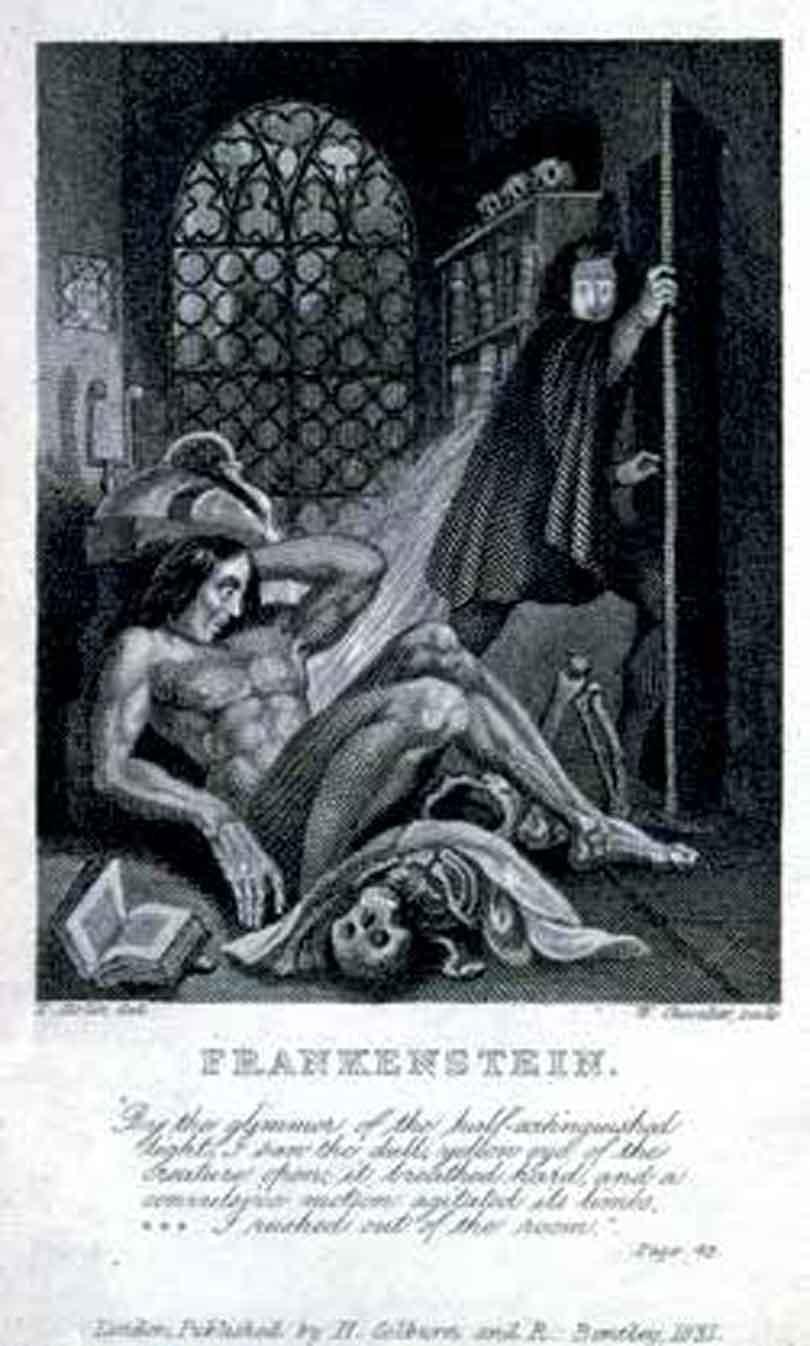

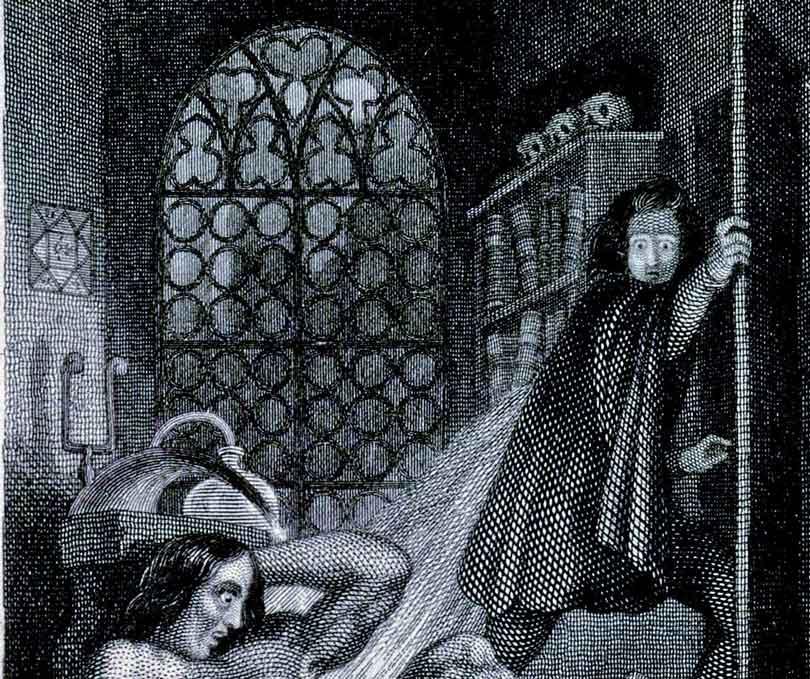

At the centre of Frankenstein stands the creature: huge, stitched, exiled, raging. Readers have asked for over two centuries: what does the monster represent? Is he an emblem of scientific hubris, or of society’s failure to embrace the outsider? Perhaps he is both victim and mirror. The world sees him as monstrous before he even speaks, and, rejected again and again, he becomes what they fear.

Yet the real question may be more unsettling still: is the true monster Victor Frankenstein? The creature is not born evil; he is made by a man obsessed with glory. It is Victor, not the creature, who commits the original sin: to create without responsibility, to pursue knowledge without morality, to give life without considering how to nurture it.

If anyone should answer for the creature’s suffering, it is not the creation but the creator. Victor unleashes the chain of events that follows yet recoils from accountability. And here Shelley’s novel steps beyond Gothic horror and becomes a reflection of ourselves. It invites us to ask: what monsters do we create through our choices? Agamemnon’s ancient reminder echoes across time: destiny always gives us a choice. It is we who set actions into motion. Victor had a choice: to think before he acted, to imagine consequences, to ask not only can I create life? but what kind of life am I shaping?

A recent adaptation attributes to Guillermo del Toro the line: did Victor think about the soul of the creature when he created it? Did he pause to consider the heart, the emotions, the gentleness or despair of the being he would unleash? In the original novel the creature is not intended to be immortal, but he is made impervious to illness and aging. Victor’s goal was to “banish disease… and render man invulnerable to any but a violent death.” His scientific dream may be argued to have been noble, even compassionate. Yet Shelley teaches us that even noble ambition can rot when it outruns empathy. To satisfy human yearning, Victor engineered a product (if one dares to call a sentient being a product) without contemplating spirit, morality, goodness, or love. In his ambition to conquer nature, he forgot what it means to be human.

This failure is not confined to literature. Shelley wrote a parable that resonates into the twentyfirst century - about artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and every innovation that promises power without caution. Frankenstein is not merely the tale of a monster, but a warning: progress without humanity becomes horror.

And beneath it all lies the final question that haunts the novel and our entire species: why do we search for immortality? Why do we stretch toward godliness, desperate to outrun decay, time, and death? Perhaps it is fear. Perhaps hope. Perhaps the belief that if we conquer mortality, we conquer meaning itself. Yet Mary Shelley suggests the opposite - that greatness comes not from defying death, but from understanding life. What gives us value is not eternity, but experience; not invulnerability, but compassion; not power, but responsibility.

In creating a monster, Shelley illuminated what it means to be human. Her novel endures because it urges every reader to look into the face of their own creation, be it a decision, an invention, a child, or a future, and ask of ourselves: Do I act with responsibility, or only with ambition? For in the end, it is not the monster we must fear.

It is the maker.