BEYOND THE SEAMS BY SHRI AMARASINGHE

BEYOND THE SEAMS BY SHRI AMARASINGHE

The global fashion industry produces between 100 and 150 billion garments every year.

The world’s population is just over 8 billion. Pause there for a moment. Even at the lower end of that estimate, that is more than twelve new garments per person, per year: every man, woman, and child. Not accounting for income levels, climate differences, cultural dress practices, or the simple reality that many people still repair, re-wear, and pass clothes down.

This is not a supply issue. It is not a creativity issue. It is an overconsumption problem; disguised as choice, affordability, and trend. For decades, the fashion industry has framed excess as progress. More collections. Faster cycles. Lower prices. Endless novelty. We were told this was democratization, fashion finally becoming accessible to all. But somewhere along the way, accessibility turned into disposability, and expression turned into extraction. Today, wardrobes are fuller than ever, yet satisfaction is thinner.

The Mathematics of Excess

Let’s be precise. The average person does not need twelve new garments a year. In many parts of the world, people comfortably live with far fewer. Historically, wardrobes were small, intentional, and repaired repeatedly. Clothes carried memory. They aged with the wearer. A loose seam or faded hem was not a flaw, it was evidence of life lived. Now, garments are engineered to be replaced, not repaired. Fibres are blended to prevent easy mending. Stitch density is reduced. Trends expire before fabrics do. The industry has normalized a model where clothing is worn fewer times than ever before, while production volumes climb higher each year. According to multiple studies, the average garment today is worn 30–40% fewer times than it was two decades ago. This is not consumer failure alone. It is systemic design.

Overproduction Is Not an Accident

Fashion overproduction is often discussed as an unfortunate side effect of demand. This is misleading. Overproduction is a deliberate business strategy. Retail models rely on abundance because abundance creates urgency. Overflowing racks signal choice. Excess stock allows brands to test trends with minimal risk-produce more, sell what sticks, discount the rest. Unsold garments are written off as inventory loss, destroyed, incinerated, or quietly dumped into secondary markets in the Global South. This is not inefficiency. It is an externalized cost.

- The environmental cost is carried by landfills and waterways.

- The social cost is carried by garment workers under pressure to produce faster and cheaper.

- The cultural cost is carried by consumers trained to see clothing as temporary.

And the moral cost? That belongs to all of us who have accepted this pace as normal.

When “Affordable” Becomes Expensive

Fast fashion prides itself on affordability. But affordable for whom, and at what cost? Cheap garments are rarely cheap in reality. They are subsidized by low wages, unsafe working conditions, chemical-heavy processes, and environmental degradation. The true price is simply paid elsewhere, by rivers turned toxic, by communities living near landfills, by workers who cannot afford the clothes they make. Ironically, overconsumption also costs the consumer more. Buying ten poorly made garments that lose shape after a few washes is far more expensive than investing in one well-made piece that lasts years. Yet we are rarely taught to calculate value this way. We are taught to chase novelty, not longevity.

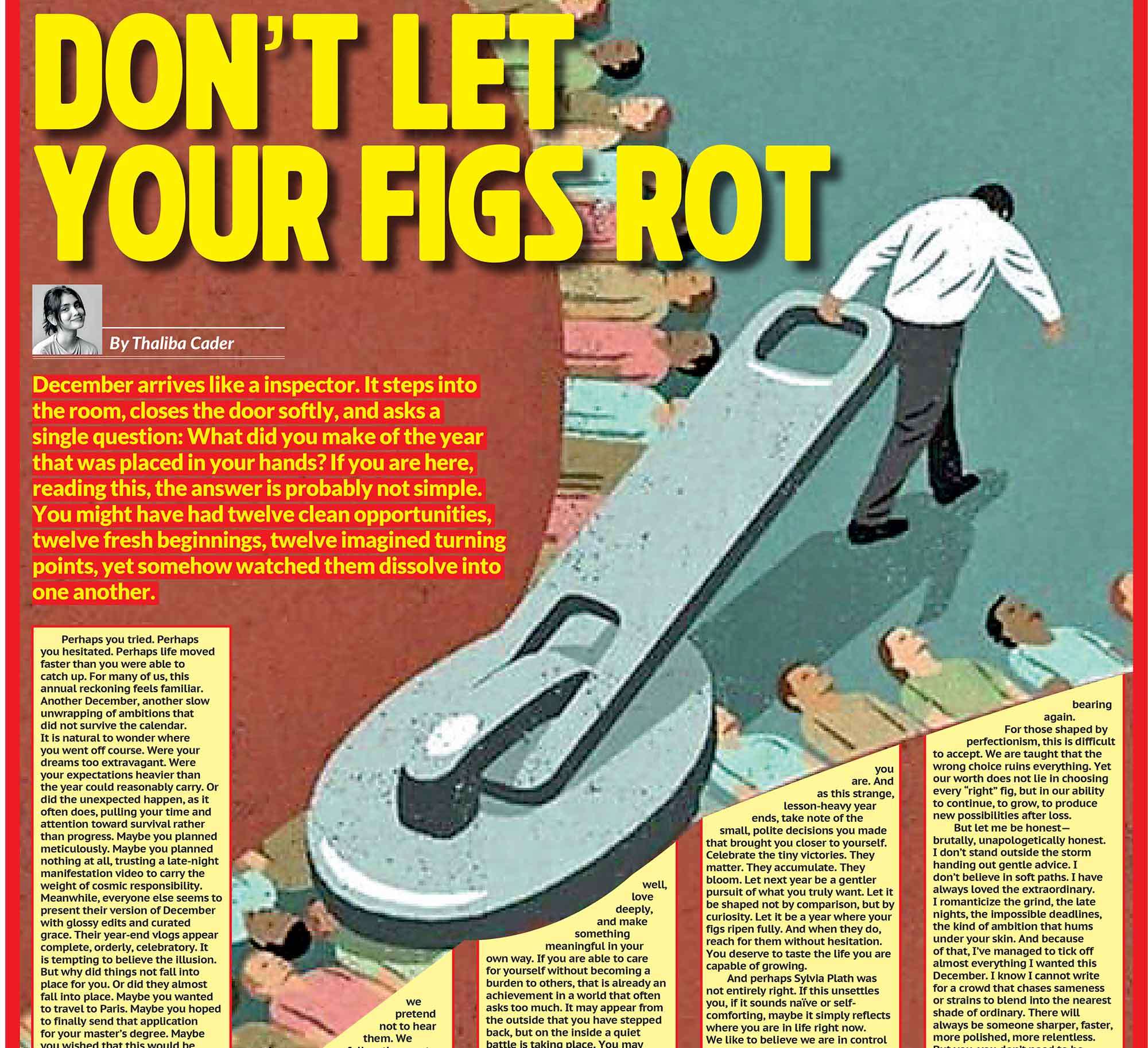

The Psychological Loop of More

Overconsumption is not just economic; it is emotional. Fashion marketing has mastered the art of manufacturing dissatisfaction. Each new drop subtly suggests that what you own is outdated. That last season’s colour is no longer relevant. That reinvention requires purchase. This constant cycle creates a hollow relationship with clothing. Garments arrive with excitement and leave with indifference. There is no time to build attachment, memory, or care. When clothes become disposable, so does meaning. And this is perhaps the quietest loss of all.

The Global South Bears the Weight

While fashion weeks, trend forecasts, and glossy campaigns dominate global narratives, the afterlife of clothing often ends far from these stages. Large volumes of discarded clothing from the Global North are shipped to countries in Africa and Asia under the label of “donations” or “second-hand trade.” Much of it is unusable, synthetic, damaged, or unsellable. It floods local markets, undermines local textile economies, and eventually ends up in open dumps or waterways. What began as excess in one part of the world becomes pollution in another. This is not circularity. It is displacement.

Conscious Consumerism Is Not About Perfection

The answer to overconsumption is not moral superiority or rigid rules. It is awareness and restraint. Conscious consumerism does not demand that everyone dress minimally or abandon fashion altogether. It asks better questions:

- Do I need this, or do I want novelty?

- Will I wear this at least thirty times?

- Can this be repaired?

- Do I know who made this?

Small shifts, multiplied across millions, matter more than performative sustainability slogans. Buying less is not anti-fashion. It is pro-future.

Relearning Relationship Over Replacement

Relearning Relationship Over Replacement

There is a quiet return happening, away from excess and toward intimacy with objects. People are rediscovering tailoring, mending, vintage, handcraft, and small-batch production. Not as trends, but as values. This shift is not loud. It does not rely on logos. It relies on touch, story, and intention. A garment that carries provenance, who made it, where, and how, naturally invites care. You hesitate before discarding it. You repair it. You remember moments lived in it. This is how clothing regains dignity. The fashion industry does not need more garments. It needs better decisions. Designers must design for longevity, not just impact. Brands must produce for demand, not speculation. Consumers must relearn that restraint is not deprivation; it is discernment. When 150 billion garments chase 8 billion humans, something is deeply misaligned. Fashion was never meant to be this loud, this fast, or this wasteful. Beyond the seams of our clothes lie systems, lives, and landscapes. The question is no longer whether overconsumption exists. The question is whether we are ready to participate less, and care more!