Introduction: A Relic That Could Crown or Destroy a King

Introduction: A Relic That Could Crown or Destroy a King

In medieval Sri Lanka, kings were not made merely by birth, conquest, or coronation. They were made by a small fragment of calcified bone. The Tooth Relic of the Buddha, housed today in Kandy but once carried across the island in war and ceremony, was the ultimate symbol of sovereignty. To possess it was to be king. To lose it was to fall from grace, power, and legitimacy. No kingdom in Asia linked divine relic and royal authority as tightly as Sri Lanka did. And no period reveals this more vividly than the centuries between Polonnaruwa and Dambadeniya, when the island convulsed under foreign invasion, internal treason, and dynastic collapse. Across these upheavals, one constant remained: the throne belonged to whoever commanded the Relic.

I. The Origins of a Political Theology

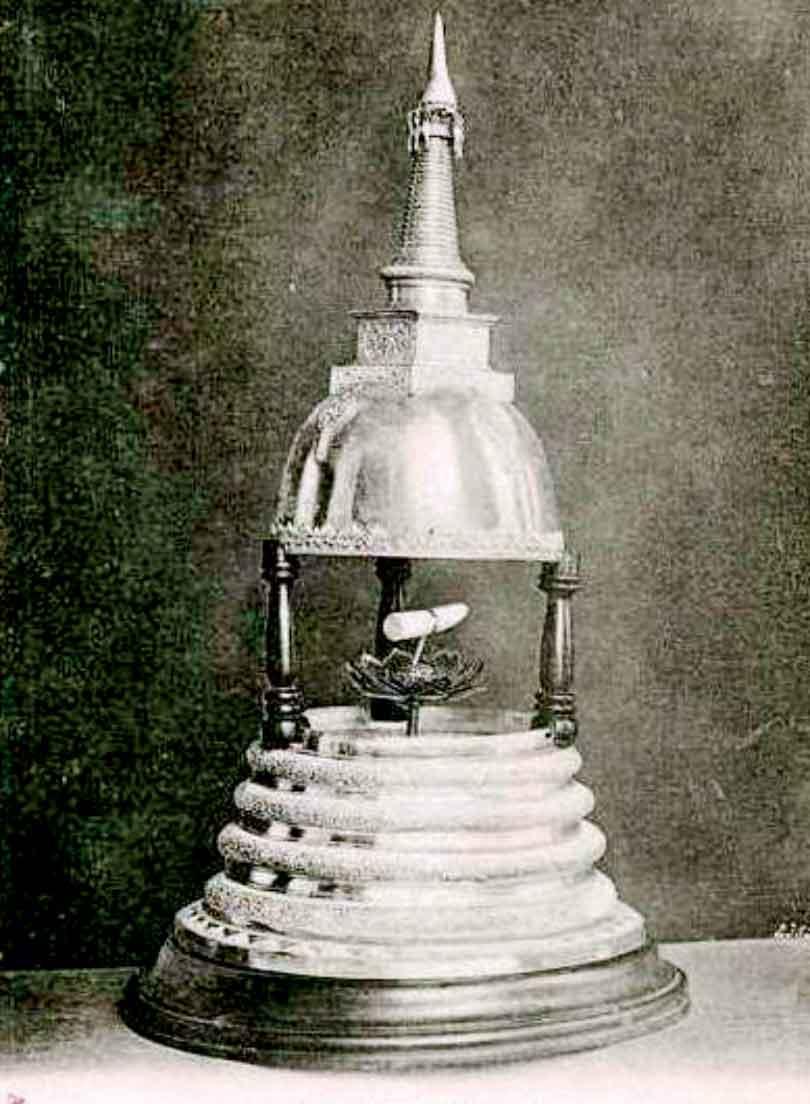

The Dāṭhāvaṃsa, a 13th-century Sinhala poem, recounts the Tooth Relic’s arrival in the 4th century CE, carried from Kalinga by the princess Hemamālā and Prince Danta to the court of King Kittisirimegha. From the start, the Relic was not merely an object of devotion. It was public, visible, and ceremonial. It was processed before crowds, displayed before pilgrims, and guarded as a royal emblem. This made it fundamentally different from Sri Lanka’s other great relic, the Bodhi Tree, which symbolized continuity and enlightenment rather than executive authority.

The Tooth Relic’s power lay in representation. It embodied the Buddha as sovereign. Not just teacher. Not just saint. Ruler. From this theological foundation grew a political doctrine:

- Only a king who possessed the Tooth was the rightful protector of the dharma.

- The kingdom thus had a built-in mechanism of legitimacy, and a mechanism of crisis. Any king could be challenged by anyone who claimed the Relic.

II. Polonnaruwa: The Relic as State Standard

In Polonnaruwa, this doctrine crystallized.

Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186) understood that the Relic was the anchor of his authority.

His reforms of the sangha, his campaigns abroad, and his construction of the Parakrama Samudra were all framed as acts performed under the guardianship of the Tooth. When he processed the Relic through the city, he staged kingship not as hereditary privilege but as cosmic duty.

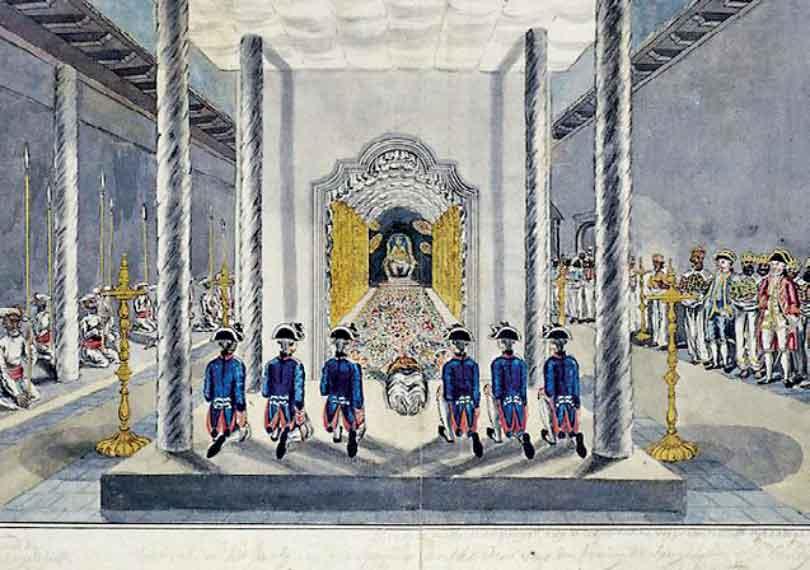

The Relic was carried before armies during consecration rituals. Festivals such as the Dalada Perahera became not merely religious events but demonstrations of political order. The king led. The monks sanctioned. The people witnessed.

The Relic functioned as the republic of the island’s memory. It made the king visible, verifiable, and accountable to something greater than himself. Yet this power also made the kingdom more vulnerable, for the Relic could be seized, hidden, stolen, or used to anoint rivals.

III. The Crisis of the Relic Under Invasion

The invasion of Magha of Kalinga in 1215 plunged Polonnaruwa into chaos. Magha, supported by Tamil and Kerala mercenaries, occupied the city and desecrated temples. Chronicles describe devastation, flight, and famine. But the real crisis was not architectural or agricultural. It was symbolic. As long as Magha held the capital, he could claim the throne. But he did not hold the Tooth. The monks anticipated this. In one of the most remarkable acts of political resistance in Sri Lankan history, they smuggled the Relic away from the city. It was hidden in monasteries in Rohana, guarded by the kingdom’s remaining loyalist aristocracy. The Relic went underground. This was not simply the preservation of a sacred object. It was the withdrawal of legitimacy from a king.

- Magha ruled the land.

- But he did not rule the kingdom.

IV. Queen Sugala Devi: The Woman Who Went to War for the Relic

The most extraordinary chapter in this story belongs to Sugala Devi, queen of Ruhuna. When the Relic was spirited away to the south, Sugala became its defender. Chronicles describe her as bold and unyielding, rallying clan militias and resisting royal and foreign armies alike. She did not merely shelter the Relic. She fought for it. For nearly two decades she waged war against the northern kings, refusing to surrender the symbol that made them kings at all.

- Her rebellion failed.

- But her role is unmistakable.

- She proved that the king did not crown the Relic.

- The Relic crowned the king.

Few women in premodern South Asia played such direct roles in statecraft. Yet in Sri Lanka, the intertwining of relic and sovereignty made such interventions not only possible but inevitable.

V. Dambadeniya: The Reforging of Kingship

Out of this fracture came Vijayabāhu III (r. 1232–1236), ruling from the hill capital of Dambadeniya. He did not inherit Polonnaruwa. He did not inherit its palace, its irrigation network, or its imperial cosmopolitanism.

- He inherited the Tooth.

- He built a throne around it.

When his son Parākramabāhu II (r. 1236–1270) held public Relic processions, he was not reviving old traditions.

He was reasserting a political theology:

- The kingdom had moved. But kingship had not.

- This mattered not only inside Sri Lanka but abroad. In correspondence with Burmese and Pandyan rulers, ambassadors emphasized the possession of the Relic as evidence of unbroken sovereignty. Even in exile, the Sri Lankan kingship remained intact because the Relic remained intact.

- The map of power had changed. But the grammar of legitimacy had not.

VI. The Relic as Constitution

By the 13th century, the Tooth Relic had effectively become the constitution of the island. It determined succession. It stabilized crises. It preserved continuity across war and displacement. Unlike European coronation regalia, which could be replaced or replicated, the Tooth was singular. Its uniqueness created a monopoly on legitimacy. But this also meant that the kingdom was never truly imperial. It could not expand indefinitely, because sovereignty could not multiply. There was only one throne because there was only one Relic.

This is the paradox of Sri Lankan kingship:

- The Relic made sovereignty durable.

- But it also made sovereignty fragile.

- A kingdom could move capitals.

- It could lose cities.

- It could flee into forests.

- But it could not lose the Relic.

VII. What This Means Today

The Tooth Relic is no longer a political instrument. But its legacy continues. Kingship in Sri Lanka was never simply secular or coercive. It was ritual, ethical, and symbolic. Authority required performance, not just force. It required public recognition, not only dynastic succession.

Modern Sri Lankan political culture still bears traces of this heritage:

- The expectation that leaders justify themselves through moral language.

- The public performance of legitimacy through spectacle.

- The belief that the nation is anchored in something sacred and collective, not merely administrative or legal.

- The Tooth Relic is no longer carried into battle.

- But it still presides over the imagination of sovereignty.

Conclusion: A Kingdom Made of Memory

The story of the Tooth Relic is not a story of religion alone. It is a story of statecraft. A relic became a throne. A monastery became a palace. A procession became a claim to sovereignty. And in the end, a kingdom survived because its symbol survived. The kings who ruled Sri Lanka came and went. Their capitals rose and fell. Their armies won and were defeated.

- But the Relic endured.

- The Tooth crowned them.

- And the Tooth outlived them.