Inside Prague’s Forum Media 25: Where the Battle for Truth Begins

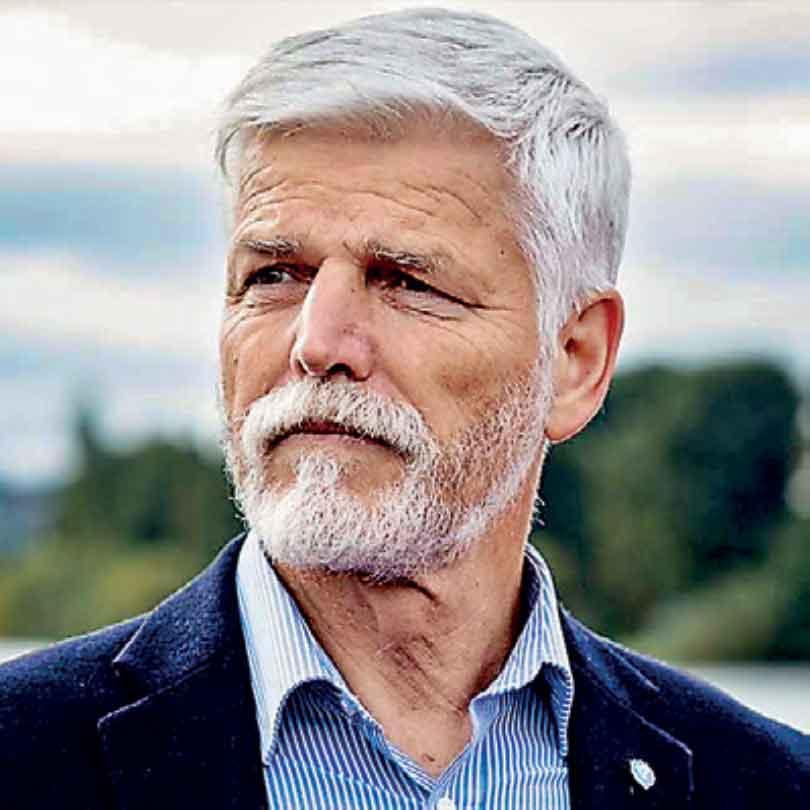

President of the Czech Republic, Petr Pavel

The last week of November, Prague, a city whose beauty is matched only by its sense of history played host to the 25th anniversary of the Foreign Media Forum, one of Europe’s most respected gatherings for strategic communications, political messaging, and media scholarship. It was my first time attending this long-running conference, and indeed my first time in the Czech capital. Yet from the moment I arrived, it was immediately clear why this event has endured for a quarter of a century: substance, seriousness, and the kind of intellectual rigour that is increasingly scarce in global discussions about media and public relations.

The Forum opened not with spectacle, but with diplomacy. On the evening before the conference, speakers were hosted at an intimate dinner by His Excellency Matt Field OBE, the British Ambassador to the Czech Republic. In a world where diplomacy is often caricatured as distant or opaque, the evening’s conversation served as a reminder of its evolving relevance. Ambassador Field spoke about the need for modern diplomats to be understood by wider audiences, not as remote figures but as practitioners of public service whose work demands transparency, clarity and engagement.

One initiative he described struck a particular chord: “Ambassador for a Day,” a competition that invites young people to step into the shoes of a diplomat, with the entire experience documented on social media. It is, in many ways, the antithesis of the dusty stereotypes of foreign service. Instead, it opens the door to a younger generation who instinctively understand narrative, community and digital identity, the pillars of contemporary communication. In an age when institutions face declining trust, such efforts to demystify public roles should be taken seriously by policymakers everywhere.

Yet if the dinner laid the groundwork, the conference itself delivered a substantive examination of the challenges and possibilities facing modern communications. At the heart of it was a speech by the President of the Czech Republic, Petr Pavel, who attended in person, a gesture of commitment that itself said much about the national value placed on media literacy and public communication.

President Pavel spoke powerfully about the importance of strengthening media literacy across societies, emphasising that it is not merely a desirable competency but a democratic necessity. He warned that misinformation, a challenge felt acutely in Central Europe, as in the rest of the world, corrodes not only trust, but cohesion. He advocated greater collaboration between government, academia and industry to rebuild media capability, especially in the younger generation. It was notable that a head of state chose to attend a communications conference; rarer still that he spoke with such clarity about the role of information in shaping resilient democracies. His comments set the tone for the conference’s broader themes: cognitive drift, political persuasion, and the deepening role of artificial intelligence in communications.

The Cognitive Drift: A Warning for Professionals

One of the most arresting presentations came from scholars examining “cognitive drift,” the subtle but significant ways in which human cognition is changing under the influence of digital tools and, increasingly, AI.

Three concepts were particularly resonant:

- Cognitive Offloading: the extent to which we outsource memory and processing to technology.

- Illusion of Knowledge: when individuals remember the source of information but not its substance.

- Metacognitive Laziness: the tendency to forgo reflection and critical thinking when AI tools offer immediate, but shallow answers.

For those of us in public relations, this is not a theoretical concern. Communication professionals pride themselves on judgement, synthesis and nuanced understanding. Yet if these cognitive muscles atrophy, the consequences are profound: uniformity of output, poorer quality work, and an industry whose practitioners lose the very skills that define it. The researchers warned that over-reliance on AI can produce de-skilling within teams and a worrying homogenisation of communication products. Leaders, they cautioned, may find themselves increasingly responsible for plugging competence gaps, a trend visible in agencies globally. Their conclusion was both a caution and a call to arms: AI can elevate the profession, but only if practitioners remain vigilant about preserving independent, human critical thinking. It echoed a sentiment I have long held, that the golden age of PR is not threatened by technology, but by complacency.

Understanding Human Behaviour: Lessons from Political Communications

Few sessions were as compelling as those led by Lord Evans, whose deep experience in political campaigning has made him one of the United Kingdom’s most respected strategists. Drawing on decades of research, he broke down voter psychology into three broad behavioural archetypes: Safety First, Aspirational, and Socially Liberal. While these categories emerged from British data, their underlying principles resonate globally.

Safety First

This group seeks stability, clarity and order. They respond to strong leadership, moral frameworks, and messages anchored in economic security. They are often anxious about change and rely heavily on local networks.

Aspirational

Focused on progress, results and personal improvement. They respond to leadership that removes barriers, demonstrates competency and emphasises choice and economic opportunity. They are neither inherently conservative nor liberal; they are pragmatic.

Socially Liberal

Guided by transparency, fairness and ethical reasoning. They value diversity, intellectual debate, and global connectivity. They begin cultural trends rather than follow them.

Lord Evans argued that political communication is inherently Maslovian. In other words, it mirrors the hierarchy of human needs: safety at the base, aspiration in the middle, and self-expression at the top. Effective communicators understand not only what people think, but why they think it.

This is valuable far beyond electoral politics. For governments, corporates and NGOs, the lesson is clear: policy failures are often messaging failures rooted in a misreading of behavioural drivers. Too many institutions speak to audiences as they wish them to be, rather than as they are.

Principles of Persuasion: No Shortcuts in Communication

Lord Evans also articulated seven principles that underpin persuasive campaigns. They are deceptively simple but profoundly consequential:

- Campaigns are about changing behaviour.

- Understanding people is non-negotiable.

- Persuasive storytelling is the engine of behavioural change.

- Trust is the essential prerequisite of persuasion.

- Influence must be built, not assumed.

- The science of influence should inform every aspect of strategy.

- There are no shortcuts: communicators must work harder than their opponents.

These principles apply equally in politics, public relations and public diplomacy. They also speak directly to the current moment in global communications: a time defined not by message scarcity but message saturation. The battle is no longer to be heard; it is to be trusted, and to be chosen. Perhaps the most sobering slide he presented described politics as a battle of framing. Frames, he noted, are not simply linguistic devices; they are the organising structures through which societies interpret the world.

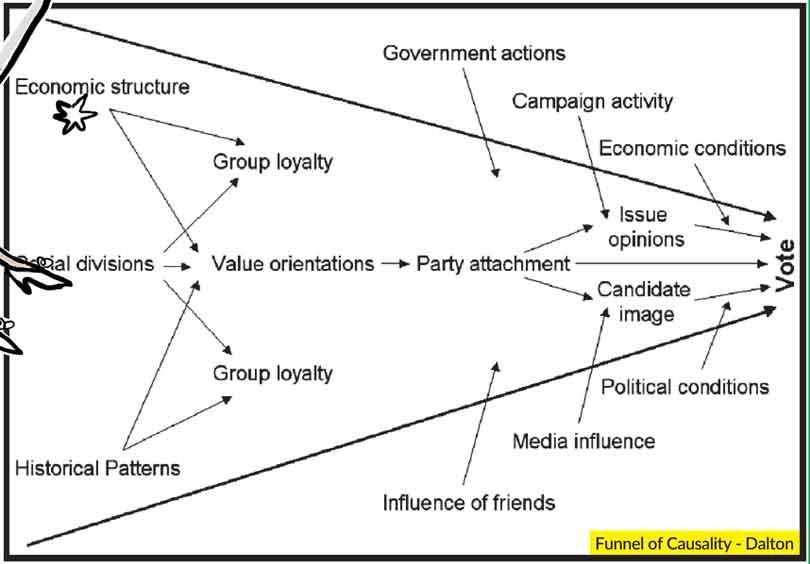

Maximising Influence Across the Funnel

Closing his keynote, Lord Evans invoked Dalton’s “funnel of causality”, a sophisticated diagram tracing how social structures, group loyalties, media influences and political conditions all converge to shape individual voting decisions. His point was direct: effective communication requires impact at every stage of that funnel. This has implications for governments and institutions worldwide. Influence is not built through isolated messages or campaigns. It is built through consistency, credibility and connection across every layer of a society’s informational ecosystem.

Why Prague Mattered

As I left the conference hall on the final day, I reflected on what made this event so valuable. It was not merely the calibre of the speakers, though they were exceptional, nor the impressive organisation by APRA and the wider Czech communications community. It was the reminder that communications, at its best, is not tactical but philosophical.

Three lessons stood out:

1. In-person engagement matters more than ever.

After years of virtual events, the energy, candour and intellectual exchange that occurred in Prague could not have been replicated online. Relationships are the bedrock of influence, and they are built face-to-face.

2. The industry is entering a phase of renewed confidence.

The mood was markedly different from two years ago, when the rise of AI generated fear about job losses and professional obsolescence. In Prague, optimism dominated. AI is now understood as a tool, powerful but not omnipotent and one that can elevate rather than undermine the profession. We may, indeed, be re-entering a golden era of strategic communications.

3. Communications is now central to democracy and diplomacy.

From President Pavel’s remarks on media literacy to Ambassador Field’s vision for accessible diplomacy, the message was clear: communication is not ancillary. It is foundational to societal resilience.

Many countries around the world stand at an inflection point. Economic recovery, political reform and national reconciliation are all contingent not only on policy choices but on the narratives that accompany them. The lessons from Prague are therefore deeply relevant to all of us.

We must invest in media literacy, not as a luxury but as a safeguard. We must understand behavioural drivers rather than assume them. We must build trust deliberately, consistently and transparently. And we must resist the cognitive drift that threatens to dilute the very capabilities society depends on. Prague reminded me that communications, when practised with integrity and intelligence, is a public good. It strengthens society, empowers citizens and bridges the gap between institutions and the people they serve. It is my hope that we embrace these lessons, not just for the sake of our profession, but for the future.

-----------------------

About The Writer

Farzana Baduel, President-elect (2026) of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations and CEO and Co-founder of Curzon PR (UK), is a leading specialist in global strategic communications. She advises entrepreneurs at Oxford’s Said Business School, co-founded the Asian Communications Network (UK), and serves on the boards of the Halo Trust, and Soho Theatre. Recognised on the PRWeek Power List and Provoke Media’s Innovator 25, she also co-hosts the podcast, Stories and Strategies. Farzana champions diversity, social mobility, and the power of storytelling to connect worlds.