There is a particular kind of vertigo that sets in when the people we were taught to trust turn out to have been unworthy of it all along. The release of more than three million pages of Epstein-related files by the United States Department of Justice has produced exactly that sensation, not just in America, but with seismic force across the Atlantic, where it has engulfed the British government, rattled the monarchy, and triggered the most serious political crisis the United Kingdom has faced in a generation.

There is a particular kind of vertigo that sets in when the people we were taught to trust turn out to have been unworthy of it all along. The release of more than three million pages of Epstein-related files by the United States Department of Justice has produced exactly that sensation, not just in America, but with seismic force across the Atlantic, where it has engulfed the British government, rattled the monarchy, and triggered the most serious political crisis the United Kingdom has faced in a generation.

At the centre of the storm is Peter Mandelson, the architect of New Labour and one of the most consequential political operators in modern British history. Mandelson was appointed by Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, as Britain’s ambassador to the United States in late 2024, a role he held for barely seven months before being sacked in September 2025, when the first tranche of files revealed the depth of his relationship with the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. In early February 2026, a further release exposed what appears to be the leaking of market-sensitive government information to Epstein while Mandelson served as business secretary during the 2008 financial crisis. He resigned from the Labour Party, stepped down from the House of Lords, and is now the subject of a criminal investigation by the Metropolitan Police for potential misconduct in public office. Officers searched his London home on the 7th of February.

The fallout has been extraordinary. Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, resigned on the 9th of February, taking responsibility for advising the prime minister to make the appointment. Starmer himself has apologised twice to Epstein’s victims, saying he had believed Mandelson’s “lies” about the nature of the relationship. Senior Labour figures, including the Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar, have called on Prime Minister Keir Starmer to step down. Meanwhile, renewed scrutiny of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, the former Duke of York, Prince Andrew, already stripped of his royal titles, has reopened painful questions about accountability at the highest levels of national life. These are not abstract political dramas. They land with force because they involve people whose names and offices once commanded automatic deference. For many ordinary citizens, the shock lies not only in the substance of what has been revealed but in the implicit question it raises: how did we ever invest so much trust in figures whose positions were supposed to embody responsibility? And it is that question, what trust actually looks like, who deserves it, and how it is built, that I have been thinking about since a conversation in Colombo in December 2025, with a leader who offers the most striking counterpoint imaginable.

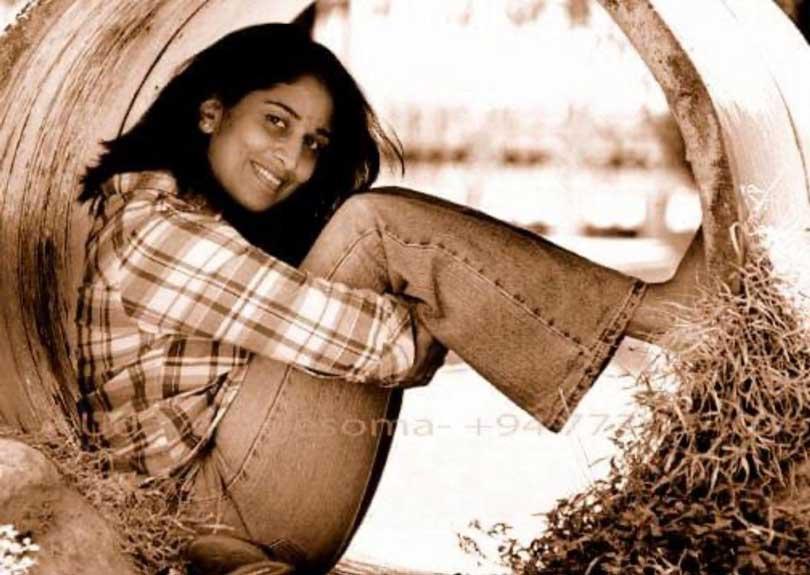

Varuni Amunugama Fernando co-founded the advertising agency Triad in 1993 while still a second year law student at the University of Colombo. Together with her business partner Dilith Jayaweera, she began with a team of just three people and a clear conviction that Sri Lanka’s communications industry did not need to be dominated by multinational networks. They believed a home-grown agency could compete at the highest level while remaining deeply rooted in local insight and culture. More than three decades later, that belief has evolved into one of the most diversified communications groups in the country. What started as a small advertising outfit has grown into a wide-ranging portfolio spanning integrated communications, media production, photography and creative services. Beyond the communications sphere, the group has expanded into significant corporate investments, including positions in George Steuart & Co., Sri Lanka’s oldest mercantile establishment, and the Derana Media Network, one of the nation’s leading television and radio platforms. Its interests now extend further into hospitality, real estate and publishing, reflecting a long-term strategy built on diversification and influence. Yet what distinguishes Varuni most is not the scale or range of her business interests, impressive as they are. It is the manner in which she leads. Her leadership style is not defined by distance or hierarchy, but by presence and personal engagement.

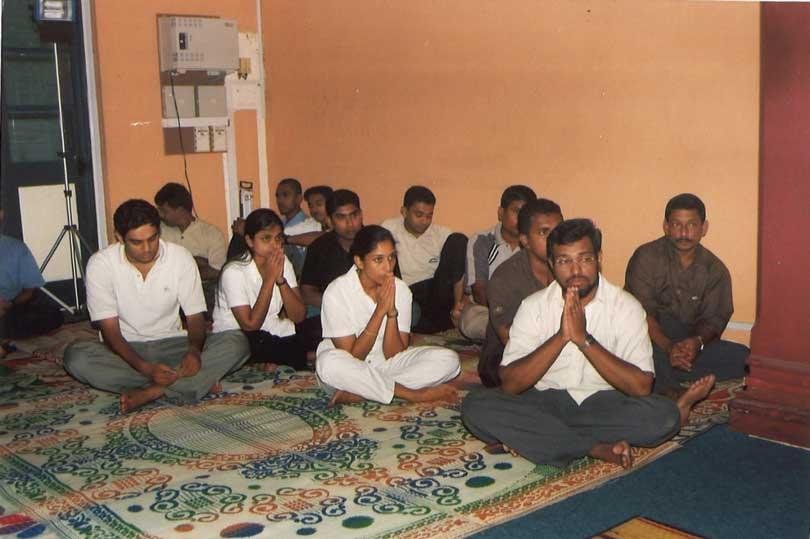

When I met her one evening for dinner at The Blue Orbit by Citrus inside the iconic Lotus Tower in Colombo, I was immediately struck by the way she interacted with everyone in the room. From senior executives to junior staff, she gave each person her full attention. There was a warmth to her manner that felt entirely genuine. Nothing appeared staged or performative. She later explained that this approach is instinctive. People matter to her at a fundamental level. She chooses to move first toward positive engagement not because it is fashionable or strategically advantageous, but because she sees it as foundational to effective leadership.

Her philosophy of team building is anchored in a concept she calls API, a Sinhala word meaning us. It is more than a slogan. It is a framework designed to make her organisations feel like extended families bound by shared purpose, empathy and mutual accountability rather than rigid hierarchy alone. She recruits for attitude before technical skill, believing that competence can be developed but character must be present from the start. Within her companies, individuals are often stretched beyond their comfort zones and placed in demanding situations. Yet they are not left unsupported. They are heard, guided and empowered to grow. In a global climate where leadership is frequently criticised for detachment and opacity, her model emphasises proximity, dialogue and visible responsibility. At its core lies a simple but powerful principle that kindness in leadership is not weakness. It is discipline, consistency and strength expressed with humanity.

I have spent my career in strategic communications, advising governments, institutions and corporate leaders on how trust is built and how it is lost. What the Epstein scandal has exposed is not merely a catalogue of individual moral failures. It is a structural crisis in the way power operates, the assumption that proximity to influence, the accumulation of titles and networks, the cultivation of mystique and opacity, are themselves markers of leadership. They are not.

They are markers of access. And as we are learning, often painfully, access without ethics is hollow. Prestige without principle collapses under its own contradictions. If these revelations teach us anything, it should be that we must fundamentally recalibrate what we admire in leaders. Not the spectacle of excess and secrecy, but the quiet discipline of integrity. Not the glare of privilege, but the warmth of genuine, inclusive humanity.

Kindness is not a public relations strategy, nor is it a decorative trait added to leadership for appearance. It is not an accessory designed to soften an otherwise hard-edged persona. True kindness is a measure of character. It reflects a belief that people possess inherent worth beyond their utility, performance or influence. It says clearly and without qualification: I value you not for what you can deliver, but because your dignity is non-negotiable. This distinction is especially significant in Sri Lanka at a time when the nation continues to rebuild after years of deep economic strain and political upheaval. Institutions have been tested. Public confidence has been shaken. In such an environment, leadership cannot rely solely on authority, charisma or displays of strength. What is required is something more enduring and more demanding.

The leaders who will shape the country’s next chapter are unlikely to be those who cultivate an image of invincibility. Instead, they will be those who understand that trust is built quietly and consistently through everyday actions. Trust is formed in boardrooms where transparency replaces secrecy, in communities where listening replaces rhetoric, and within institutions where accountability is embraced rather than avoided. In a society fatigued by disappointment and wary of broken promises, kindness becomes more than a personal virtue. It becomes a stabilising force. It fosters loyalty, encourages collaboration and restores confidence in shared systems. In a world that has grown sceptical of power, the deliberate practice of humane leadership may be the most meaningful reform still available to us.

----------------------

About The Writer

Farzana Baduel, President of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations and CEO and Co-founder of Curzon PR (UK) is a leading specialist in global strategic communications. She advises entrepreneurs at Oxford’s Said Business School, co-founded the Asian Communications Network (UK), and serves on the boards of the Halo Trust, and Soho Theatre. Recognised on the PRWeek Power List and Provoke Media’s Innovator 25, she also co-hosts the podcast, Stories and Strategies. Farzana champions diversity, social mobility, and the power of storytelling to connect worlds.