In Conversation with Dr. Sara Nasserzadeh

On Sex Education in Sri Lanka & Why Protection Isn’t “Western” | PART 2 OF 2

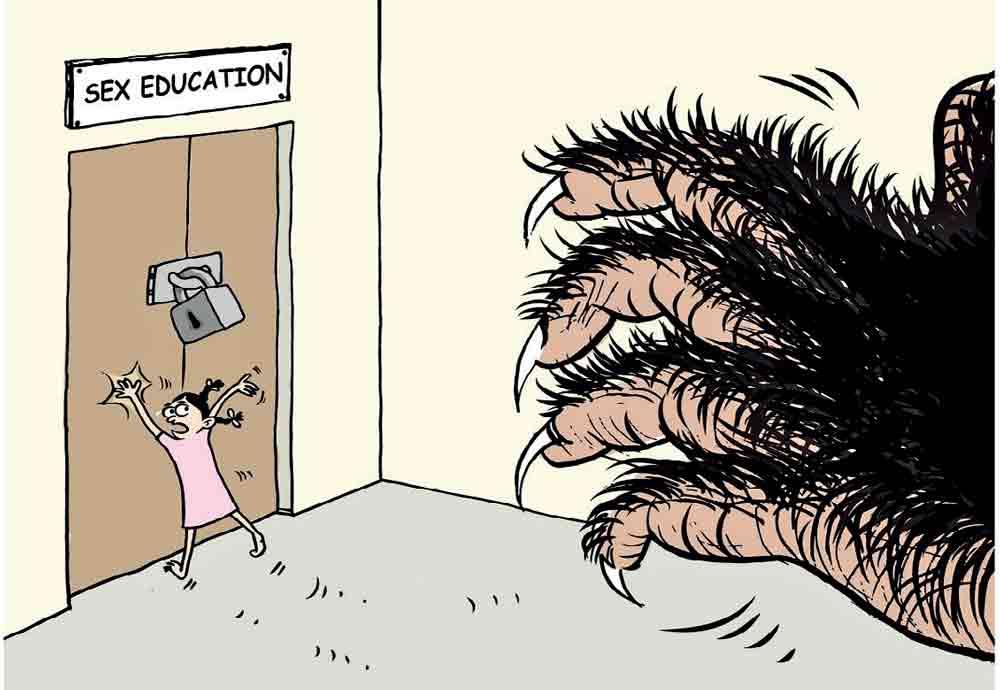

In Part 1, we saw the evidence: comprehensive sexuality education protects children. But what happens when parents stay silent? When young people grow up without language for their bodies or boundaries? Dr. Nasserzadeh takes us from theory to lived reality in part 2.

Writer’s Note: This interview provides research-based perspectives on sexuality education. It does not advocate for any single curriculum, but seeks to support informed, culturally aware dialogue.

Q 67% of Sri Lankan parents lack adequate knowledge about child sexual abuse. What are the consequences when parents stay silent? And what would you say directly to Sri Lankan parents?

First, I would like to say to Sri Lankan parents: your discomfort is understandable, and you are not alone. Many parents around the world were themselves raised in silence and are now being asked to do something they never saw modelled. This is a heavy burden.

When parents stay silent, children still receive messages about sexuality, they simply receive them from less dependable sources. Peers, pornography, advertising, and social media step into the gap. Psychologically, children may conclude that their questions are shameful, that their bodies are dangerous, or that adults cannot be trusted with their vulnerability. This can increase the risk of secrecy if abuse occurs, because the child fears they will be blamed, disbelieved, or punished. Even if you cannot take actions (because the abuser is a person of power, a relative that you cannot confront, etc.) at least just listen and validate the child so they don’t internalise the shame. You might not believe this but as a clinician I have to tell you that such an incident can alter the person’s whole trajectory of life. Many parents don’t open these conversations because they are afraid of not being able to handle them or have the right answer, just holding the space and listening to the child goes a long way.

In adulthood, I often see the echoes of this silence: difficulty expressing desire or discomfort, confusion between love and control, and a tendency either to avoid conflict entirely or to erupt when tension has built up for too long.

To parents who feel unprepared, I would say: you do not have to become an expert overnight. Your children do not need perfect lectures; they need approachable, trustworthy adults. It is perfectly acceptable to say, “No one talked to me about this when I was your age, but I want us to do better. Let us learn together.” Taking a small step such as correctly naming body parts, explaining the difference between safe and unsafe touch, or telling your child that they can always come to you if something feels wrong can already shift the atmosphere in a family.

Q If you were advising Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Education, what would a culturally adapted framework look like?

I would begin by affirming that any framework must be clearly rooted in Sri Lanka’s own ethical traditions. Buddhist principles such as non-harm, compassion, mindfulness and right action provide an excellent moral foundation for protecting children and promoting healthy relationships. Similar values exist in the island’s Hindu, Muslim and Christian communities. Comprehensive sexuality education should be presented not as a foreign ideology, but as one practical expression of these shared commitments. This is only possible if informed scholars and religious leaders come together to design programs. We have done this many times across the world and it is possible.

In terms of non-negotiables, the evidence suggests several core elements: age-appropriate, accurate information about bodies, puberty and reproduction; early teaching about bodily autonomy, safe and unsafe touch, and how to seek help; progressive development of emotional literacy including managing peer pressure; clear education about consent, boundaries and respect; and for older adolescents, information about contraception, sexually transmitted infections, digital risks, and accessing services, always framed within values of responsibility and care.

Within these pillars there is significant room for cultural flexibility. Countries have successfully adapted curricula by using local stories and proverbs, involving religious leaders in reviewing materials, offering single-sex classes for sensitive topics, and creating parallel programs for parents.

The key is transparency and participation. When communities are invited into the design process, when they see that the goal is protection and flourishing rather than moral dismantling, the conversation becomes less about “for or against sexuality education” and more about “what kind of education best serves our children, our values and the future of our country.”

Q In Sri Lanka, 1,500+ girl children were raped in 2023, many in “romantic affairs.” What does it mean when young people don’t have the language for consent?

When young people do not have language for consent, they are left to interpret very complex situations with very simple tools. They may equate love with endurance, attention with entitlement, or silence with agreement. In that context, a so-called “romantic affair” can easily mask profound power imbalances, coercion, or exploitation.

Consent is not only about saying “yes” or “no” to sexual contact. It is a lifelong relational skill that begins in early childhood. When a child is allowed to say, “I do not want to be tickled right now,” and the adult respects that, the child learns that their body and feelings matter. When a teenager is taught that they can change their mind, that they can ask questions, and that pressure or threats are never signs of love, they are more likely to recognise unsafe situations and seek help.

Research shows that programs which include communication and negotiation skills can increase young people’s ability to refuse unwanted sex, to seek protection, and to support peers who disclose abuse. Importantly, these skills can be taught without any explicit sexual content in younger age groups. Lessons about sharing toys, respecting personal space, listening when someone says “stop” all build the same neural pathways that later support healthy sexual consent. Teaching consent early is an act of safeguarding, not of permissiveness. It gives children a vocabulary to describe what is happening to them, and it sends a clear social message: your body is not available on demand, even (and specially) in the name of love.

Q How does the absence of sex education manifest as dysfunction or trauma in adulthood?

In many contexts where sexuality is taboo, I meet couples who arrive in therapy not because they rejected cultural values, but because they tried very hard to follow them and were simply not given enough information or skills to make that path safe or workable.

One pattern is unconsummated marriages. A couple may marry with little understanding of anatomy, arousal, or the fact that intercourse should not be “extremely painful”. The first attempts are frightening or traumatic, and over time avoidance, shame and blame take root. Conditions such as vaginismus, the involuntary tightening of pelvic muscles that makes penetration painful or impossible, can develop or be reinforced in this climate of fear. With appropriate education beforehand, many of these situations could be prevented or at least recognised much earlier.

Another pattern is people who have experienced abuse or coercion but did not have the language to name it as such. They may interpret their history as personal failure or impurity rather than as a violation of their rights. This can lead to chronic anxiety, depression, difficulty trusting partners, or difficulty feeling desire without also feeling fear. If children and adolescents learn about consent, power dynamics and help-seeking, some of these experiences can be prevented.

Clinicians in Sri Lanka have reported concrete cases where lack of sexuality education contributed to repeated teenage pregnancies and unsafe abortions. These are not abstract moral debates; they are lived realities with lifelong consequences.

Q What would you want Sri Lankan leaders to understand about the long-term benefits, especially when faced with backlash?

I personally don’t like to call anyone “opposition” because this immediately raises everyone’s guards. I would first express respect for the courage it takes to even open this conversation. When leaders move ahead with comprehensive sexuality education in a climate where there are misalignments, they are often criticised from many sides. It is important to keep in view not only the uproar of the present, but also the quiet benefits that will accumulate over time.

The long-term benefits are not limited to sexual health indicators. Comprehensive, culturally adapted sexuality education is associated with reductions in child sexual abuse and exploitation, fewer unintended adolescent pregnancies, and greater use of protective behaviours. It also supports broader goals: improved mental health, greater gender equity which will lead to societal and economic growth, more stable relationships, and increased capacity for compassion and non-violent conflict resolution.

In societies that have invested consistently in such education, we see adults who are better able to negotiate marital expectations, to parent with openness rather than fear, and to change harmful norms without feeling that they are betraying their culture. Comprehensive sexuality education can become one of the quiet infrastructures of peace: it teaches people how to live with their own bodies and with one another in ways that reduce harm.

For Sri Lanka, the decision is not whether to have sexuality education because young people are already being educated daily by the internet, peers and popular culture. The decision is whether that education will be accurate, values-aligned and protective, or whether it will be left entirely to chance. There may be backlash in the short term, but in a generation’s time, the benefits will be visible in healthier families, safer children, and citizens better equipped to build relationships worthy of the values Sri Lanka holds dear.

Conclusion

This is not an ideological battle. It’s a public health crisis masked as a cultural debate.

The question is whether Sri Lanka will design its own version, rooted in its own values or continue to outsource education to pornography and peers.

Every conservative society that has done this work found a way. They didn’t abandon their values. They applied them. They built their own models. They listened to fears and designed solutions together.

The backlash is loud now. But in a generation: fewer abused children, healthier relationships, adults who can name what they need and respect what others don’t want.

Sri Lanka’s children are already learning. The only question is: from whom?

About Dr. Sara Nasserzadeh

Dr. Sara Nasserzadeh, PhD is a social psychologist, psychosexual therapist, and senior intercultural advisor. She created the BBC Whispers program and is author of Love by Design and co-developer of the Sexuality Education Wheel of Context. She has worked in 41 countries advising governments, NGOs, and the UN.

Learn more: www.Sara-Nasserzadeh.com