A Tuk Ride Should Cost More Than a Cab. Why Not?

There is something quietly absurd about a tuk costing more than a car. Not absurd in a numerical sense, but in what it signals. A tuk is loud, imperfect, open to dust and rain, driven by someone who may tell you unsolicited truths about politics, weather, or the general state of the nation. A car is sealed. Air-conditioned. Silent. Its driver is polite enough to disappear into the function of the ride. When the tuk begins to demand more than the car, something in the city’s logic shifts.

I did not notice this immediately. Only later did I realize how rarely we interrogate the ordinary until it begins to slip away. The tuk has never been about efficiency. It has been about proximity. To the road. To noise. To people. It is the city breathing without apology. Choosing it has never been rational. It is relational. You choose it the way you choose familiarity over comfort, experience over insulation. But this is not really about transport. I would often rather walk.

It is about how we assign value to what is accessible. In cities constantly becoming, where cranes replace trees and speed is mistaken for progress, abundance is treated as a flaw. What is everywhere must be unimportant. What is easy must be temporary. And so we rush to discard what feels too close, too common, too honest. We do this not only with objects, but with feelings. Sadness, for instance, is treated like poor infrastructure. Something to be fixed, rerouted, eliminated. We build careful exits from it. We plan to outgrow it. When it finally loosens its grip, we rename the period resilience, productivity, or blessing. Rarely do we ask what it taught us. Rarely do we ask what was lost when we left it behind. Yet sadness is not a malfunction. It is a register of depth. It is how the body records meaning. In a country where survival itself has been intimate, political, economic, emotional, sadness has never been an intruder. It has sat beside us on pavements, under flickering streetlights, inside homes that learned to live with less. From it, art has always emerged. Sadness writes poems. It sends unlikely people like finance guys home at night to sit quietly with a feeling they cannot justify and a sentence they did not plan to write.

This is why some things should be expensive. Not because they are rare, but because they carry weight. Because they slow us down. Because they refuse to be bypassed. Sadness should cost us something. And it is not only an autoimmune disease. Not money, but presence. Time. What we rush past in the name of development often holds our most honest reflections. What we try hardest to escape is often what makes us human. What is a city without feeling? What is land without memory? What is the Earth without art? Just matter. Just a rock.

Writers understand this instinctively, even when they pretend not to. Writing has never belonged to speed. Donna Tartt wrote from her bathtub. Maya Angelou converted hotel rooms into temporary sanctuaries. Countless women prick their fingers on pens half-asleep at bedside tables. Writing asks for slowness, discomfort, a willingness to sit with what does not resolve quickly. Perhaps most people have it just at their step. And yet we panic when it takes time. We wonder if we are cautious or simply afraid. We tell ourselves it should be easy. That words should move like limbs through water, clean and efficient, leaving neat patterns behind them. But writing is more like digestion than motion. It cannot be rushed without consequence. Digestion, after all, does not begin in the mouth. It begins in the mind, in how safe the body feels. In whether we are present. Saliva, stomach acid, bile, and enzymes are not mechanical reactions. They are responses to permission. To pleasure. To attention. When we are distracted, dissociated, rushing, digestion switches off. Blood flow retreats. Discomfort follows. Like they already know this blind date is not the right fit for you. But do we give it grace? Lord, we don’t.

Food is meant to be divine. Plants convert sunlight into leaves, roots, and fruit. Animals eat those plants and become vessels of that same solar energy. Then we eat both, absorbing that concentrated light into our own cells. But don’t we savor the meat more? Same with the car and the tuk. What we have flattened into rules and macros is, at its core, magic. Pleasure is not indulgent. It is functional. It signals safety. It tells the body it is allowed to receive. Writing works the same way. You cannot force it into productivity without losing its nourishment. You cannot digest meaning while mentally elsewhere. Slowness is not failure. It is the condition required for absorption. And life, all of its worth, is just the same. Tuk rides should be expensive. They give you the final broth of the island with humans, with the cons of messy hair, the driver’s personal trauma, and the occasional turn on that reserve fuel. But it adds up.

Perhaps this is why the tuk unsettles us when it costs more. It mirrors what we have been trying to escape. Exposure. Noise. Intimacy. It refuses the illusion of efficiency. It insists that presence has a price. Some things should not be cheapened by convenience. Some things should demand time, attention, and a little discomfort. Art. Sadness. Writing. Even a ride through the city with the windows open.

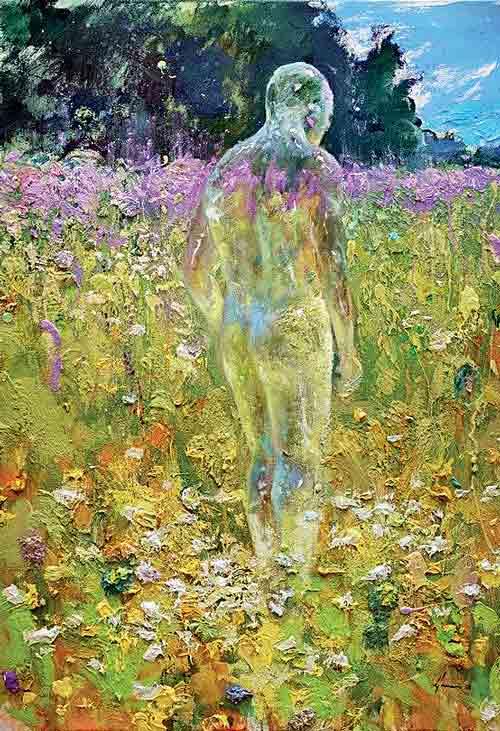

Because when everything becomes sealed, efficient, and fast, we arrive nowhere having felt nothing at all. And if you take nothing else from this, take this: the measure of a life is not what you get through it, but what gets through you. Every scratch, every jolt, every slow, messy, unpredictable moment is what colors your soul. Efficiency cannot teach you that. Only presence can. Only immersion. Only daring to ride the tuk, to feel the city, to sit with sadness, to taste without rushing, to live without sealing yourself off. Life is not to be managed. Life is to be inhabited. Fully.

It is a microcosm of life itself. If you demand that everything be smooth, predictable, and controlled, you will never know the texture of reality. You will miss the electricity in the air just after rain, the way light fractures through a torn awning, the subtle pulse of the upside down in your feet. You will have learned to move efficiently, yes, but you will have forgotten how to arrive. And perhaps this is the ultimate measure of any journey, of any moment, of any life: to be willing to be messy, to be slow, to be fully human in a world obsessed with speed and cleanliness. To let experience enter you, to let meaning infuse you, to sit with uncertainty and let it teach you. That is the luxury that matters. That is the tuk ride that costs more than the car. Because when you finally understand this, when you allow yourself to be present, you realize that the world has been offering its richest experiences all along. And all you have to do is be there to receive it.