The HALO Trust: Clearing Paths, Rebuilding Lives In Conversation | James Cowan, CEO and Farzana Baduel, Trustee.

Muhamalai Minefield Clearance

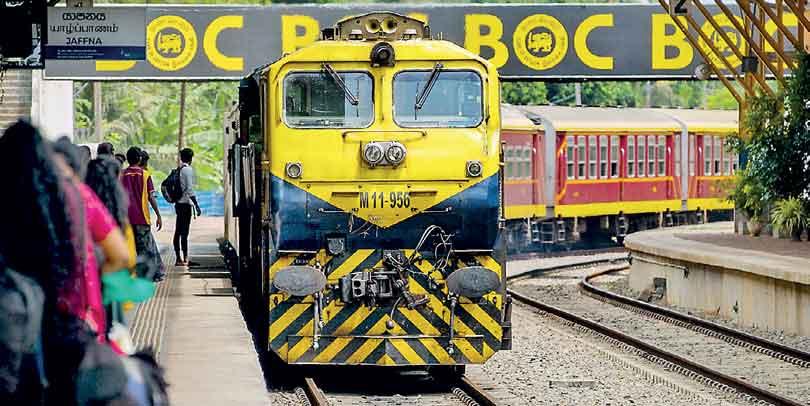

A train arriving, Jaffna Railway Station 2025

Jaffna Railway Station 2025

Mulhamalai mech clearance

Jaffna Railway Station 2002

Sivakumar Velu, Senior Boat Operator en route to an island minefield, Jaffna peninsula

James

Farzana

Success for HALO means seeing every country we serve declared mine free. It also means using new technology, including artificial intelligence, data mapping, and advanced detection, to make demining faster and safer.

The emotional toll is real. Our teams witness trauma and risk their lives daily. We provide psychological support, peer networks, and training. What sustains them is purpose, knowing they are saving lives and giving communities a future.

For nearly four decades, The HALO Trust has stood as a beacon of hope in the aftermath of war, restoring safety, dignity, and opportunity to communities once devastated by conflict. Founded in 1988, HALO began with a simple mission: to remove landmines that continue to kill and maim long after the guns fall silent. Today, that mission has evolved to meet shifting frontlines of danger, from Afghanistan to Ukraine, from Angola to Sri Lanka, wherever lives are disrupted by the remnants of war. Under the leadership of James Cowan, HALO’s chief executive since 2015, the organisation has expanded to operate in 32 territories, tackling not only landmines but also unexploded bombs, weapons stockpiles, and the complex realities of urban warfare. Joining him in conversation is Farzana Baduel, HALO trustee, communications strategist, and advocate for humanitarian impact. Together, they reflect on HALO’s journey, from restoring the soil of war-torn fields to rebuilding the foundations of human normality.

The HALO Trust has become synonymous with hope in post conflict regions. How would you describe HALO’s mission today, four decades since its founding?

James: HALO’s journey began in 1988, with a simple but urgent task: to rid the world of landmines. Designed for war, they make no distinction between soldier and civilian and remain as lethal decades after conflict has ended as the day they were laid. Clearing unexploded legacy remnants of war in places like Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Angola, and Zimbabwe remains at the heart of what we do, but our mission today has evolved to confront a wider spectrum of threats born of conflict itself. We increasingly operate amid live wars in countries like Ukraine and Gaza. Of the 32 territories in which we now work, half are still in conflict. HALO’s focus now spans from clearing landmines in remote agricultural fields to defusing bombs in urban settings and controlling the weapons that fuel instability. The past decade has been historic. We are witnessing the end of an era, the unravelling of the post 1989 order that sought to impose stability through rules and consensus, now replaced by a return to great power politics. HALO’s recent history has unfolded against this backdrop: the fall of Afghanistan, renewed unrest across the Middle East, and the brutal war in Ukraine. It is a very different world from the one I inherited in 2015, and it demands our presence more than ever. My vision is to make sure that HALO is central to people’s answer to the question of conflict.

From Afghanistan to Ukraine, and Sri Lanka to Angola, HALO operates in some of the world’s most challenging environments. What drives your continued commitment to these regions?

James: What drives me, and indeed everyone who works at HALO, is a profound sense of responsibility to those who live every day with the impact of conflict. These are not abstract crises. They are real places, with real people, whose lives are shaped by forces beyond their control. Whether in Afghanistan, Ukraine, Sri Lanka, or Angola, it is our obligation to stand alongside those communities for as long as it takes. I often think of HALO as a bridge between war and peace. We go where others cannot or will not go, into minefields, bombed out cities, and unstable frontiers, not because it is easy, but because it is necessary. The work is difficult and sometimes dangerous, but it has meaning.

Every mine we lift, every weapon we destroy, every community we make safe, those are tangible acts of hope. And so, we stay, because if organisations like HALO do not persist in these places, who will?

As chief executive, you often say HALO’s work is about restoring normality. What does that mean to you in real human terms?

James: When I talk about restoring normality, I mean something very simple. War robs people of the cadence of normal life. It takes away safety, predictability, and dignity. A community cannot rebuild because it lives in fear of what lies beneath the soil. HALO’s work is about restoring normal daily life and the ability to plan for tomorrow. When our teams clear a minefield, they are not just removing explosives. They are reopening a field for crops, a path to school, a road to market. That is the essence of what HALO does. We help restore the ordinary, which in the aftermath of war is in fact extraordinary.

Farzana, as a trustee, what drew you personally to HALO’s mission?

Farzana: What drew me to The HALO Trust was the clarity and directness of its impact. HALO protects lives and restores livelihoods in some of the most fragile environments on earth by clearing landmines and explosive remnants of war. HALO operates in thirty-two countries and territories and is often the first one in after conflict. Other aid organisations cannot begin their work until HALO has made the land safe. Once clearance is complete, contaminated land becomes usable again. Farmers can return to their fields. Children can walk to school safely. Communities can move from conflict to post conflict and begin to rebuild their lives with dignity. The more I learned, the more I understood the multilayered nature of HALO’s impact.

HALO hires and trains local staff, ensuring that investment stays within the community. There is a strong focus on employing women and giving them the skills, training, and confidence to build sustainable careers. What resonated most with me was HALO’s focus on simply getting the job done. I will never forget hearing James say that no child should have to walk through a minefield to get to school. That sentence stayed with me and confirmed that this is where I wanted to serve.

HALO’s operations often intersect with politics, security, and humanitarian aid. How do you maintain neutrality while navigating such complex terrains?

James: Neutrality is a discipline. We work in some of the most politically charged and volatile environments on earth, and yet our effectiveness depends entirely on being trusted by all sides. That trust is hard won, and it comes from consistency. We do what we say we will do, we take no political position, and we focus relentlessly on making land safe for civilians. Our neutrality is also strengthened by the fact that the majority of HALO’s staff are local. They are Afghans in Afghanistan, Ukrainians in Ukraine, Sri Lankans in Sri Lanka. In the end, they are part of the communities they serve, and that reflects HALO’s purpose better than any policy document could.

HALO has been active in Sri Lanka for nearly three decades. What are some of the most powerful transformations you have witnessed there?

James: HALO’s work in Sri Lanka is focused on clearing landmines and other explosives from Jaffna, Kilinochchi, and Mullaitivu districts, the most heavily contaminated areas of the 30-year war. Perhaps the most profound measure of our impact is the simple act of return. More than 285,000 displaced people have been able to go back to their homes and lands. In practical terms, that means children can attend school without fear of hidden explosives, farmers can cultivate their fields to feed their families and sell at market, and communities can begin the slow process of rebuilding lives shattered by nearly three decades of conflict. HALO has safely destroyed over a million explosive items, including over 300,000 anti-personnel mines. Around 37 percent of HALO Sri Lanka’s staff are women, many of them widows or single heads of household, and the work enables them not only to support their families but also to contribute directly to making the land safe for future generations.

Sri Lanka’s mine action story is often cited as a global success. What lessons from Sri Lanka can be applied to other post conflict regions?

James: Sri Lanka’s experience shows that mine action is about far more than clearing explosives. It is about restoring the foundations of normal daily life. One key lesson is that clearance must be paired with community engagement. People must be involved at every step, from identifying hazardous areas to shaping priorities, so that the work meets real needs and builds trust. Another lesson is the importance of local ownership. HALO’s teams in Sri Lanka are drawn from the communities they serve. This not only provides livelihoods but ensures that knowledge and skills stay within the country, leaving a lasting legacy of resilience beyond mine removal. Sri Lanka’s deliberate, data driven Completion Survey process is now considered global best practice, ensuring accuracy, inclusivity, and accountability as the nation moves towards being mine impact free.

How has HALO’s work supported reconciliation and rebuilding in northern and eastern Sri Lanka?

James: The north and east were scarred by decades of civil war. By clearing landmines, we are not just making areas safe. We are creating lasting opportunities. Local people, particularly women, gain jobs as deminers and can later farm cleared land. In 2014, we cleared Jaffna railway station and the line itself, reconnecting the region to the rest of the country. We also cleared the main A9 road, vital for trade and travel. Safety unlocks possibility, and once the land is cleared, investment, tourism, and development follow. Who is going to build a factory or a hotel if there are landmines. Once they are gone, the north has as much potential as the rest of Sri Lanka.

Can you share a personal story from the field in Sri Lanka?

James: A local community member from the northern sector of the Muhamalai minefield expressed it best. “Thanks to the deminers for their courage and dedication, the northern part of Muhamalai is once again a place of life, not fear. You gave us more than cleared land. You gave us back our dignity, our way of life, and our hope.” That is what HALO stands for, restoring not just land, but lives.

With Sri Lanka now declared mine impact free in several districts, what are HALO’s next priorities in the country?

James: With nearly 23 square kilometres of contaminated land remaining, there is still work to be done. HALO teams are clearing around 750 landmines per month. Our immediate focus is on completing clearance in Jaffna and Kilinochchi before tackling the dense jungles of Mullaitivu. Completion, a mine impact free Sri Lanka, is in sight. It will be a historic achievement, made possible only through the generosity of our donors and the dedication of our teams.

Before HALO you had a long military career. How did that shape your understanding of conflict and peacebuilding?

James: My military career gave me a front row seat to conflict in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. You see the human consequences up close, families uprooted, and lives destroyed. It taught me that war’s effects outlast the fighting. True peace is not just the absence of conflict. It is the restoration of safety and normality. HALO does that. My military background helps me see both sides, the mechanics of conflict and the human work needed to repair its damage.

Farzana, as a communications leader and advocate, how do you ensure humanitarian stories are told with both accuracy and empathy?

Farzana: Accuracy begins with understanding that trust sits at the heart of HALO. Any gap between what we communicate and the reality on the ground erodes confidence. That is why I believe in spending time in the field, seeing, listening, and learning firsthand. Empathy means telling stories through the voices of those who live them, the deminers, the parents, the farmers, and the children. When we lead by listening, we honour dignity and truth.

What are the biggest challenges in sustaining funding and awareness for demining, especially in regions that no longer dominate headlines?

James: The biggest challenge is visibility. When a war ends, the cameras leave, but the danger remains. Minefields do not disappear with peace agreements. Securing funding for long term recovery is hard when global attention shifts. That is why partnerships with private donors, foundations, and corporations have become vital. They allow us to continue saving lives even when government aid declines. Sustaining awareness is about reminding the world that peace is not just the absence of war. It is the presence of safety.

How does HALO integrate technology and innovation, from drones to artificial intelligence, into its field operations?

James: The weapons have not changed, but the way we clear them has. Drones, satellites, and artificial intelligence mapping now allow us to identify contamination faster. Ground penetrating radar and magnetic resonance help detect mines more accurately. Mechanisation, including machines and robotics, accelerates clearance while reducing risk. My vision is to keep humans at the heart of HALO while equipping them with technology that multiplies their impact.

HALO employs thousands of local staff worldwide. How do you empower communities to lead their own recovery?

James: HALO is fundamentally local. Of 12,000 staff, only about 300 are international. We build capacity within communities, ensuring skills stay even after we leave. Our motto is simple. Get the last landmine out of the ground for good. That mission ends when the land is safe, and the community is self-sufficient. The people we hire today often become tomorrow’s leaders in development and reconstruction.

Beyond the technical aspect of demining, what emotional toll does this work take on your teams, and how do you support them?

James: The emotional toll is real. Our teams witness trauma and risk their lives daily. We provide psychological support, peer networks, and training. What sustains them is purpose, knowing they are saving lives and giving communities a future. The pride of seeing a family return home safely or children playing in a once mined field outweighs the hardship. Purpose is the greatest antidote to fear.

In a world shaped by new kinds of conflict, cyber, environmental, and ideological, how does HALO evolve to stay relevant?

James: Conflict is evolving, but HALO’s purpose endures, protecting people from immediate harm. We adapt by embracing technology and expanding into urban clearance and weapon control, while staying grounded in our core humanitarian mission. No matter how war changes, it still leaves a human cost. HALO’s role is to meet that cost head on.

What has been your most humbling moment working with HALO?

James: The courage of our deminers humbles me every day. Many come from affected communities themselves. They have lost loved ones, yet they return to the same fields to make them safe for others. Their discipline, dedication, and quiet heroism inspire me deeply.

Farzana: My most humbling moments are always in the field, meeting the men and women who risk their lives daily to protect their own communities. Standing beside them and hearing their stories, you understand that heroism is not loud. It is steadfast, patient, and deeply human.

How can governments, corporations, and individuals contribute to the goal of a mine free world?

James: When I joined HALO, most funding came from governments. As priorities shifted, we turned to private and corporate partnerships, and the response has been extraordinary. Private support now makes up nearly a third of our income, about 50 million pounds a year. It shows that people and businesses are willing to take responsibility for global stability. Every contribution, large or small, brings us closer to a mine free world.

Looking ahead ten years, what does success look like for The HALO Trust and for each of you personally?

James: Success means HALO playing a central role in addressing the aftermath of conflict. We are not diplomats, but in rural demining, urban bomb disposal, and weapons management, we provide real and practical solutions. HALO remains one of the world’s best kept secrets. Many know our connection to Princess Diana, but few realise our scale. My goal is to make HALO as recognised for rebuilding peace as it is for removing mines.

Farzana: Success for HALO means seeing every country we serve declared mine free. It also means using new technology, including artificial intelligence, data mapping, and advanced detection, to make demining faster and safer. For me personally, success means continuing to serve HALO’s mission, to amplify the voices of those whose lives are transformed by safe land, and to help ensure that hope and possibility can take root again where fear once lay buried.