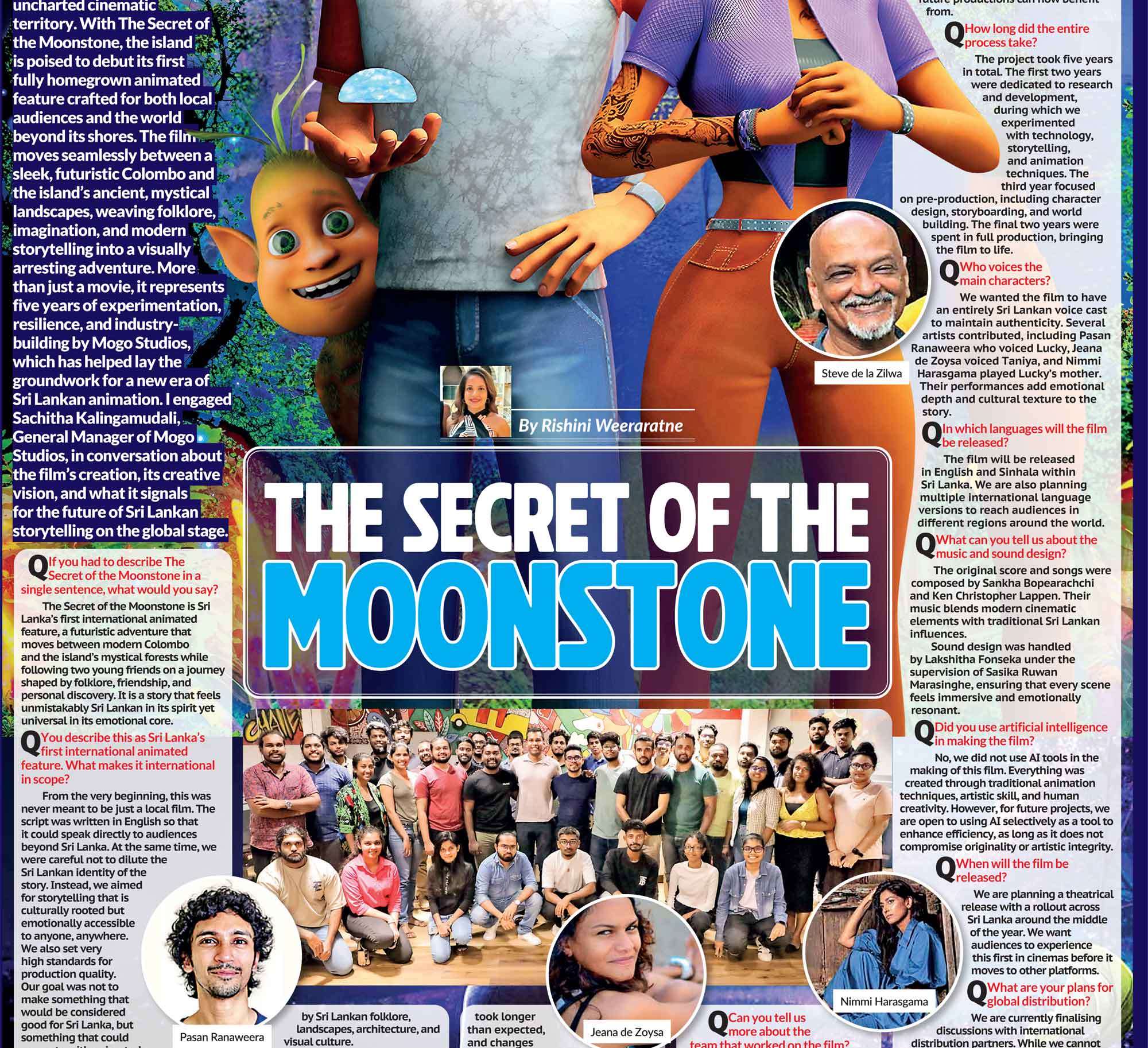

At the most fundamental level of human biology, sex differences begin with chromosomes. Females typically carry two X chromosomes, while males carry one X and one Y. On the surface, this distinction appears straightforward. Yet beneath it lies one of the most intricate regulatory systems in genetics, a process that makes female biology uniquely complex, adaptable, and resilient. This process is known as X chromosome inactivation, and it reshapes how female bodies develop, function, and respond to disease throughout life. The challenge begins with genetic dosage.

The X chromosome is large and gene rich, carrying hundreds of genes essential for normal development, brain function, metabolism, and immunity. If females were to express genes from both X chromosomes at full capacity, they would produce double the amount of certain proteins compared to males. Such an imbalance would be biologically harmful. Nature’s solution is elegant and radical. Early in embryonic development, female cells silence one of their two X chromosomes, ensuring that gene expression remains balanced between the sexes.

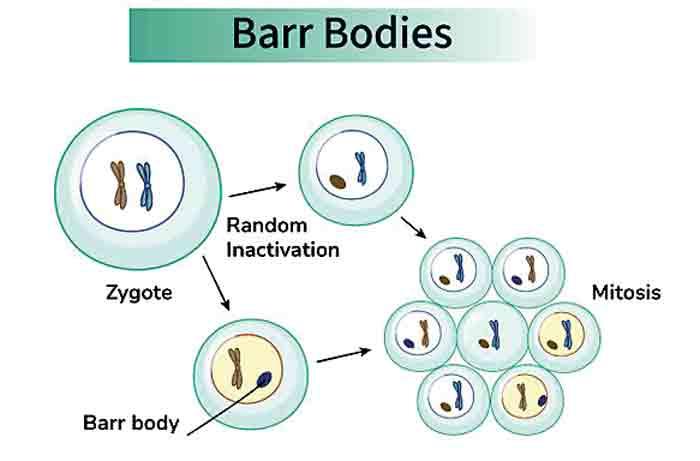

This silencing occurs remarkably early, just days after fertilization, when the embryo consists of only a small number of cells. At this stage, each cell independently and randomly chooses which X chromosome to inactivate. In some cells, the X inherited from the mother is switched off. In others, it is the paternal X that becomes silent. Once a cell makes this decision, it commits to it permanently. Every daughter cell produced through division retains the same inactive X chromosome as the original cell. As a result, the adult female body becomes a mosaic composed of millions of cell populations, each expressing genes from only one of the two X chromosomes. This mosaicism is one of the defining features of female biology. Unlike males, whose cells uniformly express the same single X chromosome, females contain a patchwork of genetic expression patterns. Different tissues, and even neighboring cells within the same tissue, may rely on different versions of X linked genes. This creates diversity at a cellular level that is invisible to the naked eye but profoundly influential in health and disease.

One of the clearest visual demonstrations of X chromosome inactivation appears in calico cats. Their distinctive patches of black, orange, and white fur are not random decorations, but living illustrations of genetic mosaicism. The genes responsible for coat color in cats are located on the X chromosome. Because female cats have two X chromosomes, different skin cells activate different color genes depending on which X chromosome remains active. As those cells divide and spread, they form visible patches of color. Male cats, with only one X chromosome, almost never display this pattern. What is striking in animals is quietly replicated inside the human body, not in fur, but in organs, tissues, and systems essential to survival.

Inside each female cell, the inactive X chromosome does not vanish. Instead, it condenses into a compact structure called a Barr body, visible under a microscope as a dense spot within the cell nucleus. This condensed chromosome is largely silent, but not completely. Some genes escape inactivation and remain active on both X chromosomes. These escape genes add another layer of complexity to female genetics, as they can be expressed at higher levels than in males. Scientists believe these genes play roles in immune regulation, brain development, and metabolic control, contributing to subtle but significant biological differences between the sexes. The presence of two X chromosomes and the process of inactivation also provide females with a powerful form of genetic protection. Many genetic disorders are linked to mutations on the X chromosome. In males, a single faulty gene on their only X chromosome is enough to cause disease. Females, however, often carry a healthy version of the gene on their second X chromosome. Because of mosaicism, many of their cells will still express the functional gene, reducing or completely masking symptoms. This buffering effect explains why conditions such as hemophilia and certain forms of color blindness are far more common and severe in males.

Yet this protection is not absolute. X chromosome inactivation is random, but randomness does not always produce perfect balance. In some individuals, one X chromosome is preferentially inactivated in a majority of cells. This phenomenon, known as skewed X inactivation, can have significant consequences. If the X chromosome carrying the healthy gene is inactivated more often, a female carrier of an X linked condition may experience symptoms that range from mild to severe. This variability helps explain why female carriers of disorders like Duchenne muscular dystrophy or fragile X syndrome can show dramatically different clinical outcomes, from near total absence of symptoms to noticeable physical or cognitive effects. The implications of skewed inactivation extend beyond rare genetic disorders. Researchers have increasingly linked X chromosome behavior to autoimmune diseases, many of which disproportionately affect women. Conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis occur far more frequently in females than in males. One leading hypothesis suggests that incomplete silencing of immune related genes on the X chromosome, or skewed inactivation patterns, may lead to heightened immune activity. In this context, the same genetic complexity that provides protection against some diseases may increase vulnerability to others.

One of the clearest visual demonstrations of X chromosome inactivation appears in calico cats. Their distinctive patches of black, orange, and white fur are not random decorations, but living illustrations of genetic mosaicism.

X chromosome inactivation also challenges long held assumptions in medicine. For decades, male biology was treated as the default model for human health, with female differences attributed largely to hormones. Modern genetics reveals that this view is incomplete. Female biology is not simply male biology with estrogen added. It is structured differently from the earliest stages of development, governed by genetic mechanisms that influence everything from organ formation to cellular repair.

This understanding has profound implications for personalized medicine. Drug metabolism, treatment effectiveness, and side effect profiles can differ between individuals based on how genes are expressed. In females, X linked gene expression adds another variable. Two women with the same diagnosis and the same genetic mutation may respond differently to treatment because their X chromosome inactivation patterns differ. As medicine moves toward more individualized approaches, accounting for these patterns may improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes.

The influence of X chromosome inactivation may also extend into aging and longevity. Women, on average, live longer than men across most populations worldwide. While social and environmental factors certainly play a role, genetics may contribute as well. Having two X chromosomes provides a form of redundancy. As cells accumulate damage with age, the presence of an alternative functional gene copy may help maintain cellular function for longer. Some studies suggest that shifts in X linked gene expression occur over time, potentially influencing how tissues age and how resilient the brain remains against neurodegenerative processes.

In the brain, X chromosome inactivation adds yet another layer of intrigue. Many genes involved in neural development and cognitive function are located on the X chromosome. Mosaic expression of these genes may contribute to variability in learning, memory, and cognitive resilience. While science is still unraveling these connections, it is becoming increasingly clear that female neurological development cannot be fully understood without considering X chromosome dynamics.

Importantly, X chromosome inactivation is not a static or simplistic process. It is regulated by a complex network of molecular signals, including noncoding RNA molecules that coat the chromosome destined for silencing and trigger structural changes. This regulatory choreography ensures that inactivation is stable across billions of cell divisions while still allowing flexibility where necessary. Such precision underscores how evolution has prioritized balance over uniformity in female biology.

The broader lesson of X chromosome inactivation is that biological sex is deeply embedded in genetics, not merely layered on through hormones or reproductive organs. From the first days of embryonic life, female development follows a distinct genetic pathway shaped by randomness, regulation, and adaptability. This pathway produces bodies that are internally diverse, capable of compensating for genetic faults, but also susceptible to unique vulnerabilities. What calico cats display openly through their fur, human females carry invisibly within every tissue. Each woman is, at a cellular level, a living mosaic. Some cells express one genetic legacy, others express another, all coexisting in a finely tuned balance. This complexity is not an accident or an imperfection. It is a survival strategy, one that has allowed female bodies to adapt, endure, and thrive across generations.

As scientific research continues to explore the nuances of X chromosome inactivation, it challenges outdated notions of a single standard biology. It calls for greater attention to sex specific research, more inclusive clinical trials, and medical models that reflect real biological diversity. Understanding female genetics is not about emphasizing difference for its own sake, but about recognizing the mechanisms that shape health, disease, and resilience. In the end, X chromosome inactivation is a quiet reminder of how sophisticated life truly is. Beneath the apparent simplicity of two chromosomes lies a system that embraces randomness to achieve balance, complexity to ensure protection, and diversity to enhance survival. Female biology, far from being a variation on a male template, is a carefully regulated genetic architecture in its own right, one that science is only beginning to fully appreciate.