Nihilist Penguin

“I make a promise to the clouds, and walk to the summit, to reclaim the sky that should have been mine.”

There are moments in documentary filmmaking that quietly outlive their original purpose. Removed from their initial context and encountered again years later, they begin to speak in ways their creators may never have intended. A brief scene from Werner Herzog’s 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World has become one such moment. What was once a troubling observation of animal behavior has, nearly two decades later, transformed into one of the most widely shared and philosophically interpreted viral images of 2026.

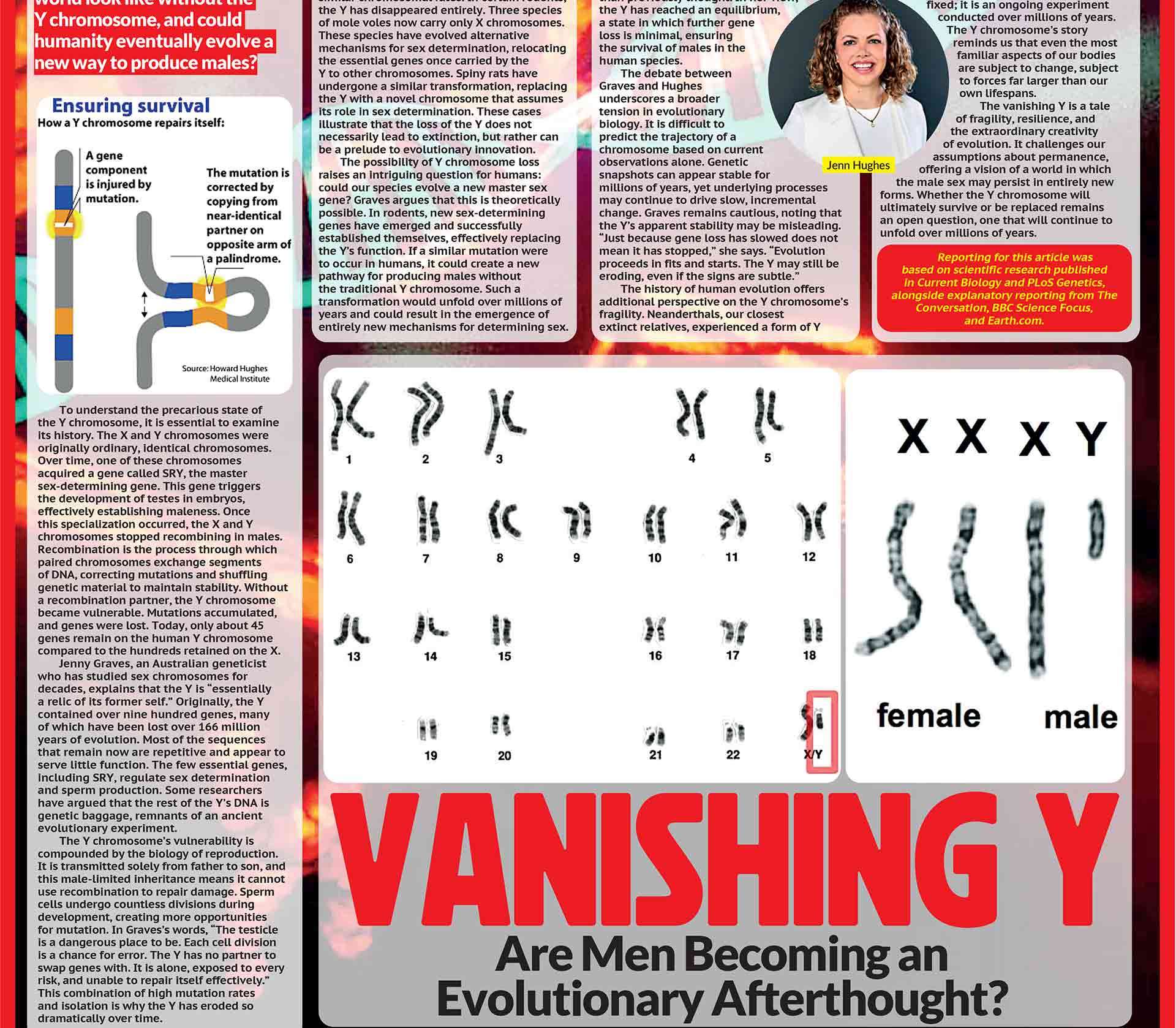

The footage is simple. An Adélie penguin separates itself from its colony in Antarctica and begins walking inland. The rest of the group moves toward the sea, following routes shaped by instinct and survival. This penguin pauses, turns, and heads in the opposite direction. It moves toward distant mountains that offer no food, no shelter, and no known purpose. Herzog’s narration is measured and restrained. At the end, he asks a question that has since become inseparable from the image. But why?

The footage is simple. An Adélie penguin separates itself from its colony in Antarctica and begins walking inland. The rest of the group moves toward the sea, following routes shaped by instinct and survival. This penguin pauses, turns, and heads in the opposite direction. It moves toward distant mountains that offer no food, no shelter, and no known purpose. Herzog’s narration is measured and restrained. At the end, he asks a question that has since become inseparable from the image. But why?

Scientifically, the answer is not elusive. Penguin researchers featured in the documentary, including Dr. David Ainley, explain that such behavior, while rare, does occur. Disorientation, illness, neurological malfunction, or environmental stress can cause an animal to abandon established patterns. The mountains the penguin walks toward are approximately seventy kilometers away. There is nothing there that could sustain it. From a biological standpoint, its fate was almost certainly sealed.

And yet, despite this clarity, the image refuses to remain confined to science.

In January 2026, the clip resurfaced across social media platforms, re-edited with slower pacing and paired with a pipe organ version of “L’Amour Toujours.” The contrast between the solemn music and the penguin’s steady movement proved strangely arresting. Within days, the video spread across TikTok, Instagram, Reddit, and beyond. Users layered it with captions about burnout, quiet quitting, emotional exhaustion, and the urge to step away from prescribed paths. The bird was given a name that would define its afterlife online. The Nihilist Penguin.

The term is inaccurate, yet revealing. Nihilism suggests despair or the belief that life is fundamentally meaningless. What many viewers appear to project onto the penguin is not hopelessness, but refusal. A refusal to follow instinct without question. A refusal to remain within a system that feels repetitive, constricting, or hollow, even if it is safe. In the penguin’s solitary walk, people recognize something uncomfortably familiar.

Herzog himself does not frame the moment as heroic. His tone is unsettled rather than admiring. The penguin is not portrayed as enlightened or awakened. It is not making a conscious choice in any philosophical sense. Scientists have been careful to remind audiences that animals do not engage in symbolic rebellion. The behavior represents an anomaly, not intention.

Still, cultural meaning does not require biological accuracy. Symbols endure not because they are factual, but because they give shape to emotions that resist easy explanation.

The image of the penguin walking alone across the ice has become a vessel for a generation grappling with fatigue and disillusionment. Many see in it the quiet desire to leave systems that no longer feel livable. To step away without a clear alternative. To keep moving, not toward success or fulfillment, but simply away from what feels unbearable. The penguin does not announce its departure. It does not struggle or collapse. It continues.

That calm persistence is what gives the image its power.

We live in a time that values direction above all else. Progress must be measurable. Choices must be justified. Deviation is often treated as failure. Against this backdrop, the act of walking in the wrong direction carries unexpected emotional weight. The penguin’s movement appears irrational, even self-destructive. And yet, it is steady, deliberate, and uninterrupted.

There is a line often attributed to the penguin in viral edits. “I have no wings, so I can’t fly. I’ll climb the highest mountains, so I may touch the sky.” The line is fictional, but the sentiment resonates. It speaks to limitation and aspiration existing side by side. To wanting something deeply while knowing it may never be reached. To attempting anyway.

What makes the penguin’s journey unsettling is not simply that it leads toward death, but that it resists interpretation. Some view it as nihilistic. Others frame it as an act of rebellion against routine and conformity. Still others see it as strangely motivational, a symbol of choosing one’s own direction regardless of consequence. Each interpretation says less about the bird and more about the viewer.

It is possible that the penguin was simply lost. It is possible that illness or internal disruption guided its steps. It is also possible that loneliness, pressure, or internal turbulence played a role in ways science cannot fully map. We cannot know what the penguin experienced internally, and any attempt to assign intention risks projection. What matters is not the certainty of explanation, but the recognition that deviation does not always come from clarity. Sometimes it comes from overwhelm.

The penguin did not stand still. It did not wait for rescue. It did not remain frozen between choices. It moved. That movement, regardless of outcome, is what continues to trouble and comfort viewers alike.

In this sense, the penguin becomes less a symbol of nihilism and more a reflection of human restlessness. A reminder that survival alone does not always feel sufficient. That meaning, however undefined, remains something people continue to seek, even when the path toward it appears irrational or unwise. The penguin’s fate was never documented.

No one followed it to the end of its journey. Scientists consider the outcome a certainty, but certainty does not erase resonance. The absence of closure allows the image to linger, suspended between explanation and imagination.

Perhaps that is why it continues to circulate. It does not offer answers. It does not instruct or console. It simply presents a moment of divergence and leaves it unresolved. Herzog’s question remains unanswered not because it cannot be answered, but because answering it would diminish its power.

There is also something important in resisting the urge to romanticize the penguin’s path. Walking toward destruction does not automatically make an act noble. Choosing differently does not guarantee wisdom. The penguin may have walked with regret, confusion, or nothing at all. Satisfaction and sorrow are human concepts, and we cannot assign them with confidence.

What we can acknowledge is this. The penguin did not remain where it was simply because it was expected to. It chose motion over stasis. Whether driven by confusion, pressure, or some internal disturbance, it continued. That persistence, stripped of metaphor, remains quietly profound.

In a world that often demands certainty before movement, the penguin walks without it. In a culture that insists on purpose before permission, it moves anyway. Not toward freedom or enlightenment, but toward something different.

The image endures because it captures a moment many recognize but rarely articulate. The moment when staying feels impossible, and leaving feels no clearer. The moment when movement itself becomes the only available response.

“I make a promise to the clouds, and walk to the summit, to reclaim the sky that should have been mine.”

Not because the sky is guaranteed. Not because the summit is reachable. But because standing still, under the weight of expectation and repetition, feels like a quieter kind of ending.

[For readers inspired to see the full documentary, Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World is available to stream on Netflix (select regions) and on Prime Video.]