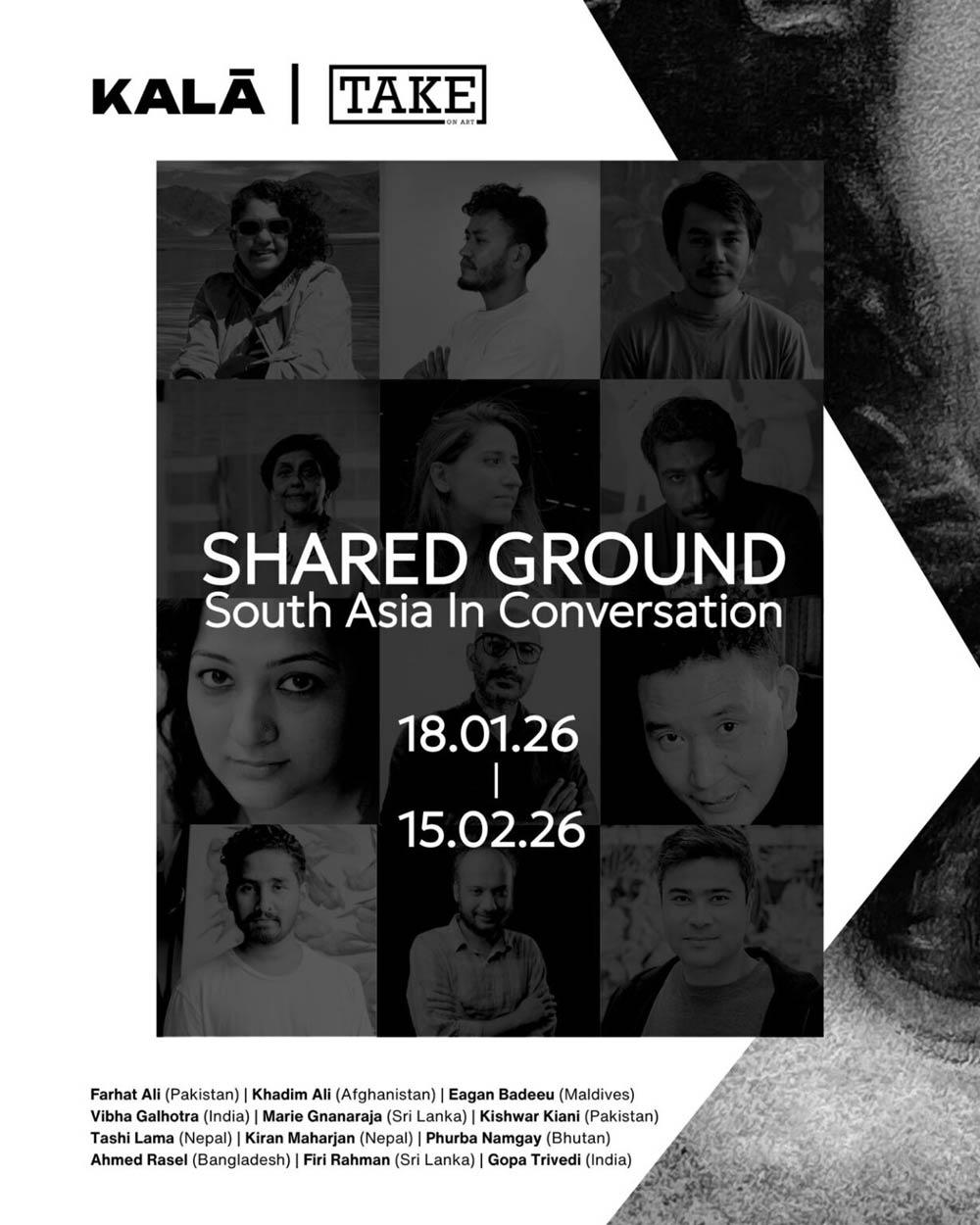

At a moment when Colombo is quietly reasserting itself as a site of critical cultural thought, KALĀ 2026 arrives not merely as an exhibition platform, but as a carefully constructed space for sustained regional dialogue. Rooted in South Asia yet shaped by its diasporas, KALĀ brings together artistic practice, research, writing, and embodied knowledge in ways that resist easy categorization.

At the heart of this initiative are two figures whose work has long shaped how contemporary South Asian art is seen, written about, and sustained. Saskia Fernando, Founder of KALĀ and Director of Saskia Fernando Gallery, has spent over a decade building infrastructures for Sri Lankan contemporary art; creating spaces that privilege long-term engagement over spectacle, and regional conversation over isolation. With KALĀ, her practice extends beyond representation into facilitation, positioning Colombo as an active participant in cross-border cultural exchange.

Alongside her is Bhavna Kakar, Editor-Publisher of TAKE on Art and Founder-Director of Latitude 28, whose editorial and curatorial work has played a pivotal role in shaping critical discourse across South Asia. Known for her commitment to research-driven, archival, and slow art practices, Kakar brings to KALĀ a deep intellectual framework; one that challenges dominant narratives of validation while foregrounding voices and histories often overlooked.

Together, Fernando and Kakar envision KALĀ as a living platform, one that holds space for difference, complexity, and sustained dialogue across borders. In conversation with them, we explore what it means to build cultural infrastructures in post-crisis contexts, how regional solidarities can be formed without flattening histories, and why Colombo, at this moment, matters.

SASKIA FERNANDO

Founder, KALĀ | Director, Saskia Fernando Gallery

KALĀ 2026 positions Colombo as a site for cross-border artistic exchange across South Asia. What felt urgent or missing in Sri Lanka’s cultural landscape that led you to initiate this platform at this moment?

Collaboration. Across every space and institution, there was a growing sense that we needed to work toward creating new dialogues and partnerships. We connected easily with partners across the region who had made similar observations.

The name KALĀ carries ideas of time, craft, and embodied practice. How does this philosophy shape the way the platform operates beyond a conventional exhibition format?

We work as a platform, engaging with sustainable projects based on our access to funding and support. These include exhibitions, residency exchanges, talks, a production grant, and workshops.

KALĀ brings together artists and practitioners from across South Asia and its diasporas—regions often spoken of collectively yet shaped by very different histories. How do you create space for regional solidarity without erasing difference or complexity?

By encouraging dialogue and keeping the platform open to transformation and evolution. We are not restricted by a single format and retain the flexibility to respond to what we observe as the region’s evolving needs.

Much of your work has involved shifting how Sri Lankan contemporary art is perceived, both locally and internationally. What kinds of conversations do you hope KALĀ opens within Colombo itself?

We hope to act as a catalyst for new connections and networks between individuals and organizations. This is fundamentally our aim.

KALĀ balances intimate formats such as workshops and walkthroughs with public-facing panels and performances. How important was it that the platform feels open and accessible rather than elite or insular?

Incredibly important. It is not an easy barrier to break, but we make a conscious effort to remain publicly accessible. We are proud that our student visits and open calls have succeeded in drawing applicants from diverse communities.

You have worked across galleries, fairs, institutions, and now a cross-border platform. How has your role evolved from representing artists to facilitating regional dialogue?

For me, it is one and the same. Facilitating regional dialogue is part of my role, and KALĀ offers another platform to do so. The fairs we participate in and the galleries we collaborate with are also integral to this process. I don’t see it as an individual effort.

On a personal note, after years of building spaces for others, what does this moment represent for you as a cultural practitioner?

It feels like a comfortable space. We have established ourselves and are now focused on long-term impact rather than short-term events or festivals.

BHAVNA KAKAR

Editor-Publisher, TAKE on Art | Founder-Director, Latitude 28

TAKE on Art has long foregrounded critical writing, research, and archival thinking. What drew you to collaborating with KALĀ, and why did this dialogue feel necessary now?

What drew me to KALĀ was a shared commitment to thinking from within the region rather than about it from elsewhere. KALĀ is not simply a venue or an event platform; it is an intellectual proposition that values process, conversation, and care. At a time when South Asia is experiencing profound political, ecological, and cultural shifts, it felt urgent to create a space where dialogue could unfold laterally across borders, without mediation by Western frameworks of validation. Listening, at this moment, has itself become a radical act.

South Asian contemporary art is often framed and validated through Western institutions and biennales. How does a platform like KALĀ challenge those existing circuits of recognition?

KALĀ challenges these circuits by refusing the extractive logic that often governs global art visibility. Instead of positioning South Asia as a site to be discovered, it centers regional voices, concerns, and temporalities. Recognition emerges through proximity, dialogue, and sustained engagement rather than scale or spectacle. By grounding itself in Colombo, KALĀ reclaims agency over how narratives are produced, shared, and remembered—on our own terms and for our own publics first.

Your work has consistently questioned how art history is written and whose voices are preserved. In what ways does KALĀ extend that editorial and intellectual mission into a live public platform?

TAKE on Art has always invested in building archives that are porous, contested, and alive. KALĀ extends this editorial impulse into real time, allowing ideas to be tested through encounter through performance, conversation, disagreement, and embodied presence. What might remain fixed on the page becomes process and relational exchange. In this sense, KALĀ is an editorial space without margins, where history is actively negotiated.

As an editor, you have advocated for slow engagement over spectacle. How do live performances and embodied practices complicate traditions of art writing and critique?

Live, embodied practices resist closure. They demand attentiveness, vulnerability, and presence, qualities that writing must learn to emulate rather than dominate. Performance foregrounds affect, temporality, and risk, asking writers to move beyond theory and write from lived encounter. This has shaped initiatives such as the Art Writers’ Award, developed with Pro Helvetia, which prioritizes sustained research and long-form inquiry over immediate commentary.

Collaboration across South Asia involves political, logistical, and ethical considerations. What were some of the quieter challenges and unexpected rewards of shaping this platform across borders?

One challenge was negotiating uneven infrastructures of mobility, funding, and visibility without allowing those disparities to create hierarchy. There were also sensitivities around language, representation, and historical memory that required patience and trust. The unexpected reward was generosity; artists and collaborators repeatedly showed a willingness to listen, adapt, and hold space for one another. These moments of care became part of the outcome.

What responsibilities do senior cultural practitioners carry at moments when regions are redefining themselves?

The responsibility is to make room to share resources, visibility, and authorship. This is not about paternal mentorship, but accountability. We must question our own authority, remain open to being challenged, and sustain platforms that outlive us, ensuring younger voices are not only included, but heard on their own terms.

What histories might future scholars trace back to moments like KALĀ 2026?

I hope they trace histories of regional solidarity; moments when artists, writers, and institutions chose collaboration over fragmentation. KALĀ 2026 may be remembered as a moment when collaboration was articulated not as strategy, but as ethic, rooted in care, accountability, and shared authorship.

Finally, after years of institution-building, what continues to excite you about beginning a new conversation in Colombo?

The act of beginning again. Colombo carries layered histories of trade, conflict, resilience, and cultural exchange, making it a powerful site for dialogue. Each new context asks us to listen differently and remain open to what we do not yet know. That sense of possibility continues to fuel my work.