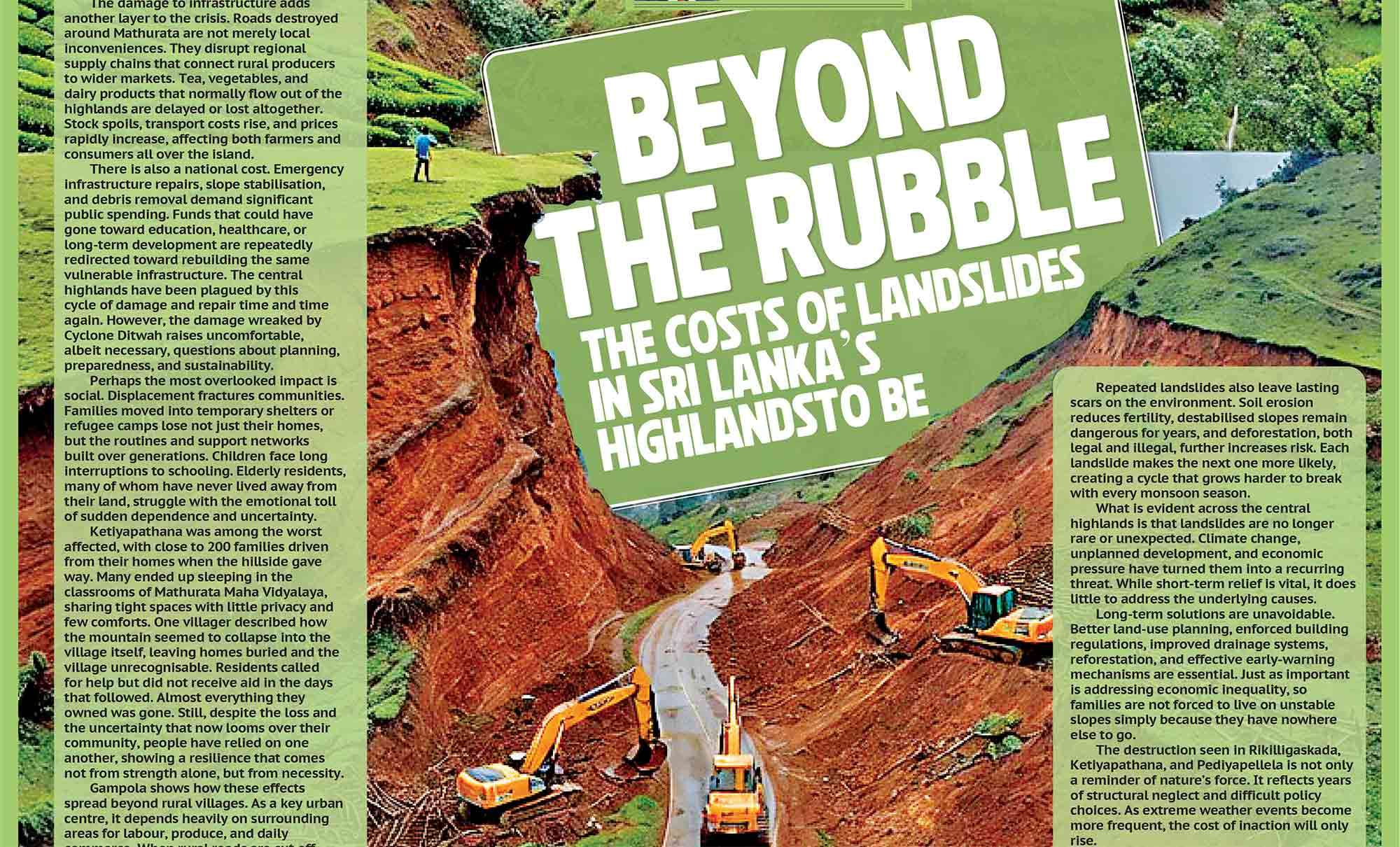

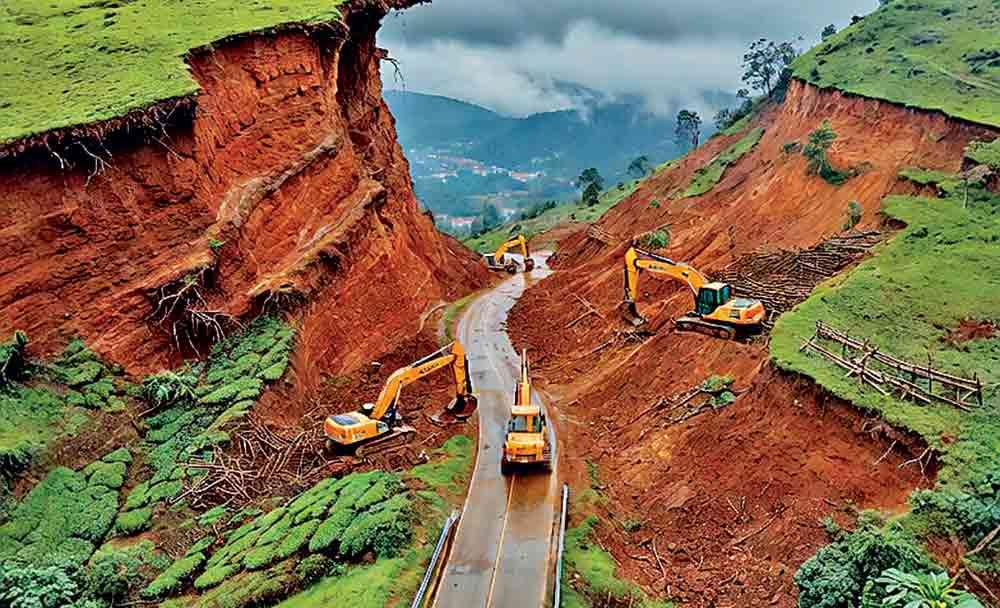

In Sri Lanka’s central highlands, landslides are often reduced to images of collapsed hillsides, crushed homes, and roads swallowed by mud. Those scenes are striking, but they tell only part of the story. The real damage runs deeper, quietly reshaping lives, economies, and entire communities in places such as Rikilligaskada, Mathurata, Ketiyapathana, and Gampola.

In Sri Lanka’s central highlands, landslides are often reduced to images of collapsed hillsides, crushed homes, and roads swallowed by mud. Those scenes are striking, but they tell only part of the story. The real damage runs deeper, quietly reshaping lives, economies, and entire communities in places such as Rikilligaskada, Mathurata, Ketiyapathana, and Gampola.

For many families in these areas, livelihoods are tied directly to the land. Tea estates, small farms, and daily-wage work are not just sources of income; they are the foundation of survival. When a landslide occurs, it does more than destroy a harvest. It wipes out productive land altogether. Tea fields buried under tonnes of earth represent years of lost effort and investment. Even if the land can be restored, tea bushes take years to mature, leaving families without a stable income for long periods.

The immediate result is unemployment. Estate workers and small farmers suddenly find themselves with no work and few alternatives. With limited opportunities nearby, many are pushed into debt, forced to rely on relief aid, or compelled to migrate to already strained urban centres. Over time, this deepens poverty and increases vulnerability, making the same communities more exposed when the next disaster strikes.

The damage to infrastructure adds another layer to the crisis. Roads destroyed around Mathurata are not merely local inconveniences. They disrupt regional supply chains that connect rural producers to wider markets. Tea, vegetables, and dairy products that normally flow out of the highlands are delayed or lost altogether. Stock spoils, transport costs rise, and prices rapidly increase, affecting both farmers and consumers all over the island.

There is also a national cost. Emergency infrastructure repairs, slope stabilisation, and debris removal demand significant public spending. Funds that could have gone toward education, healthcare, or long-term development are repeatedly redirected toward rebuilding the same vulnerable infrastructure. The central highlands have been plagued by this cycle of damage and repair time and time again. However, the damage wreaked by Cyclone Ditwah raises uncomfortable, albeit necessary, questions about planning, preparedness, and sustainability.

Perhaps the most overlooked impact is social. Displacement fractures communities. Families moved into temporary shelters or refugee camps lose not just their homes, but the routines and support networks built over generations. Children face long interruptions to schooling. Elderly residents, many of whom have never lived away from their land, struggle with the emotional toll of sudden dependence and uncertainty.

Ketiyapathana was among the worst affected, with close to 200 families driven from their homes when the hillside gave way. Many ended up sleeping in the classrooms of Mathurata Maha Vidyalaya, sharing tight spaces with little privacy and few comforts. One villager described how the mountain seemed to collapse into the village itself, leaving homes buried and the village unrecognisable. Residents called for help but did not receive aid in the days that followed. Almost everything they owned was gone. Still, despite the loss and the uncertainty that now looms over their community, people have relied on one another, showing a resilience that comes not from strength alone, but from necessity.

Gampola shows how these effects spread beyond rural villages. As a key urban centre, it depends heavily on surrounding areas for labour, produce, and daily commerce. When rural roads are cut off, traffic congestion worsens, markets feel the strain, and emergency services are slowed. Landslides, it becomes clear, are not a rural issue alone, but a regional problem with national consequences.

Repeated landslides also leave lasting scars on the environment. Soil erosion reduces fertility, destabilised slopes remain dangerous for years, and deforestation, both legal and illegal, further increases risk. Each landslide makes the next one more likely, creating a cycle that grows harder to break with every monsoon season.

What is evident across the central highlands is that landslides are no longer rare or unexpected. Climate change, unplanned development, and economic pressure have turned them into a recurring threat. While short-term relief is vital, it does little to address the underlying causes.

Long-term solutions are unavoidable. Better land-use planning, enforced building regulations, improved drainage systems, reforestation, and effective early-warning mechanisms are essential. Just as important is addressing economic inequality, so families are not forced to live on unstable slopes simply because they have nowhere else to go.

The destruction seen in Rikilligaskada, Ketiyapathana, and Pediyapellela is not only a reminder of nature’s force. It reflects years of structural neglect and difficult policy choices. As extreme weather events become more frequent, the cost of inaction will only rise.

Preventing future disasters is no longer just an environmental concern. It is an economic and social necessity. Sri Lanka’s central highlands cannot afford to keep rebuilding the same roads, re-housing the same families, and mourning the same losses year after year.