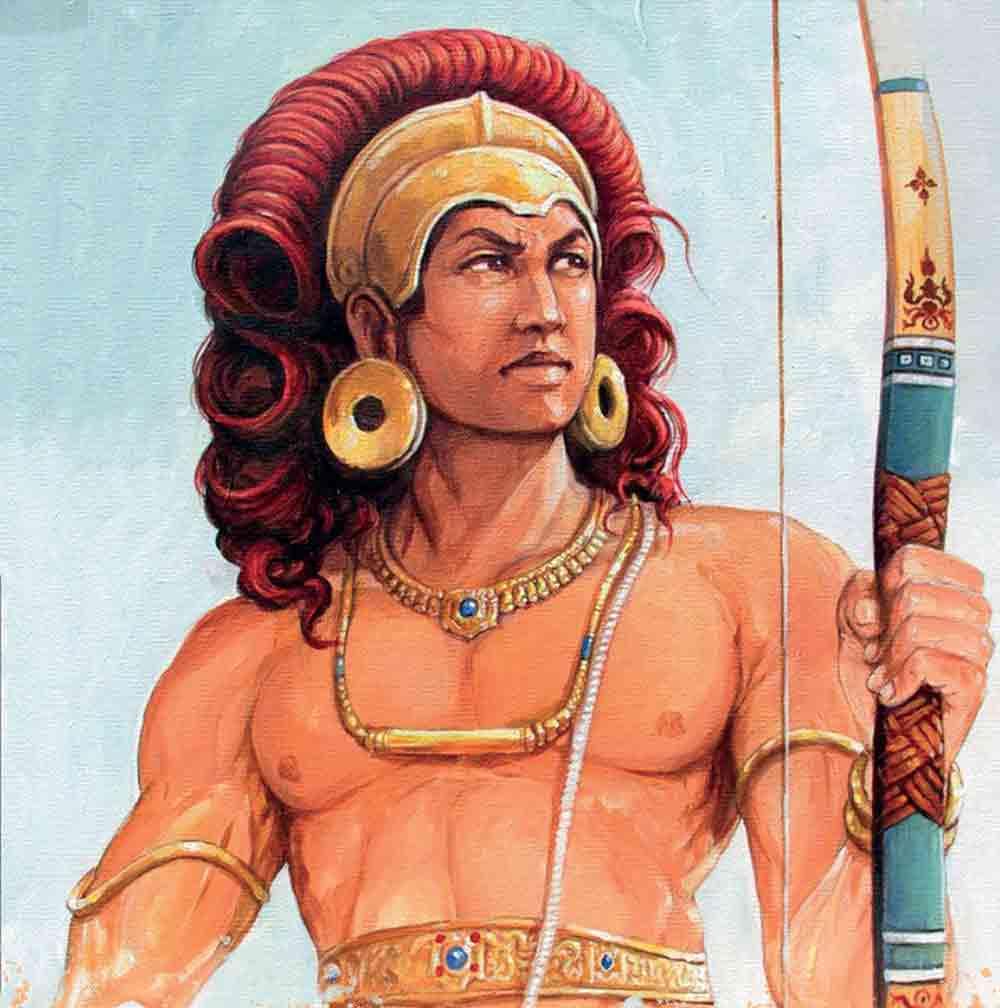

The Most Dangerous Throne in the Indian Ocean. Medieval Sri Lanka did not lack kings. It lacked safe ones. From Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa and into the fragmented courts of the thirteenth century, Sinhala monarchs were poisoned, stabbed, strangled, exiled, ritually abandoned, or quietly erased from power. Yet this was not chaos. It was a system. Kings were removed not by popular revolt, not by constitutional process, but through a carefully calibrated interaction between court violence, monastic judgment, and elite consensus. Sri Lanka developed one of the most lethal but controlled regimes of political removal in the medieval world. Kings who failed did not merely lose battles. They lost legitimacy, protection, and ultimately their lives. This article examines how kings were actually removed, and why the kingdom survived them.

The Most Dangerous Throne in the Indian Ocean. Medieval Sri Lanka did not lack kings. It lacked safe ones. From Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa and into the fragmented courts of the thirteenth century, Sinhala monarchs were poisoned, stabbed, strangled, exiled, ritually abandoned, or quietly erased from power. Yet this was not chaos. It was a system. Kings were removed not by popular revolt, not by constitutional process, but through a carefully calibrated interaction between court violence, monastic judgment, and elite consensus. Sri Lanka developed one of the most lethal but controlled regimes of political removal in the medieval world. Kings who failed did not merely lose battles. They lost legitimacy, protection, and ultimately their lives. This article examines how kings were actually removed, and why the kingdom survived them.

Regicide Was Not a Crime, It Was a Solution

Modern states treat the killing of a ruler as treason. Medieval Sri Lanka treated it as a corrective. The chronicles record assassinations with striking restraint. Kings are “removed,” “cut down,” or “destroyed,” often without moral outrage. What mattered was not the act but the justification. If a ruler was deemed adhammika (unrighteous), his death restored order. The clearest example is King Vijayabāhu II of Polonnaruwa. He reigned for barely a year before being assassinated in 1187. The Cūlavamsa offers no lament. His death is reported as a fact, followed immediately by political reorganisation. No civil war followed. No sacral horror accompanied the act. Why? Because the king had already lost elite confidence. In Sri Lanka, kingship ended before the blade fell.

The Palace Was the Battlefield

Assassination was rarely public. It occurred inside palaces, not on fields. Court officials, guards, and relatives were the primary agents of regicide. This is visible across centuries. Kings were killed while bathing, eating, sleeping, or performing ritual. Violence was intimate, targeted, and swift. This was not random betrayal. It was institutionalised vulnerability. A king surrounded by attendants was surrounded by potential executioners. Loyalty was conditional. Once withdrawn, proximity became fatal. The palace was designed not only to elevate the king but to contain him.

The Sangha Did Not Kill Kings, It Licensed Their Removal

The Buddhist Sangha did not wield weapons. It wielded something more powerful: moral authorization. Chronicles repeatedly describe kings losing monastic support before their downfall. Donations were rejected. Ritual participation was withdrawn. Monks relocated relics or absented themselves from court ceremonies. Once this occurred, a king was politically dead. Leslie Gunawardana demonstrated that monastic silence functioned as a signal to elites. Generals, governors, and courtiers understood that violence would carry no karmic stigma if directed at an unrighteous ruler. The Sangha did not order assassinations. It made them permissible.

Why No Dynastic Bloodbath Followed

In Europe, killing a king often triggered dynastic war. In Sri Lanka, it rarely did. This is because kingship was not dynastic in an absolute sense. Bloodline mattered, but legitimacy was situational. A ruler did not inherit the throne automatically. He occupied it provisionally. The Tooth Relic, monastic endorsement, and elite consent mattered more than genealogy. This prevented vendetta cycles. When a king fell, his removal was framed as correction, not usurpation. The throne was not sacred because of the man. The man was sacred because of the throne. Once that bond broke, killing him did not desecrate kingship.

Case Study: Polonnaruwa’s Killing Ground

Polonnaruwa provides the clearest sequence of controlled royal elimination. After Parākramabāhu I, the throne became unstable. Kings rose rapidly and fell violently:

- Vijayabāhu II assassinated

- Mahinda VI deposed within weeks

- Sahassa Malla removed after misrule

- Dharmāśoka murdered

- Queen Lilavati installed, removed, restored, then removed again

This was not anarchy. It was elite triage. Each ruler was tested against three criteria: control of military factions, acceptance by the Sangha, and capacity to maintain order. Failure in any two was terminal. The rapidity of these removals prevented prolonged civil war. Sri Lanka preferred frequent surgical removal to prolonged collapse.

Exile Was Often Worse Than Death

Not all kings were killed. Some were exiled or forced into monastic life. A king who became a monk ceased to exist politically. His lineage was neutralised. His supporters dissolved. His memory faded. Several rulers simply vanish from the record after abdication, their names surviving only in lists. This was a uniquely Buddhist solution to political failure. Exile did not create martyrs. It created silence. In many cases, abdication was encouraged precisely to avoid bloodshed, but the effect was the same. The ruler was removed from history.

Why the Kingdom Survived So Much Violence

The extraordinary fact is not that Sri Lanka killed its kings. It is that it survived doing so repeatedly. This was possible because the state was not embodied in the ruler. Infrastructure, monasteries, irrigation networks, and administrative memory existed independently of the throne. Killing a king did not collapse the system because the system was older and deeper than him. Kings were managers of continuity, not its source. This is why Polonnaruwa could burn, and the kingdom continue elsewhere. This is why capitals moved without destroying sovereignty. This is why Sri Lanka endured invasions that shattered other states. The king was expendable. The order was not.

Conclusion: The Most Ruthless Form of Stability

Medieval Sri Lanka solved a problem most states never did; how to remove failed rulers without destroying the state.

It did so through a calibrated system of moral judgment, elite consensus, and targeted violence. Assassination was not rebellion. It was governance. It was not a gentle system. It was, however, effective. Kings ruled magnificently, but they ruled on borrowed time. The throne was glorious, but it was never safe. And the kingdom endured precisely because no ruler was allowed to mistake himself for the state.