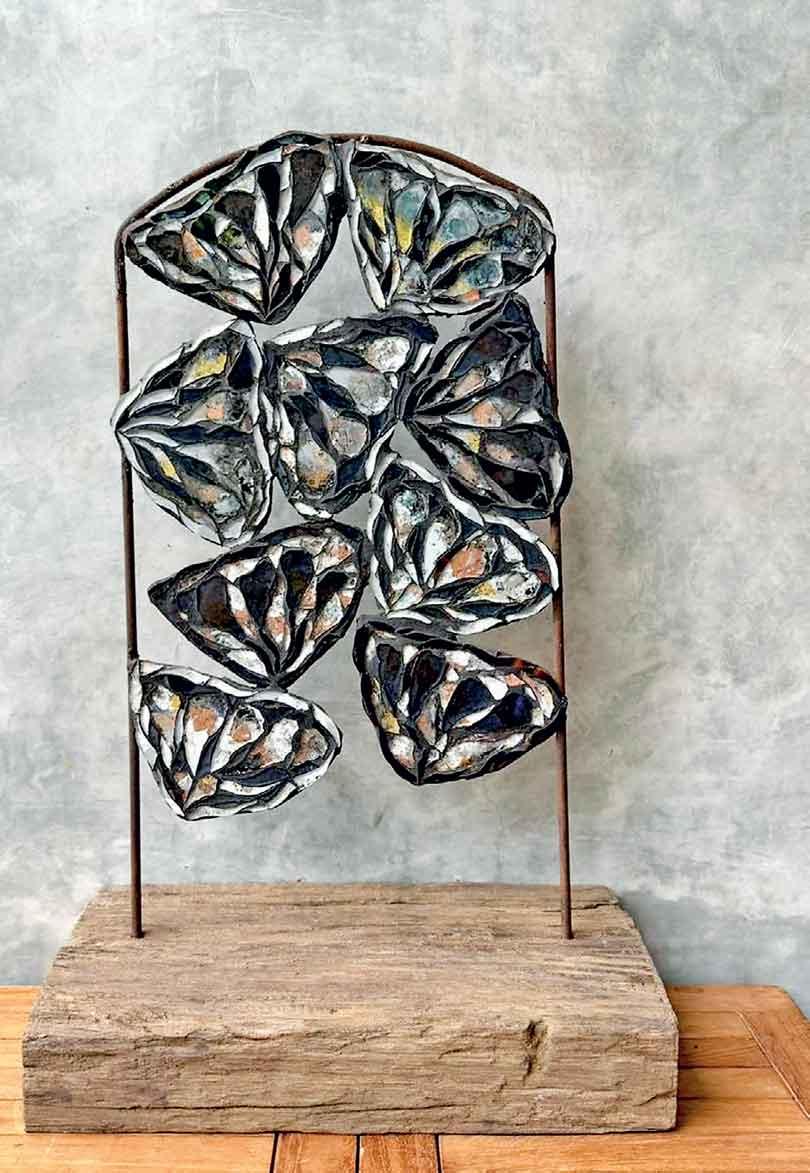

In an age obsessed with outcomes, metrics, and visibility, we rarely pause to ask what it means to persist when none of those are guaranteed. We celebrate success, but seldom examine the quiet stamina required to continue when recognition is delayed, profit uncertain, and the work itself exacts a physical toll. The story of mosaic artist Rajani Serasinghe invites us to reconsider what passion really looks like when stripped of glamour and applause.

In an age obsessed with outcomes, metrics, and visibility, we rarely pause to ask what it means to persist when none of those are guaranteed. We celebrate success, but seldom examine the quiet stamina required to continue when recognition is delayed, profit uncertain, and the work itself exacts a physical toll. The story of mosaic artist Rajani Serasinghe invites us to reconsider what passion really looks like when stripped of glamour and applause.

Rajani’s path into art was neither carefully charted nor strategically planned. With a background in interior design and a family steeped in creativity, her mother being an artist and her sister a potter, art was familiar but not predetermined. Her first mosaic emerged almost accidentally, just after her O-level examinations, when a broken windowpane (broken by Rajani while playing cricket) was transformed into a mosaic tray. Years later, with her third child only four months old, she created a mirror mosaic while seated at her mother’s dining table. When that piece, and the one that followed, sold through a business on her behalf, she found herself at the beginning of a journey she had not consciously chosen, but clearly belonged to.

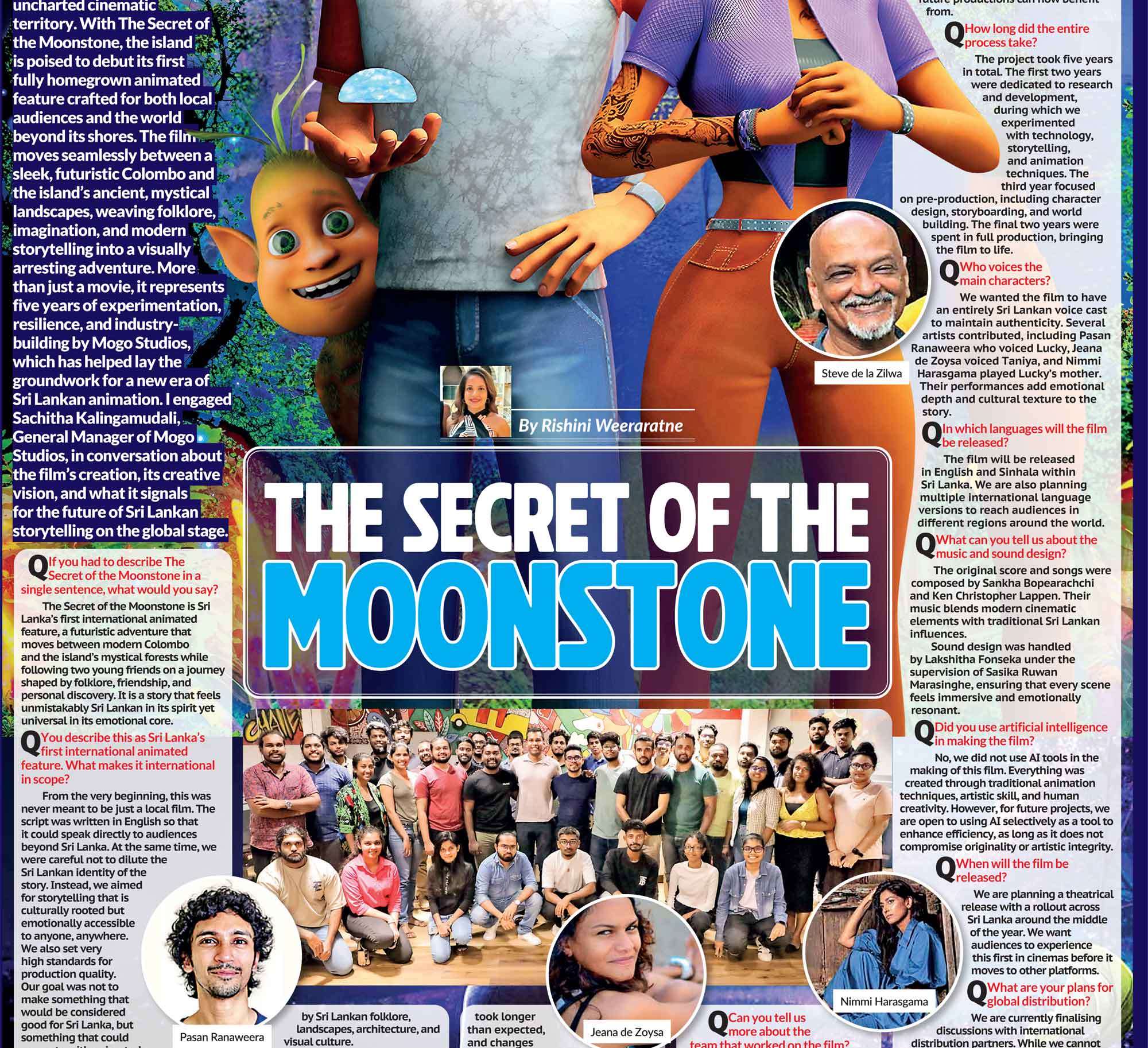

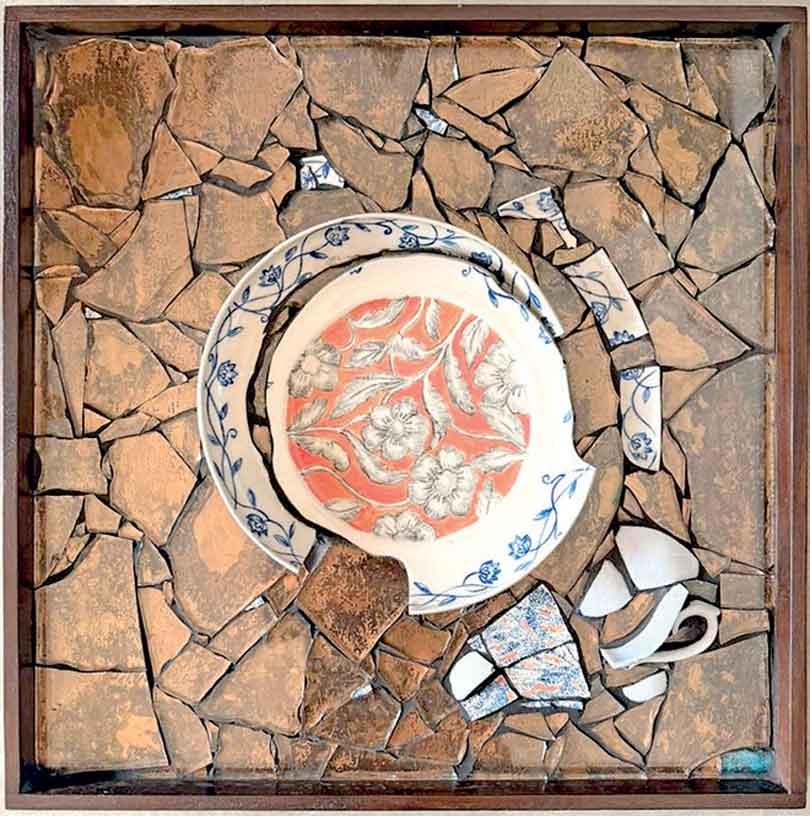

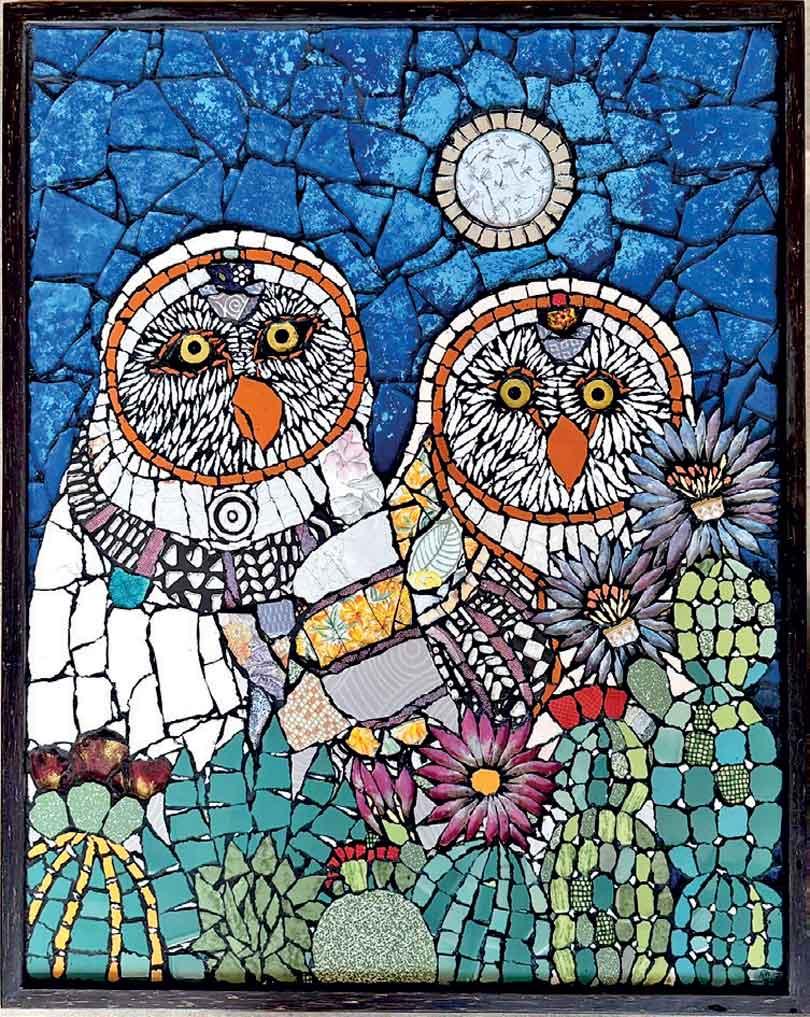

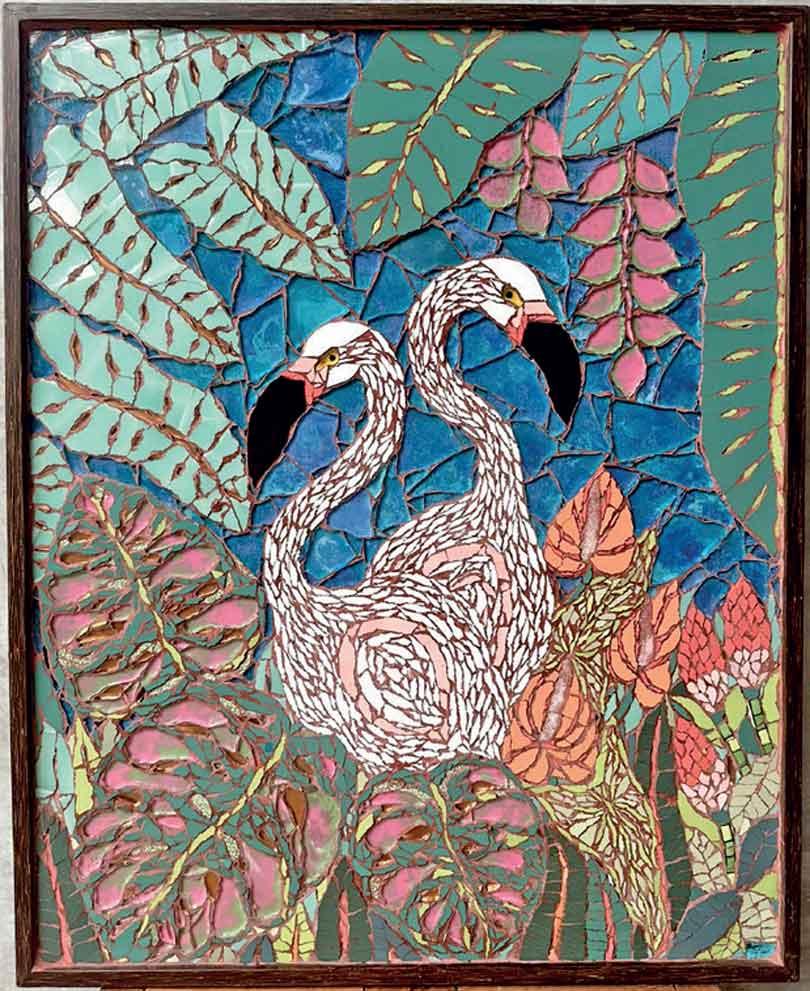

Today, Rajani specialises in mosaics using tiles and glass, repurposing broken materials and giving discarded fragments renewed meaning. For Rajani, sustainability - an incidental outcome of her process, giving her immense personal satisfaction – is as important as the act of transformation itself: the patient assembling of shards into something whole, expressive, and quietly arresting. Each tile is cut by hand so that it resembles a brush stroke, an approach that demands both technical precision and physical endurance. The work is unforgiving. Her neck and arms frequently give trouble, requiring treatment and bandaging. Despite the dust, Rajani often abandons her mask due to the heat. She works outdoors under the glare of the sun so that she can see colour accurately. This is not a romanticised studio practice. Rather, it is fatigue and labour in the truest sense.

And yet, she persists. Not because it is easy, profitable, or even always rewarding, but because something in the process compels her. That persistence becomes more striking when one considers the evolution of her themes. Early works drew heavily from nature - trees, birds, and organic forms - some prompting comparisons to Senaka Senanayake’s rainforest imagery, though realised through a vastly different medium. Over time, however, Rajani’s work shifted inward and outward simultaneously, moving from observation to interrogation.

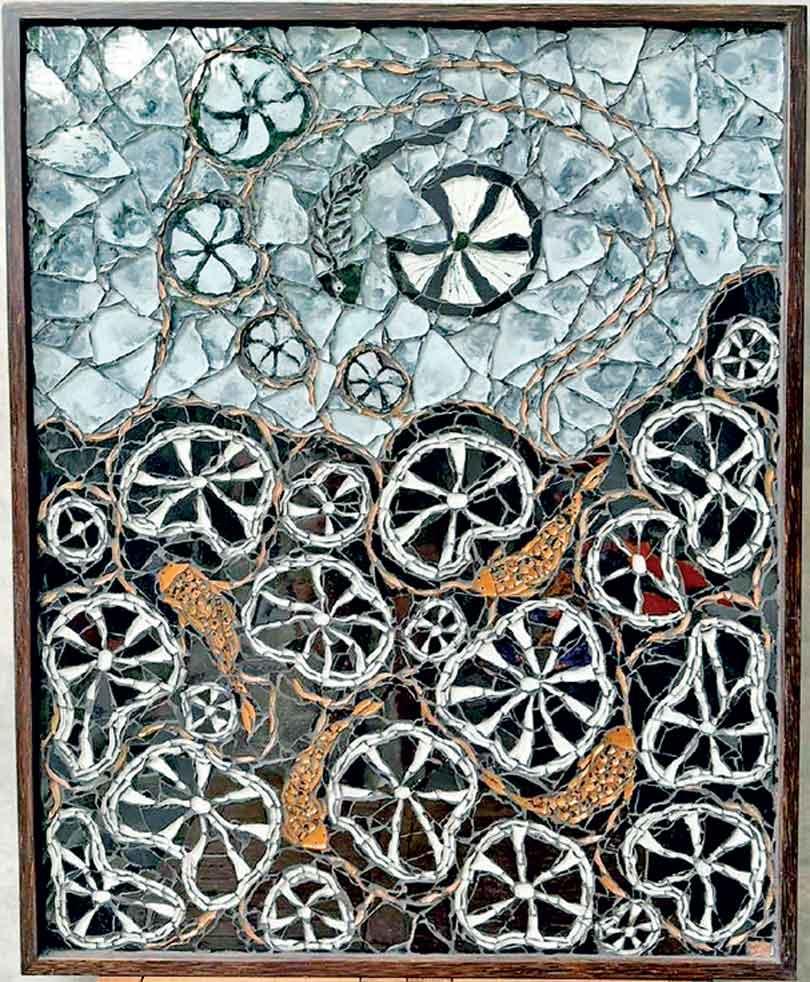

Her participation in Art Trail by ARTRA’s Impermanence exhibition marked a turning point. Working almost entirely in black and white, she explored the idea that sadness is not the opposite of happiness, but its prerequisite. Her exhibit Broken Wings, crafted from iron and glass, depicts a community of butterflies, each damaged, yet collectively beautiful and functional. It is a visual argument for interdependence, for dignity within fragility, and for the quiet strength of community.

These ideas deepened further in ARTRA’s ongoing Silenced exhibition, where Rajani confronts discrimination and displacement more directly. Married to a Tamil whose home was burnt down during Sri Lanka’s thirty-year civil war, she is acutely aware of inherited pain - pain that she says she can never fully understand yet refuses to ignore. With the exhibit Who Gets to Sit? iron and mosaic-glass chairs with broken legs ask uncomfortable questions about fairness and access. In works such as What the Room Remembers and Inventory of Absence, broken household objects evoke the remnants left behind when families flee war, disaster, or persecution. Unworn, depicting a traditional Tamil dress abandoned during evacuation, speaks of futures interrupted and childhoods suspended. While rooted in the context of war, these works resonate equally with memories of the tsunami or the more recent devastation caused by Cyclone Ditwah, reminding us that impermanence is not selective in whom it touches.

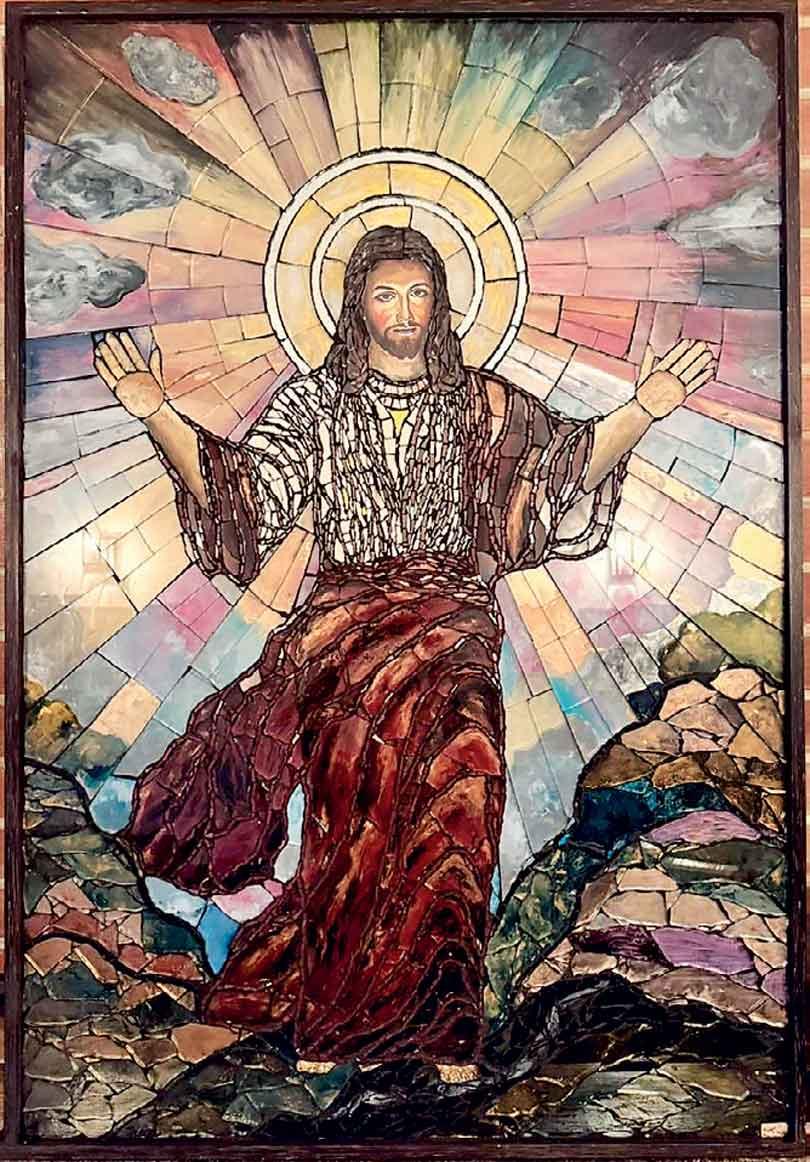

Technically, Rajani’s process mirrors the conceptual weight of her themes. She paints her glass in reverse, beginning with light and working toward darkness, anticipating the final image before it exists. Each piece must be right; if it is not, the paint is scraped away and the process begins again. This discipline reached its apex in a recent four-foot commissioned mosaic of Jesus Christ. Though painted mosaic does not typically reflect light like stained glass, Rajani spent months achieving that very effect, a painstaking pursuit that underscores her practice as a labour of devotion rather than efficiency.

Yet devotion does not shield one from disappointment. After spending three and a half months preparing her work for Impermanence, not a single piece sold. The heartbreak was real and justified. But she did not stop. She continued, returning to the workbench to produce her exhibits for Silenced, almost all of which have sold within the first few days of the exhibition’s opening.

Perhaps this is where Rajani Serasinghe’s story matters most. In a society that increasingly teaches our young people to ask, “What will this get me?”, her work quietly asks a different question: “What is this worth doing, even if it gets me nothing?” In answering it with her life, she reminds us that passion is not loud, comfortable, or always rewarded. Sometimes it is dusty, physically painful, financially uncertain, and still, profoundly necessary.