If you’re South Asian, you’ve probably been told off for wearing a crop top at least once. “Why is your stomach showing?” “Cover up.” “Is this how girls dress now?” And yet - at the same family function - an aunty walks past in a sari with a deep-neck blouse, backless tie strings, and enough confidence to shut the conversation down instantly. Apparently, midriff rules are strictly age-dependent. Younger girls get the lectures, older women get the applause - fashion has officially invented selective scolding.

Welcome to the contradiction at the heart of South Asian fashion

Welcome to the contradiction at the heart of South Asian fashion

That viral TikTok of a lehenga-crop-top combo? You’ve probably liked it, saved it for “future inspo,” or imagined wearing it to your cousin’s wedding. It’s glittery, effortless, and gives full main character energy. Skin has always been part of South Asian clothing - we just pretend it’s new when Gen Z does it.

South Asian fashion is everywhere right now. Sarees are getting sheerer, lehengas lower-rise, blouses bolder. But while the silhouettes evolve, the conversations around them haven’t always caught up. Somewhere between tradition, trend, and TikTok, meaning starts to slip.

So when culture goes viral, what exactly are we modernising - the clothes, or our understanding of them?

Crop Tops, Lehenga Fails, and Auntie Side-Eyes

Modernisation isn’t the problem - South Asian fashion has always evolved. The issue is how layered, symbolic garments are now flattened into internet-friendly formulas.

Take the viral equation: lehenga skirt + micro crop top + slick bun + chunky jhumkas + glossy makeup. It works. It reads instantly as “desi girl.” And that’s exactly the issue.

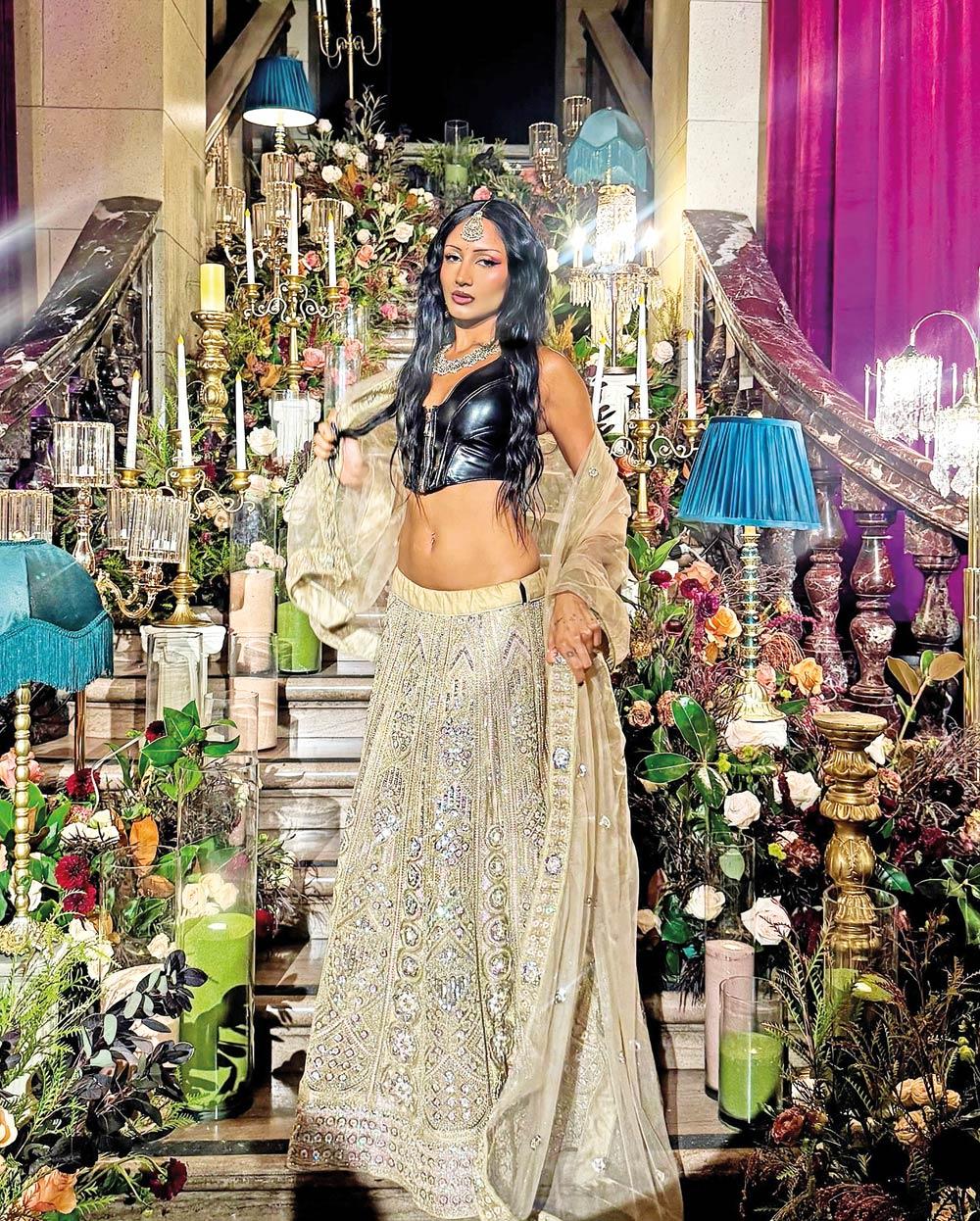

Saris are increasingly worn as wrap skirts paired with corsets, bikini tops, or bralettes, with the pallu barely draped, twisted over a shoulder, or even belted at the waist. Dupattas are no longer functional - they’re floated, tossed, wrapped around arms, or held purely for video movement. Blouses are cropped smaller, backs and fronts cut lower, and bangles are stacked like props.

The Lara Raj Diwali outfit controversy highlighted this perfectly. Her sheer lehenga, styled with a metallic silver bra, fit neatly into the desi girl aesthetic - glamorous and built for attention. But when her thong showed through the skirt, outrage followed. The backlash wasn’t about modesty; it was about styling.

Her sister, Rhea Raj, went further, swapping a traditional blouse for a cropped black leather corset - a piece that didn’t match the skirt in fabric, tone, or silhouette. The aim was edgy and cool, but the result looked more like a costume than couture.

This is where the desi girl aesthetic starts to unravel. Indian fashion elements are used less as garments and more as shorthand. Not because they reveal skin - South Asia has never shied away from it - but because the look is lifted from its system of meaning and treated as a visual moodboard.

Desi Girl Remix, Rewind, Repeat

The desi girl aesthetic has always been about remixing - the name itself comes from the song Desi Girl, where Priyanka Chopra dances in what is basically a bra, skirt, and a tiny shawl. Skin, shimmer, colour - they stay. Context, meaning, and structure - they shift. ****

The style sticks around, but the story? That sometimes slips through the cracks. When South Asian fashion goes viral, we’re not just updating garments - we’re negotiating how much of the story we carry with them.

Saris, Silks and Status Checks

Long before hashtags, South Asian clothing functioned as a visual code. What you wore signalled your region, community, marital status, wealth, and even the occasion you were attending.

In the Indus Valley, higher-class individuals often wore long robes draped over the left shoulder, leaving the right arm free - a clear display of wealth and status. These early drapes are considered one of the origins of the modern sari, showing that style and social signalling go way back.

By the Vedic period, draped garments still marked both status and practicality. Wealthy individuals wore long, flowing cloths, while lower-class people kept theirs shorter, sometimes as simple loincloths. Basically, if your drape reached the floor, you didn’t have to worry about chores - length = status.

Between the 1st and 5th centuries CE, Indian cottons and silks were global superstars. Roman writers complained that “transparent Indian cloth” - aka Jamdani muslin - was draining Rome’s wealth. Woven so fine it was called “air fabric,” owning it wasn’t just stylish - it was a flex.

Blouses weren’t purely decorative. Cropped styles helped anchor saris, balanced heavy embroidered borders, and suited tropical climates. Backless blouses with tie strings offered flexibility - essential before ready-made sizing.

Accessories carried meaning, too. The bindi, before it became a sticker trend, was a red dot between the eyebrows, symbolising the opening of the third eye and spiritual protection. Jhumkas, the bell-shaped earrings, weren’t just for jingling - their sound was thought to ward off negative energy, while their shape represented fertility, abundance, and spiritual awareness.

Regional textiles were also codes. Kanjeevaram silk marked temple rituals and weddings, Bandhani tie-dye celebrated marriage, and Kantha embroidery stitched stories into old cloth long before anyone called it “upcycling.”

Lehengas and ghagras became ceremonial must-haves between the 10th and 16th centuries. High waistlines encouraged upright posture in rituals, and embroidery hugged hems and panels because those areas were most visible in motion. Colour had a language too: white for mourning, red for marriage, yellow for new beginnings. Every outfit told a story - your life stage, your role, even your intentions - without a word.

This is also when South Asian fashion started getting labelled “ceremonial” or “traditional,” as if it couldn’t evolve. But as soon as colonial influence hit - not just in India, but across South Asia - daily draped garments were swapped for Western clothing, and the styles we once wore every day were relegated to rituals and special occasions. Even then, “traditional” didn’t stay still - it got its own mini revamp.