How Policy Paralysis Is Ceding Sri Lanka’s Maritime Crown

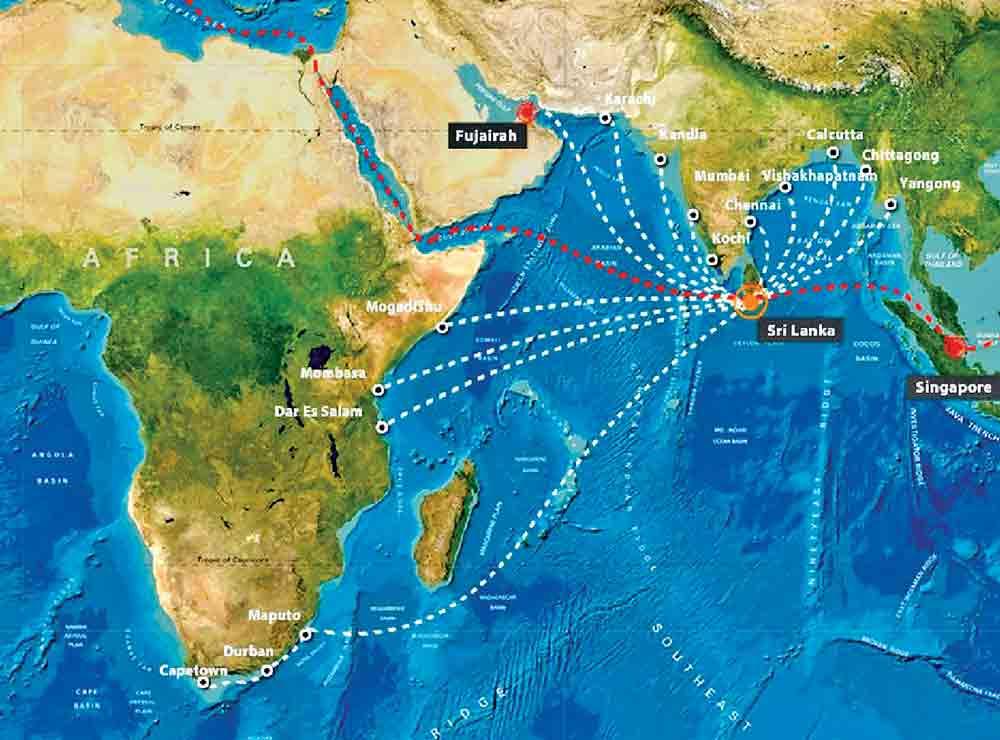

In the high-stakes theatre of the Indian Ocean, there is no such thing as a vacuum. Maritime strategists have long argued that when one state hesitates, another inevitably moves in. For Sri Lanka, situated at the literal crossroads of global trade, that warning is becoming reality. Persistent policy indecision is steadily eroding what should be a natural advantage, converting it into a gift for regional competitors.

At the centre of this problem is Sri Lanka’s failure to finalise Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for foreign research vessels. In the parliamentary debates and media briefings, senior officials have admitted that the absence of a sound vetting framework resulted in a general moratorium on such vessels. While masquerading as a security measure, the ban has become increasingly more emblematic of institutional paralysis. While Colombo deliberates, ports in India expand, Singapore consolidates its dominance, and even the Maldives absorbs opportunities Sri Lanka declines.

The Law of the Maritime Vacuum

Maritime economics follows a simple rule: ships, cargo, and capital do not wait. UNCTAD and International Maritime Organization data show that during the 1980s and 1990s, delays in expanding Colombo Port’s container capacity coincided with Singapore’s rapid rise as a global mega hub, combining geography with technology, regulatory certainty, and decisive governance. In the following decades, India invested heavily in Jawaharlal Nehru Port (Mumbai) and Kochi, deliberately reducing dependence on Colombo as a transshipment centre, according to Indian port authority reports.

That same pattern is now visible in research and port-call sectors. When Sri Lanka denied entry to the Chinese research vessel Xiang Yang Hong 03, AIS vessel-tracking data showed it subsequently docked in the Maldives. Port industry sources estimate that a single research or naval port call can generate USD 800,000 – 1 million in revenue through port fees, bunkering, provisioning, and services. The opportunity was not eliminated but it was relocated.

The Economic Cost of Saying “No”

Beyond individual cases, cumulative losses are significant. Shipping agents and port-sector sources estimate that Sri Lanka normally receives 20–30 foreign research and naval port calls annually. Each visit supports fuel suppliers, food and water provision, waste management, ship repairs, chandlery services, hotels, transport providers, and local employment.

Using conservative industry estimates, the moratorium and regulatory uncertainty could cost Sri Lanka USD 15–25 million per year in direct and indirect maritime services revenue. These figures are consistent with port revenue data from the Maldives, Oman, and Djibouti, which report earnings from similar vessel visits. This does not include longer-term losses such as reduced repeat visits, lower investor confidence, or missed opportunities to develop Colombo and Hambantota as specialised support hubs. For a country facing foreign exchange constraints, this is revenue foregone not due to global conditions, but domestic indecision.

The Price of a Pause

The most damaging casualty of this paralysis was the cancellation of the UN-flagged Dr. Fridtjof Nansen survey. Operated under the UN and the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research; the vessel was scheduled to assess Sri Lanka’s fish stocks and marine ecosystems. UN-affiliated fisheries officials confirmed that the mission was abandoned due to regulatory uncertainty rather than security concerns.

The immediate loss was financial, but the deeper cost was strategic. According to UN agencies, a comparable survey may not be possible again until after 2030, depriving policymakers and coastal communities of reliable data for nearly a decade.

A Familiar Regional Pattern

This episode fits a long-standing trend. Following the mid-2000s reversal of trade liberalisation and the reintroduction of para-tariffs, UNCTAD data shows manufacturing and export investment shifted toward Vietnam and Malaysia. Investor surveys and business press reporting consistently cited policy inconsistency as a decisive factor.

Today, the moratorium reflects the same institutional weakness. While Sri Lanka hesitates, India has implemented clear regulatory frameworks for foreign maritime activity, and the Maldives has positioned itself as a service-friendly port-of-all destination without framing engagement as a geopolitical dilemma.

From Strategic Hub to Strategic Bystander

Geographically, Sri Lanka occupies one of the most valuable maritime positions in the world. Located just six to ten nautical miles north of one of the planet’s busiest shipping lanes, the island sees nearly 60,000 vessels pass annually, according to international maritime traffic estimates. Analysts and port economists have long argued that Sri Lanka should have become the “Singapore of South Asia” - comprehensive maritime services hub combining ports, logistics, research support, bunkering, and predictable regulation. That transformation never materialised. Instead, Sri Lanka’s maritime strategy has been constrained by static non-alignment, which is an ideological rigidity equating decisive governance with geopolitical alignment. This mindset has produced a negative default, where saying “no” to everyone is mistaken for neutrality, and regulatory absence is treated as strategic caution. Non-alignment was never meant to be passive. Strategic autonomy is achieved not by avoiding decisions but by setting rules and enforcing them consistently, regardless of the flag a vessel flies. Singapore did not become a maritime superpower by avoiding geopolitics; it did so by building institutions strong enough to manage them. Sri Lanka’s failure has been a failure of governance, not geography.

From Paralysis to Pragmatism

Sri Lanka does not need blanket bans; it needs institutional clarity. Maritime experts recommend a differentiated framework. Scientific research vessels could be admitted under transparent conditions, including mandatory data-sharing, Sri Lankan scientific participation onboard, and oversight by national authorities. Naval and logistical port calls could be managed as regulated services, with the Sri Lanka Navy enforcing strict prohibitions on unauthorised surveillance. Such measures would not dilute sovereignty; they would operationalise it. Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone is nearly eight times the country’s landmass, according to official maritime boundary data, it is one of its most valuable assets. Yet hesitation has turned this advantage into a liability. In maritime affairs, opportunity is finite. When it is not used decisively, it is inevitably captured elsewhere. Sri Lanka can no longer remain the passive anvil of the Indian Ocean. The choice facing policymakers is no longer between alignment and neutrality, but between governance and drift.