“Sustainability is old, and it is forever. If we don’t learn how to be sustainable, it’s not the planet that dies. It’s the human race.”

Sustainability is often spoken about as if it were a trend. Something newly invented. Something to be adopted, rebranded, or abandoned when it stops selling. Yet sustainability predates marketing departments, supply chains, and certification labels. It is how humans lived for most of history. Repairing. Reusing.

Respecting limits. Understanding seasons. Knowing that resources were finite, and that effort mattered. Long before sustainability became a buzzword, it was simply a way of life. At some point, sustainability became a product. The fashion industry, in particular, loves solutions it can sell. So, sustainability was reduced to materials. Polyester was replaced with organic cotton. Virgin nylon was swapped for recycled fibres. Green hangtags appeared. Sustainability reports were published. “Conscious” collections were launched. These changes are not meaningless, but they are incomplete.

Respecting limits. Understanding seasons. Knowing that resources were finite, and that effort mattered. Long before sustainability became a buzzword, it was simply a way of life. At some point, sustainability became a product. The fashion industry, in particular, loves solutions it can sell. So, sustainability was reduced to materials. Polyester was replaced with organic cotton. Virgin nylon was swapped for recycled fibres. Green hangtags appeared. Sustainability reports were published. “Conscious” collections were launched. These changes are not meaningless, but they are incomplete.

When sustainability becomes something, you buy rather than something you practise, it loses its power. A garment made from organic cotton but worn twice and discarded is not sustainable. A recycled fabric produced at scale, sold cheaply, and replaced the following season is not progress. We have mistaken input changes for behavioural change. The uncomfortable truth is that the fashion industry cannot continue producing at its current pace and call itself green, regardless of the fabric it uses.

The real issue is pace.

Sustainability conversations often avoid the hardest question of all. How much is enough?

The global fashion industry produces more than one hundred billion garments every year for a population of just over eight billion people. This equation does not improve with better materials. Overproduction cannot be offset by good intentions. If volume stays the same or continues to grow, environmental harm is only delayed, not reduced. Water use, chemical processing, energy consumption, transport emissions, and labour pressure all scale with quantity. Yet production volume is rarely addressed, because slowing down challenges growth models, profit forecasts, and investor expectations. It is far easier to change the fibre than to change the system.

Sustainability was never about fabric alone.

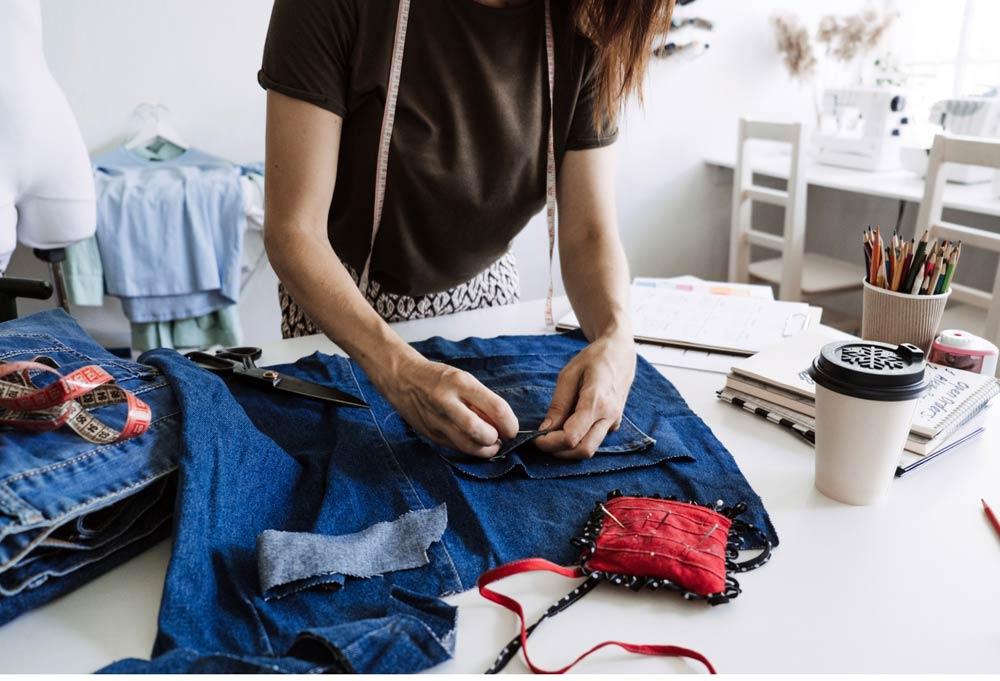

Our ancestors did not describe their lives as sustainable. They simply lived within their means. Clothes were valued because they required time and labour. Fabric was expensive. Making something last was not a moral choice. It was a practical one. Garments were repaired because replacing them was costly. Clothes were passed down, altered, and reworked. Ownership came with responsibility. Today, the opposite is true. Clothing is cheaper than ever, and meaning is thinner than ever. We have wardrobes full of clothes and nothing to wear, not because we lack options, but because we lack connection. This is where sustainability truly begins. Not in the fibre, but in the relationship.

One of the greatest misconceptions around sustainability is that it demands deprivation. That buying less means joyless wardrobes and constant self-policing. In reality, buying less often leads to more satisfaction. When you buy with intention, you choose garments that fit your life rather than fleeting trends. You learn what you actually wear. You invest in quality. You develop a personal style instead of chasing novelty. Buying better is not only about price. It is about construction, versatility, repairability, and relevance to your lifestyle. Keeping clothes longer is not about nostalgia. It is about respect for resources, labour, and your own money. This shift is not anti-fashion. It is anti-waste.

Greenwashing thrives because it soothes discomfort.

The industry knows consumers care, and that concern has become a marketing opportunity. Words like eco-friendly, conscious, and responsible are everywhere, often stripped of meaning. They comfort us without asking anything of us. They allow consumption to continue at the same pace with a clearer conscience. True sustainability is uncomfortable. It asks brands to produce less. It asks consumers to pause before purchasing. It asks us to sit with desire instead of immediately satisfying it. That discomfort is not failure. It is honesty.

Sustainability is not trendy, and that is precisely the point.

Sustainability is not trendy, and that is precisely the point.

Trends rise and fall. Sustainability does not have that luxury. Calling it “in” or “out” misunderstands its nature. Sustainability is not a look, a colour palette, or a seasonal theme. It is a condition for survival. If we do not learn to live within ecological and social limits, the planet will continue, altered and harsher, but humanity will struggle. This is why sustainability cannot be seasonal. It cannot be optional. And it cannot be reduced to marketing language. If sustainability is forever, then the work ahead is slow, unglamorous, and deeply personal. It looks like asking whether you need something before buying it. Learning basic repair skills. Supporting small producers who make fewer, better things. Valuing craftsmanship over speed. Accepting that not every desire needs to be met instantly or cheaply.

It looks like letting clothes age. Letting them soften. Letting them hold memory. A garment that lasts is not one that never changes, but one you continue to choose. Sustainability is not new. It is not trendy. And it is not something we can outsource to brands alone. It is a shared responsibility rooted in how much we produce, how much we buy, and how long we keep what we own. The fashion industry can innovate endlessly, but without restraint, innovation becomes distraction. Without relationship, sustainability becomes performance. Beyond the seams of our clothes lies a question we can no longer avoid. Not what are we wearing, but how are we living? As we step into a new year, perhaps this is the moment to redefine what fashion truly is. Not a constant chase for the new, but a considered relationship with what we choose to wear.