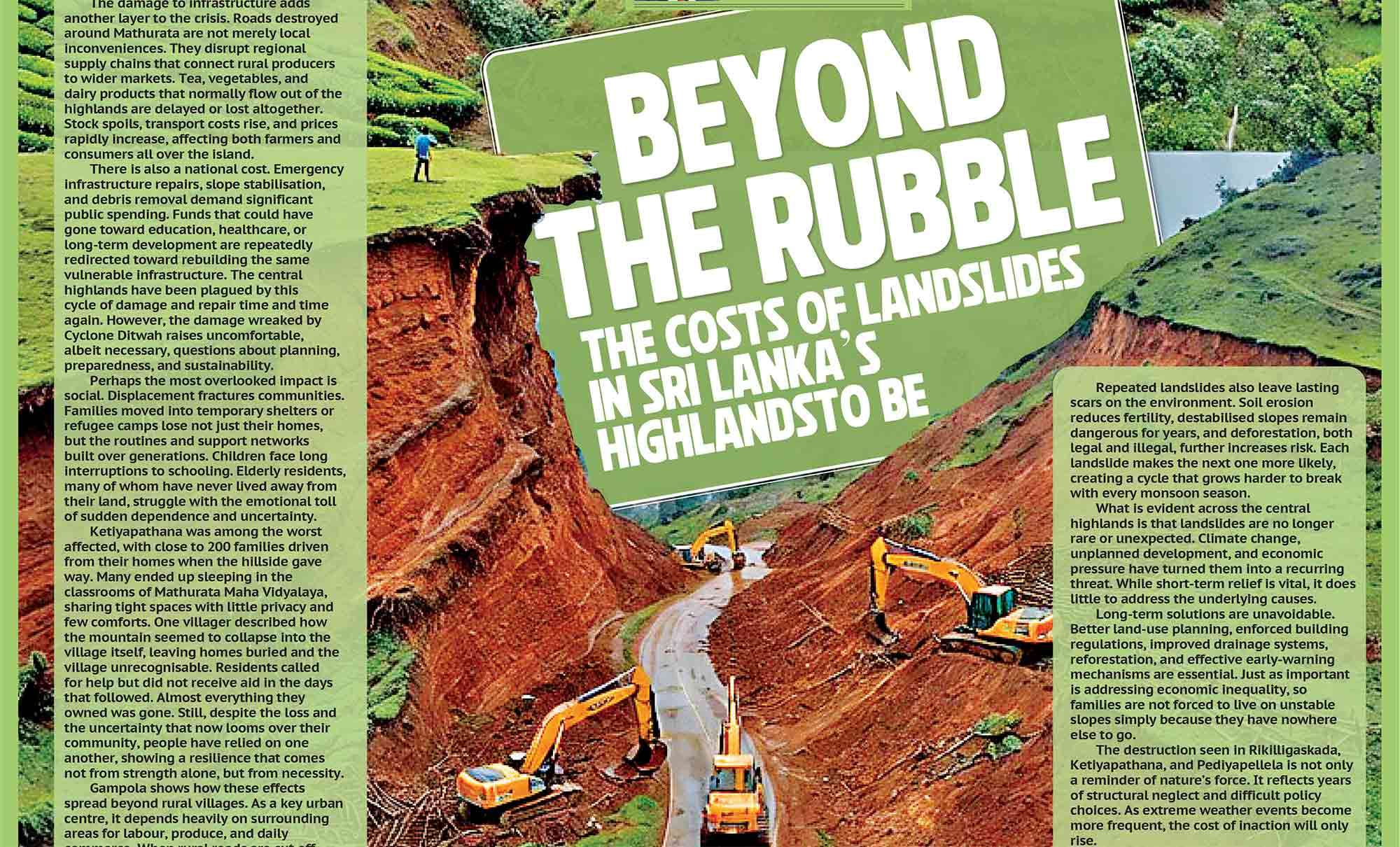

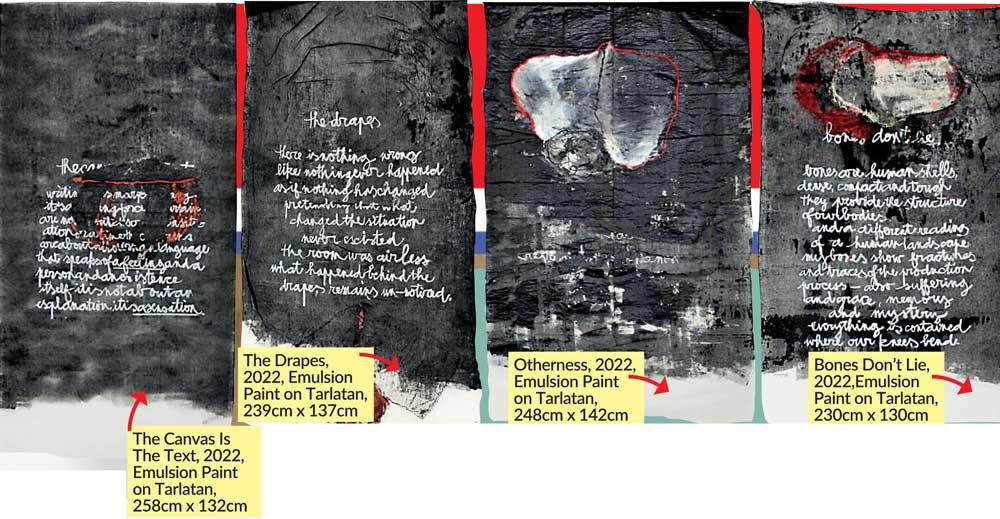

Bones Don’t Lie, 2022, Emulsion Paint on Tarlatan, 230cm x 130cm Bones Don’t Lie is an extremely powerful drape, the final answer. It carries you to the utter depths of the earth and stays with you. It reminds us that humans are complex and complicated. The work evokes sensation. The curtains carry lines of text inviting viewers into another place, their inner place. This connection creates bridges between worlds. At the end of the day, we are all alike.

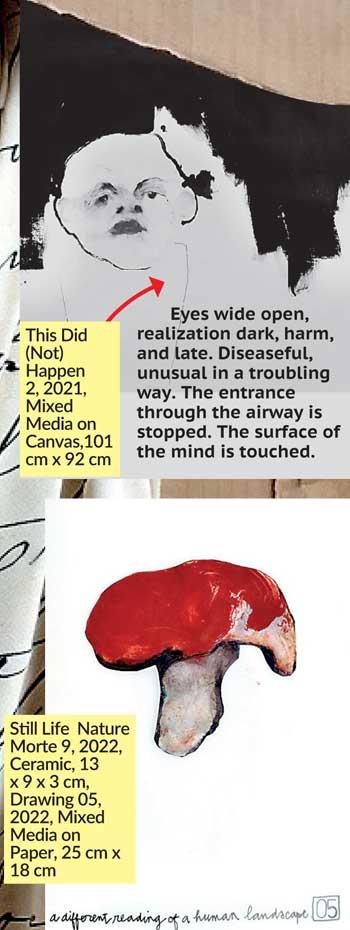

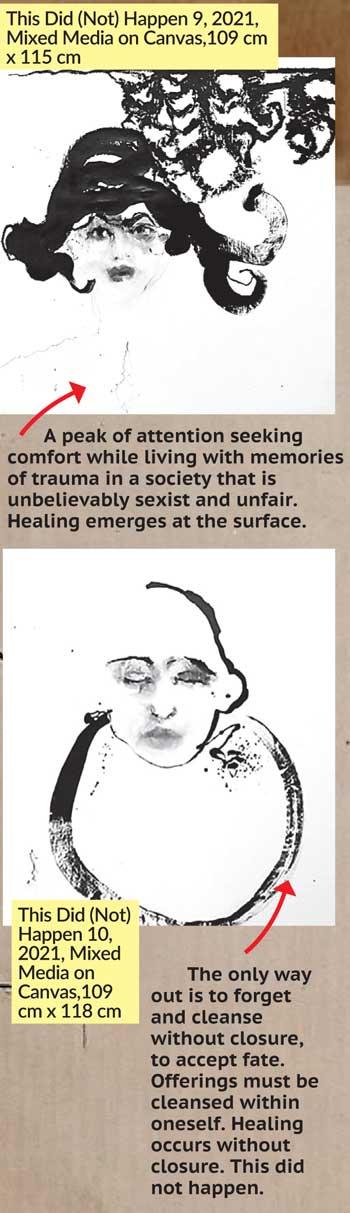

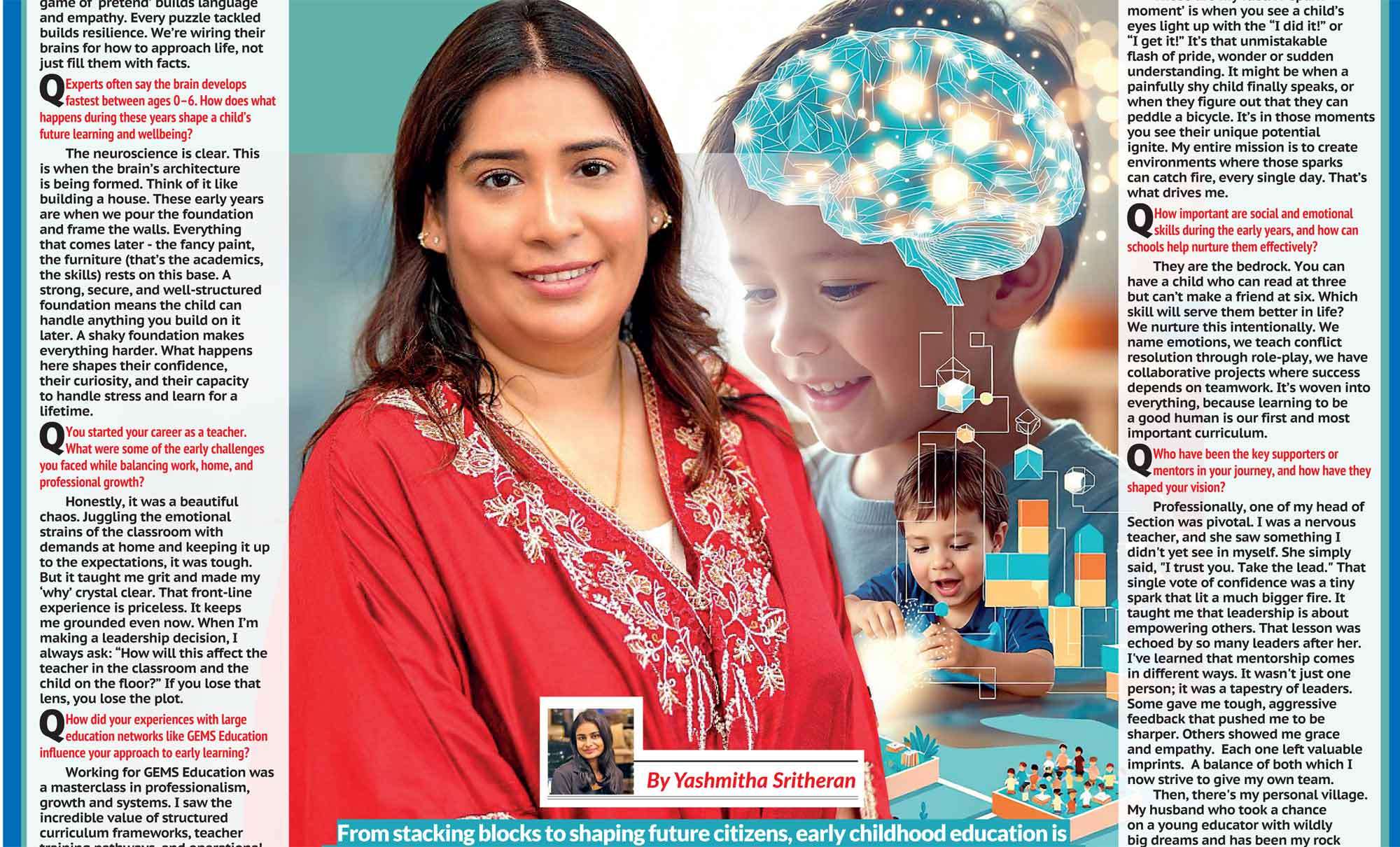

Fabienne Francotte’s Still Life | Nature Morte moves with the quiet insistence of memory. It does not dramatize trauma or offer consolation. Instead, it dwells in what remains after the storm, tracing the subtle impressions that pain leaves on the body and the psyche. The exhibition asks the viewer to slow down, to inhabit spaces of absence and invisibility, to witness the unspeakable without the need for closure. Francotte’s practice is shaped by precision and discipline. Calligraphy and classical dance under Maurice Béjart have left their mark in the careful modulation of line, gesture, and rhythm. Yet the work resists formal constraint. It flows from encounter and intuition. Over the past twenty years, Francotte has worked with people living on the margins; psychiatric patients in Angoda, children in development centers, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, and troubled youth in Belgium. Drawing becomes a shared language, a space of release, a means of transmitting what words cannot hold. She opens spaces. In a world dulled to suffering, her work demands presence, attention, and care. Still Life | Nature Morte is not spectacle but reflection. It is a meditation on the human condition, a recognition of our shared fragility, and a testament to the ways the body endures, remembers, and holds what the world often refuses to see.

Fabienne Francotte’s Still Life | Nature Morte moves with the quiet insistence of memory. It does not dramatize trauma or offer consolation. Instead, it dwells in what remains after the storm, tracing the subtle impressions that pain leaves on the body and the psyche. The exhibition asks the viewer to slow down, to inhabit spaces of absence and invisibility, to witness the unspeakable without the need for closure. Francotte’s practice is shaped by precision and discipline. Calligraphy and classical dance under Maurice Béjart have left their mark in the careful modulation of line, gesture, and rhythm. Yet the work resists formal constraint. It flows from encounter and intuition. Over the past twenty years, Francotte has worked with people living on the margins; psychiatric patients in Angoda, children in development centers, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, and troubled youth in Belgium. Drawing becomes a shared language, a space of release, a means of transmitting what words cannot hold. She opens spaces. In a world dulled to suffering, her work demands presence, attention, and care. Still Life | Nature Morte is not spectacle but reflection. It is a meditation on the human condition, a recognition of our shared fragility, and a testament to the ways the body endures, remembers, and holds what the world often refuses to see.

QStill Life | Nature Morte centers on what remains after trauma rather than the trauma itself. When you look back at this body of work, what do you feel has remained the most for you?

QStill Life | Nature Morte centers on what remains after trauma rather than the trauma itself. When you look back at this body of work, what do you feel has remained the most for you?

First, all the sensations I felt when meeting the many Sri Lankans around a drawing table expressing themselves. They remained silent, but I could feel the many layers of pain and sadness; untold, unspoken. While working on this exhibition Still Life – Nature Morte, I processed these drapes, inviting the viewer to be The Other and to speak about their own invisible wounds and hidden traumas.

QMuch of your process relies on non-verbal communication. In a world obsessed with explanation and articulation, what has silence taught you about human connection?

Massive information. While words convey information, the body opens doors. Through posture, breath, and individual attention, we reveal our inner topographies; the fragile places where emotions reside, often too complex to articulate. Silence, stillness, is a territory without risk or intrusion. It connects rather than separates.

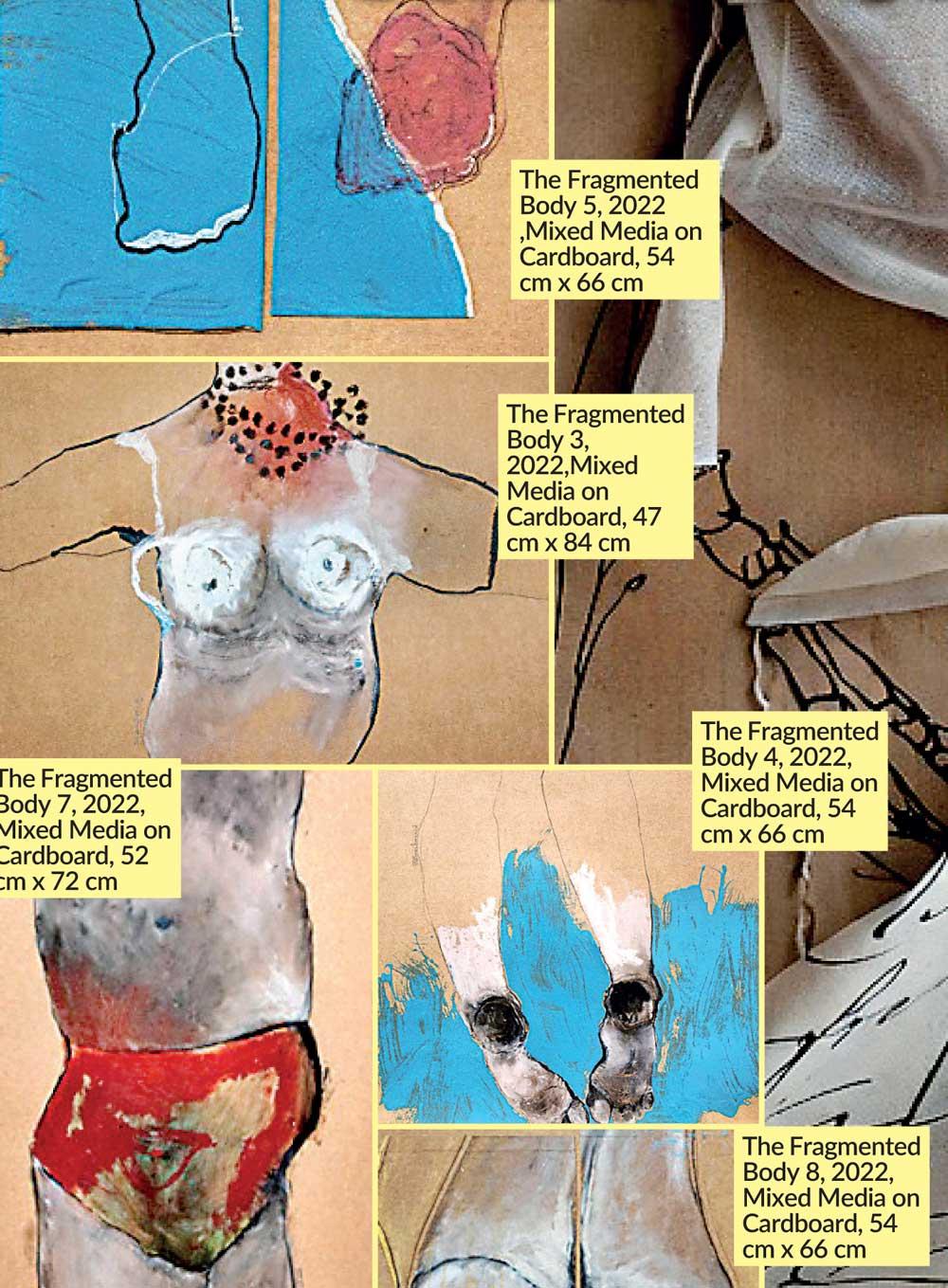

QThe body appears fragmented, restrained, and yet resilient in works like The Fragmented Body and Bones Don’t Lie. How do you personally understand the body as a site of memory, survival, or resistance?

The body is an inner topography. It gives us a panoramic view of our past. The Fragmented Body is a series on brown cardboard sheets showing disembodied segments of male and female bodies. The arms, legs, and torsos carry a darker story of violence, hurt, and mutilation.

The fragmented body fills an existential human deficit. They are intimate, vulnerable protagonists; that’s what makes a human, human!

QYour practice draws from calligraphy and classical dance, both disciplines rooted in control and precision, yet your current work feels instinctive and raw. How did you learn to trust your subconscious in making art?

QYour practice draws from calligraphy and classical dance, both disciplines rooted in control and precision, yet your current work feels instinctive and raw. How did you learn to trust your subconscious in making art?

I didn’t. I couldn’t escape the connection between my brain and my hand. I am self-taught, started to draw when I was 42, and expressing myself was an urgent necessity. What helps the whole “magical” process of having access to the subconscious are the many diaries I wrote and collected since 1972. Today I have more than 100 books where the many chapters of my life are recorded.

QYou’ve described yourself as an “unintentional conduit of the soul.” After two decades of practice, do you feel art has healed you as much as it has allowed others to release something within themselves?

I am sure art played a great role. It invited me not only to record my emotions but also to share them with others. I never thought I could be an artist. Everything can happen, and we don’t need to have special skills to express ourselves. It is the way we look at things that makes us become artists. And after two decades I came to the conclusion that I draw what I saw, not what I see.

QYou spend so much time holding space for other people’s pain. How do you take care of yourself after absorbing so many heavy stories?

I don’t think much about it; it is a kind of immediate reaction to go and bring a bubble to people who felt leftovers. While doing something for others, we also feel happiness. I must admit, when the drawing session is over and I am on my way home, I am empty and absent-minded. But I never feel bad. I just need to rest.

QWhen viewers stand in front of works like The Curtains or Bones Don’t Lie, what do you hope they feel before they begin to analyze?

A sensation. The curtains carry lines of text inviting them to another place, their inner place. This connection is crucial; it creates bridges between worlds. At the end of the day, we humans are all alike.