Gandhi’s Complex Legacy The Untold Story Behind His Celibacy Experiments

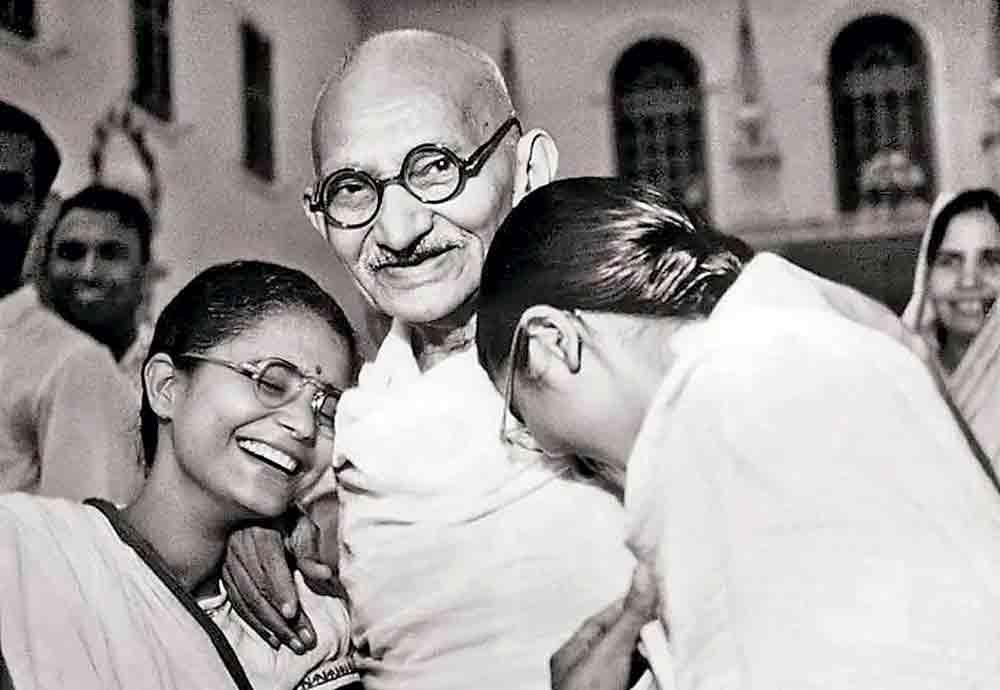

Mahatma Gandhi is remembered around the world as the guiding force behind India’s independence. He is celebrated not just for freeing a nation from colonial rule, but for doing so through peace, nonviolence, and moral conviction. His ideas inspired many global movements for justice, and his name remains synonymous with truth and courage. Yet behind the public figure was a deeply personal journey, and some of the most intimate parts of Gandhi’s life still raise difficult ethical questions.

Among the most controversial aspects of Gandhi’s personal life was his lifelong commitment to brahmacharya, a form of spiritual celibacy. This practice, which Gandhi considered central to his moral and spiritual strength, involved complete abstinence from sexual activity. But in his later years, Gandhi’s methods of maintaining celibacy came under scrutiny. His practice of sleeping beside young women, including relatives and close followers, in order to test his self-control, is today seen by many as ethically troubling.

While Gandhi insisted that these practices were spiritual experiments, not sexual encounters, the implications of his choices continue to provoke debate. These private actions are now being re-examined through the lens of modern understandings of gender, power, and consent. The result is a more complex and honest evaluation of a man who is often placed on a pedestal, but who was also deeply human.

Gandhi believed that the ideal of brahmacharya went beyond physical abstinence. It meant freedom from all forms of desire, including sexual thoughts. He saw self-control as a foundation of strength, both spiritual and moral. To test his progress on this path, Gandhi chose to place himself in what he considered challenging situations. He argued that if he could remain pure in the presence of young women without experiencing temptation, he would have achieved a higher level of spiritual discipline.

In the 1940s, Gandhi began a series of what he described as experiments in celibacy. He would share sleeping spaces with young women, sometimes naked or semi-naked, including his grandniece Manu Gandhi and other devoted followers. These women were often teenagers or in their early twenties, while Gandhi was in his seventies. Gandhi maintained that these experiments were entirely nonsexual and that his intentions were purely spiritual. He documented his experiences and defended his actions as part of his journey toward inner purity.

For Gandhi, these tests were not immoral because he claimed he did not act on any desire. He believed the practice was not about suppression, but about confronting temptation and proving mastery over it. He saw no harm in what he was doing because he was not engaging in any physical relationship, and he considered the act of overcoming desire in such settings to be a measure of personal victory.

However, even during Gandhi’s lifetime, his celibacy experiments were questioned by friends and political colleagues. Some expressed concern privately, while others feared the potential damage to his public reputation and the independence movement. Figures like Vallabhbhai Patel and C. Rajagopalachari urged him to end the practice. Nevertheless, Gandhi continued, confident in the purity of his intentions.

Today, many historians and scholars view these practices with concern. The main issue lies not in Gandhi’s stated aim, but in the methods, he used and the effect they may have had on the young women involved. These women were not just participants in his spiritual experiments. They were his relatives, his followers, and in many cases, his disciples. The enormous power and influence Gandhi held over them cannot be ignored.

Consent in such situations becomes complicated. When someone is seen as a moral guide, a political hero, and a father figure, disagreeing or refusing a request may not feel like a real option. The women involved may have respected and trusted Gandhi deeply. But that trust, in such a context, can create emotional pressure and moral confusion. They may have believed they were participating in something noble, even if it made them uncomfortable. Or they may have felt they could not say no without disappointing someone they considered a spiritual leader.

From a modern perspective, consent is more than just verbal agreement. It includes freedom from coercion, pressure, or emotional manipulation. In situations where one person holds overwhelming power over another, even unspoken expectations can feel like commands. Today, we understand much more about how unequal relationships can affect someone’s ability to make fully free and informed choices.

We also now recognise the psychological impact that such experiences can have, particularly on young women. Being placed in situations of moral uncertainty, especially with someone they admire and trust, can lead to long-lasting emotional confusion. While Gandhi may have believed he was teaching discipline and self-control, the emotional toll on those involved cannot be dismissed.

It is important to acknowledge that Gandhi did not try to hide these practices. He wrote about them openly and allowed others to question him. For him, living truthfully meant being transparent, even when his actions were controversial. He did not believe he was doing anything wrong and defended his choices as part of his spiritual development.

Yet the power he held, both in public life and within his personal circle, makes the situation ethically complex. Gandhi may have been sincere in his intentions, but the impact of his actions must be considered not just from his point of view, but also from the perspective of the young women involved. Their agency, emotions, and autonomy matter just as much as his spiritual goals.

This is where modern ethics plays a crucial role in shaping our understanding of historical figures. In Gandhi’s time, questions of power imbalance and psychological harm were not widely discussed. Today, however, we are far more aware of how emotional pressure can influence personal choices, especially in relationships where trust and reverence are involved. This makes it essential to revisit the past with fresh eyes and deeper empathy for all those involved.

Critics of Gandhi’s celibacy experiments argue that these actions must be seen not just in terms of spiritual intent, but in light of their effect on vulnerable individuals. They point out that Gandhi, despite his moral teachings, may have overlooked how his methods could confuse, distress, or emotionally impact the women who trusted him. In doing so, they call for a more complete and honest understanding of his life.

Supporters of Gandhi’s philosophy argue that his work in fighting injustice, promoting nonviolence, and serving the poor should not be overshadowed by these personal controversies. They see his experiments in celibacy as an extension of his deep commitment to truth and self-discipline. For them, Gandhi’s life was a continuous struggle against weakness, and his personal choices were part of his spiritual quest.

The truth, however, is likely to be more nuanced. Gandhi’s greatness as a leader is beyond doubt. His influence on the course of history is undeniable. But like all human beings, he had flaws. His intentions may have been pure, but the consequences of his actions were complex. To recognise this is not to diminish his legacy, but to understand it more fully.

By acknowledging both Gandhi’s visionary leadership and the ethical questions surrounding his personal practices, we embrace a more balanced view of history. We move beyond worship and criticism and instead look at the full human picture. We honour his achievements while learning from his mistakes.

In doing so, we also uphold the values Gandhi himself believed in. He taught the world the importance of self-reflection, of questioning authority, and of searching for truth, even when it is uncomfortable. To examine his life honestly is, in many ways, to follow his example.

Gandhi’s legacy remains one of the most powerful in modern history. His message of peace, nonviolence, and social justice continues to inspire millions. But exploring the more controversial aspects of his personal life adds depth to our understanding of him. It reminds us that even the most revered leaders are not beyond reproach. They are human, with struggles and contradictions, just like anyone else.

In recognising both the light and the shadow in Gandhi’s life, we foster a culture that values truth and transparency. We create space for growth, learning, and meaningful reflection. And we remind ourselves that true leadership includes not only public service, but also the courage to confront one’s own imperfections.