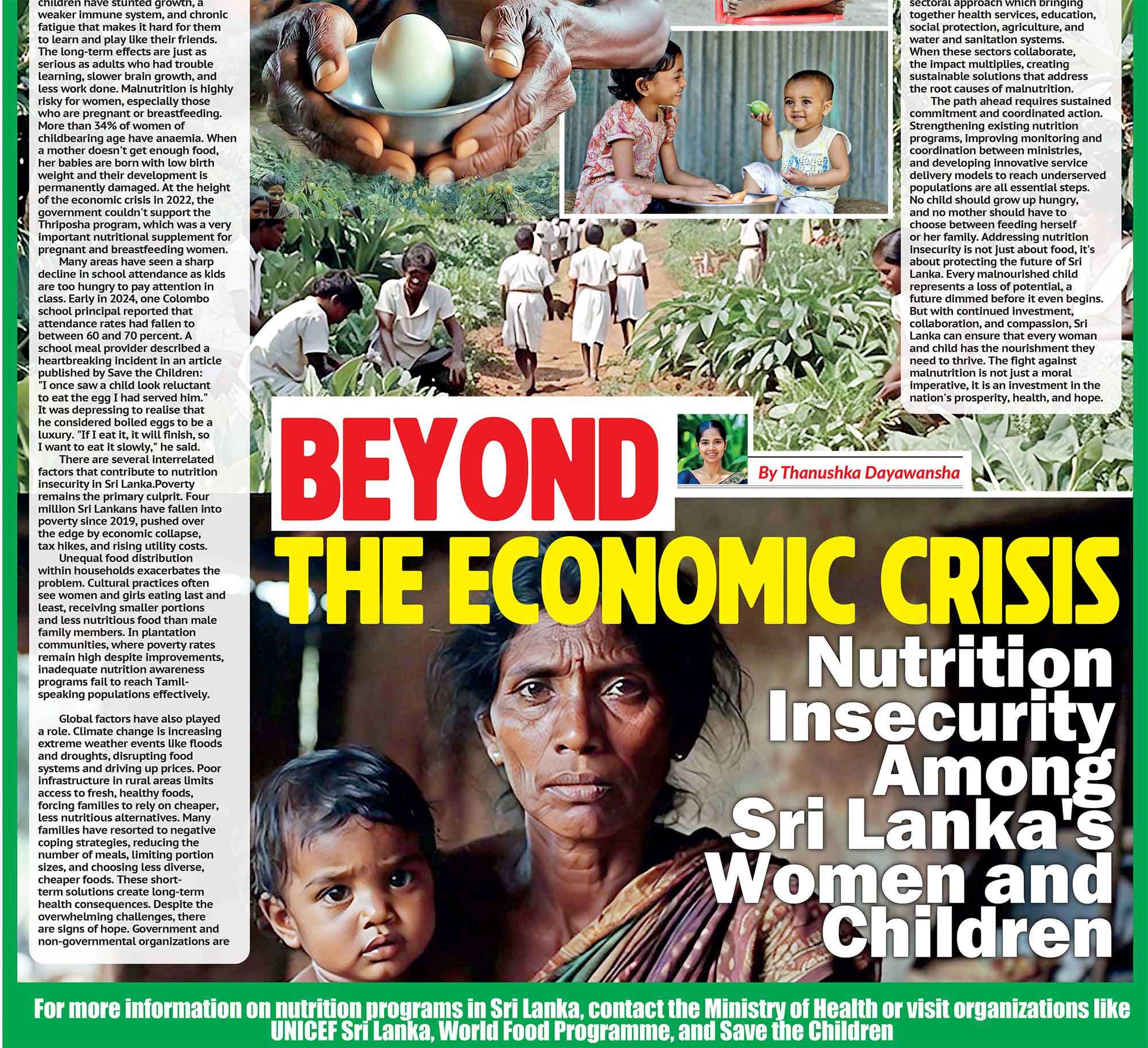

Across Sri Lanka, many women and children are quietly facing hunger and malnutrition. Rising food prices, poor diet, and lack of access to nutritious meals are leaving vulnerable families at risk, often without anyone noticing. As the nation emerges from its worst economic crisis in decades, the scars run deeper than empty wallets; they run through empty stomachs and malnourished bodies.

Across Sri Lanka, many women and children are quietly facing hunger and malnutrition. Rising food prices, poor diet, and lack of access to nutritious meals are leaving vulnerable families at risk, often without anyone noticing. As the nation emerges from its worst economic crisis in decades, the scars run deeper than empty wallets; they run through empty stomachs and malnourished bodies.

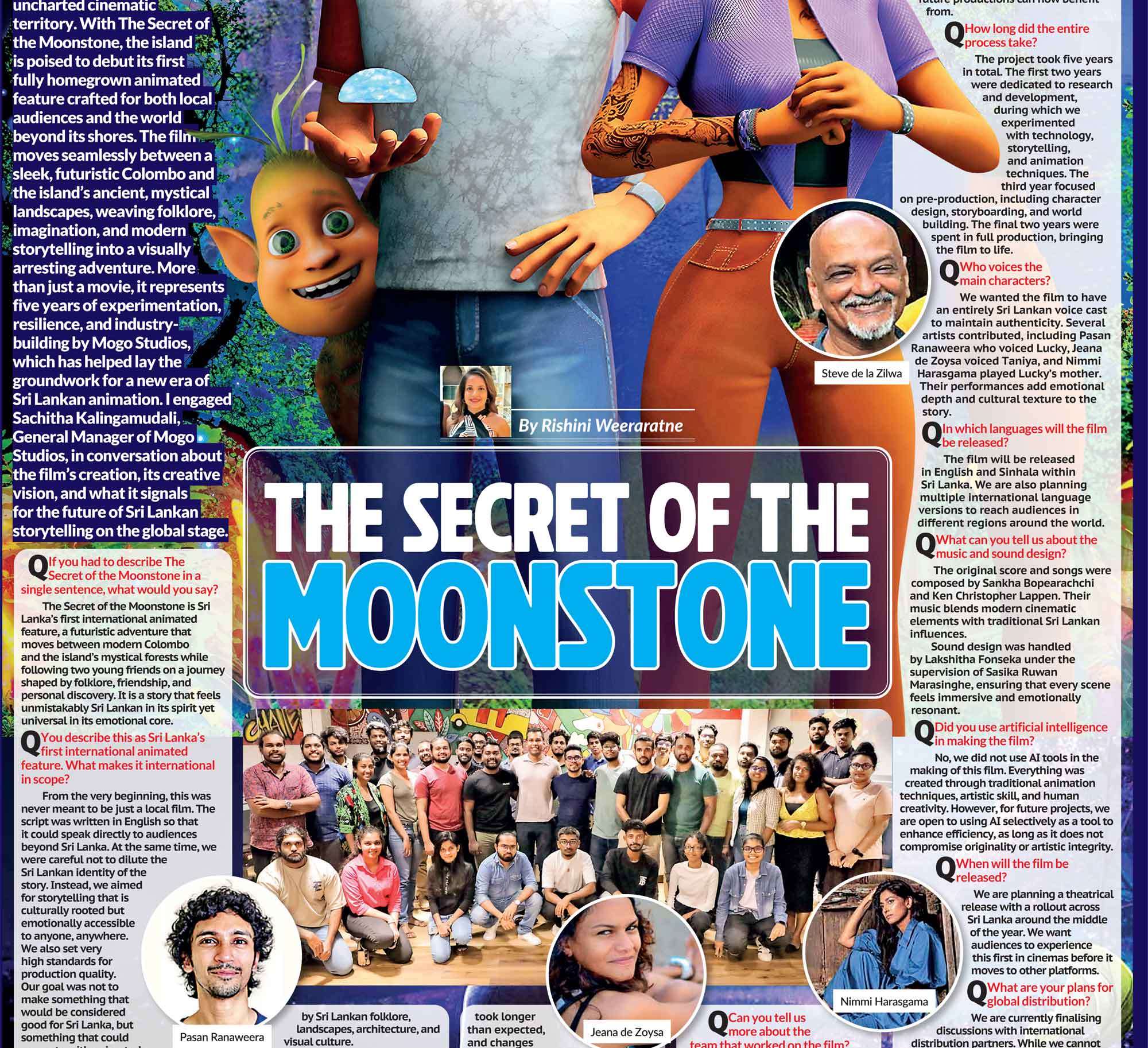

While Sri Lanka's economy shows signs of recovery, the reality for millions of households tells a different story. Following the 2022 economic crisis, food insecurity has gripped the nation with devastating consequences. Recent studies reveal that half of all households experienced moderate to severe food insecurity during the crisis, and the situation remains dire today. The numbers paint a grim picture. More than 10,000 children under the age of five suffer from severe acute malnutrition, according to the Ministry of Health's 2024 report. Wasting among school-going children has surged from 21 percent in 2023 to 26.8 percent in 2024. One in three children under five are malnourished, and an estimated 2.3 million children need urgent aid right now.

Rising food prices have become an insurmountable barrier for families that are having trouble making ends meet. In August 2024, the official poverty line was Rs. 16,152 per person per month, which is more than double the Rs. 6,966 that was recorded in 2019. Only 53 percent of the population could afford a healthy diet when prices went up. After the economic crisis, high food prices affected 98% of the population. Women and children have to deal with the most. Mothers often give up their own nutrition to feed their kids, putting their family's health ahead of their own. In rural areas and plantation estates, the situation is even worse: the rates of stunting and being underweight among children are much higher than in urban cities.

The negative consequences of not having enough food go far beyond just being hungry. Nutritionally deficient children have stunted growth, a weaker immune system, and chronic fatigue that makes it hard for them to learn and play like their friends. The long-term effects are just as serious as adults who had trouble learning, slower brain growth, and less work done. Malnutrition is highly risky for women, especially those who are pregnant or breastfeeding. More than 34% of women of childbearing age have anaemia. When a mother doesn't get enough food, her babies are born with low birth weight and their development is permanently damaged. At the height of the economic crisis in 2022, the government couldn't support the Thriposha program, which was a very important nutritional supplement for pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Many areas have seen a sharp decline in school attendance as kids are too hungry to pay attention in class. Early in 2024, one Colombo school principal reported that attendance rates had fallen to between 60 and 70 percent. A school meal provider described a heartbreaking incident in an article published by Save the Children: "I once saw a child look reluctant to eat the egg I had served him." It was depressing to realise that he considered boiled eggs to be a luxury. "If I eat it, it will finish, so I want to eat it slowly," he said.

There are several interrelated factors that contribute to nutrition insecurity in Sri Lanka.Poverty remains the primary culprit. Four million Sri Lankans have fallen into poverty since 2019, pushed over the edge by economic collapse, tax hikes, and rising utility costs.

Unequal food distribution within households exacerbates the problem. Cultural practices often see women and girls eating last and least, receiving smaller portions and less nutritious food than male family members. In plantation communities, where poverty rates remain high despite improvements, inadequate nutrition awareness programs fail to reach Tamil-speaking populations effectively.

Global factors have also played a role. Climate change is increasing extreme weather events like floods and droughts, disrupting food systems and driving up prices. Poor infrastructure in rural areas limits access to fresh, healthy foods, forcing families to rely on cheaper, less nutritious alternatives. Many families have resorted to negative coping strategies, reducing the number of meals, limiting portion sizes, and choosing less diverse, cheaper foods. These short-term solutions create long-term health consequences. Despite the overwhelming challenges, there are signs of hope. Government and non-governmental organizations are working to address nutrition insecurity through comprehensive programs.

The National School Meals Programme, in operation since 1931, has been expanded with support from organizations like Save the Children and the World Food Programme. As of 2025, over 100,000 primary grade schoolchildren across eight districts receive daily, protein-rich morning meals. In schools where the program operates, attendance has soared to 85-95 percent, and children report having more energy to learn and play.

The government invested Rs. 21 billion (approximately 70 million USD) in school meals in 2024, demonstrating a commitment to child nutrition. Private sector initiatives, including the John Keells Group's crowdfunding platform, have provided over 300,000 meals to children across Sri Lanka. Community-based approaches are making a difference as well. Mother support groups, home gardening initiatives, and climate-smart agriculture training are helping families build resilience. During the economic crisis, emergency cash transfers reached over 663,000 individuals, providing a lifeline for the most vulnerable.

Raising awareness about balanced diets and proper nutrition is crucial. Organizations are implementing behavior change communication strategies tailored to local communities, ensuring that information reaches even the most isolated populations. Promoting locally available, affordable nutritious foods can help families make better dietary choices within their limited budgets. The key to success lies in a multi-sectoral approach which bringing together health services, education, social protection, agriculture, and water and sanitation systems. When these sectors collaborate, the impact multiplies, creating sustainable solutions that address the root causes of malnutrition.

The path ahead requires sustained commitment and coordinated action. Strengthening existing nutrition programs, improving monitoring and coordination between ministries, and developing innovative service delivery models to reach underserved populations are all essential steps. No child should grow up hungry, and no mother should have to choose between feeding herself or her family. Addressing nutrition insecurity is not just about food, it's about protecting the future of Sri Lanka. Every malnourished child represents a loss of potential, a future dimmed before it even begins. But with continued investment, collaboration, and compassion, Sri Lanka can ensure that every woman and child has the nourishment they need to thrive. The fight against malnutrition is not just a moral imperative, it is an investment in the nation's prosperity, health, and hope.

For more information on nutrition programs in Sri Lanka, contact the Ministry of Health or visit organizations like UNICEF Sri Lanka, World Food Programme, and Save the Children.