Full Frontal By Chandri Peris

Life is similar to a game of snakes and ladders. Just when you think that everything is going well, you trip, you fall, and your recovery seems bleak. My life has had its fair share of highs and lows, but the trials and tribulations of the year that has just passed have been one that I don’t wish upon anyone. Yet, it has been a journey during which I learnt the most valuable lessons.

It was Plato who said, “No one is more hated than he who speaks the truth,” and I am a living embodiment of this saying. Much to my detriment, I have always “said it as it is” and upset more than a few apple carts, and I assume I will continue to do so till I am no more. I have a few friends who know me for who I am, and they confront me with the same brutal honesty, which I greatly appreciate. The world we live in is full of people who avoid confronting the truth, and they have developed the skill of papering over the cracks and presenting themselves to the world as being “holier than thou.” Yet, their efforts to present a wholesome image to the world require multiple appointments with psychoanalysts and large doses of anti-depressants. If all else fails, they resort to using opiates or drown their fears in pools of alcohol. Some spend their time virtue-signalling on social media as a process of denial. All of this is done to cover up the fracturing within their own souls. When Macbeth utters the line, “False face must hide what false heart doth know,” it heralds the beginning of a process of deception that leads to his complete meltdown. This is symptomatic of many people I know.

My own fall started without any outward signs at all. After having been consistently bullied by a female manager at work, I had unknowingly suffered two very minor heart attacks. I was also having huge mobility issues due to being denied knee replacement surgery by the NHS, despite having been on the waiting list for over eight years. I pursued the NHS complaints procedure and was successful in getting seen by a specialist who called for immediate surgery—only to be told by the surgical staff that they were not able to go ahead due to my heart condition. When the dots began to connect, my life began to fall apart. When I presented this evidence to the bully at work, requesting long-term leave for my operation and recovery, she and the HR team decided that having someone who was going to have one operation followed by another was not profitable to maintain. Adding salt to this festering wound were a few notable comments I had made at public meetings at work, which had marked me as a veritable target.

The first of these was my audacity to question and challenge the ease with which this same manager discussed “throwing acid on her face” when she wanted to stop an affair between a colleague and the CRM manager at work. The second instance was when I got up at a public meeting and questioned how employing only Muslims as apprentices at my workplace reflected London’s diversity. When a team member was given three months’ extended leave on the pretext that she was suffering from stress, I exposed the fact that she was babysitting her new grandchild and had managed to wangle this absence from work only because she was a friend of this same ghastly manager. I was also never supported by her on issues concerned with managing staff who did not pull their weight at work but did as little as possible. She fobbed me off by giving the official line which, in her words, “demonstrates inclusivity!” After eight months of fighting this pretentious rubbish, I decided I was too tired of putting up with this politically correct EDI hogwash any further—in July 2024 I left my workplace without any plans for the future.

Four months prior to this ordeal, I had undergone knee surgery. The day after my operation, I was brought back to my flat in an NHS ambulance and left to fend for myself. The operated knee was soaked in blood and covered in bandages. It was also about six times the size of the other! Making a cup of tea whilst balancing on crutches and drowning in a haze of painkillers proved to be an ordeal in itself. During this exhausting period of recovery, I was managing my work, as I had not been granted long-term sick leave. To make matters worse, not one “friend” came to help or even called to inquire how I was. It began to dawn on me that some would prefer to take long-haul flights to give koththamalli to a sneezing millionaire rather than travel a few stops on the tube to check on me. A handful of concerned parishioners from the church I attend began to offer their assistance in any way they could. What would I have done had it not been for the kindness of strangers? I often wonder.

To compound this situation, I made a rash decision to take a trip to France in search of some peace and support. All I encountered there was a diatribe of hatred aimed at my family and others who had a similar faith to mine. This was also aggravated by a stream of endless and noxious political discussions from a group of arrogant and self-serving individuals who were adept at turning to social media to support their dim-witted arguments whilst saturating in anti-depressants themselves. “Hate” filled the air to a point where I decided that being silent was my best defence. I withdrew into my shell, realising that this is part and parcel of what is taught and practised in France, they call it “Laïcité.” With friends like these, who needs enemies?

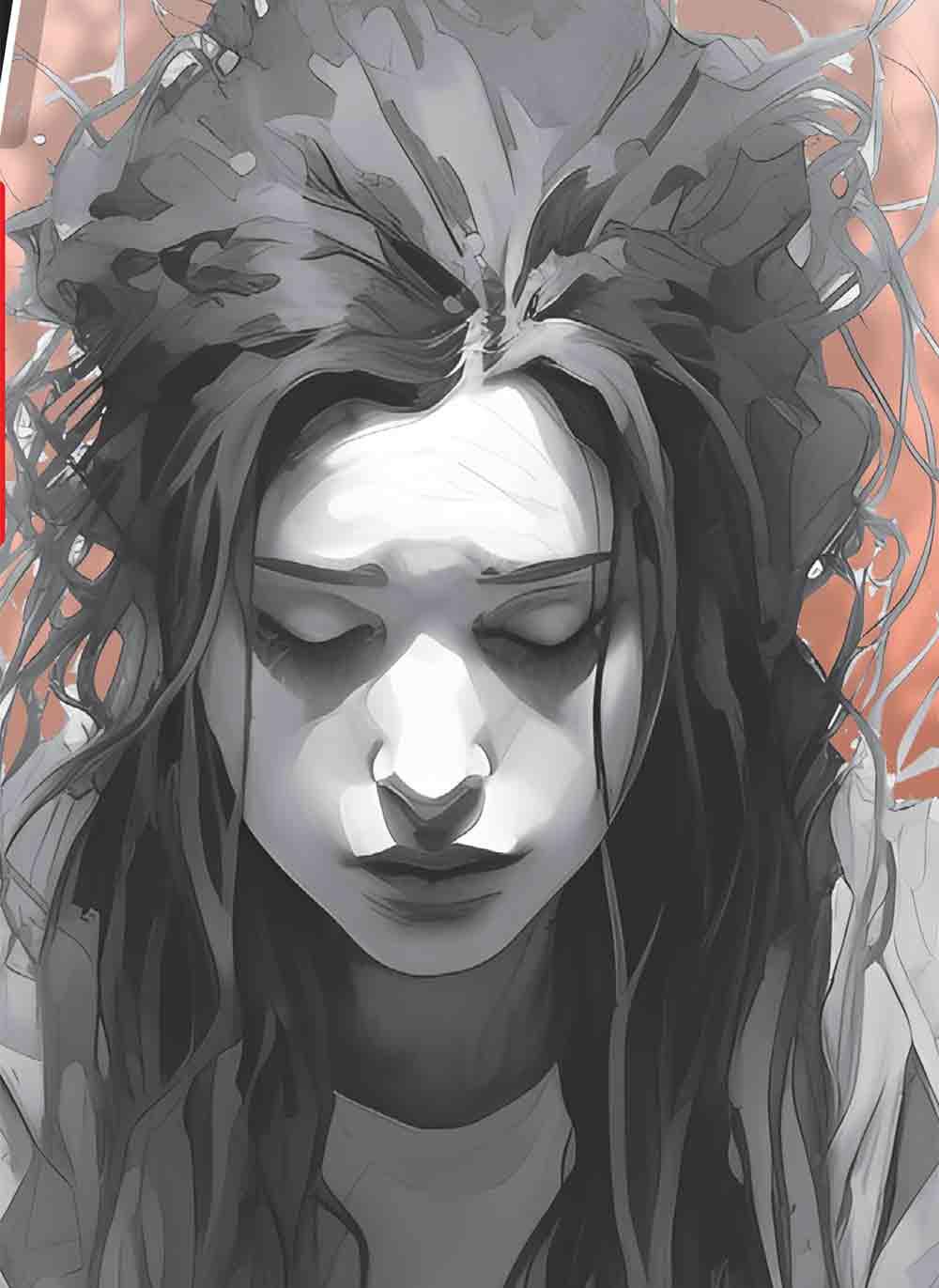

By October, the clouds of depression had truly started to gather. I found it difficult to get up from bed. I curled up in a foetal position, covered myself with a duvet, and did not want to face the light of day. It seemed like thousands of black birds were swarming in my head, making my world go dark. Yet, every single day I forced myself to look for jobs and continued to apply for various positions, only to be told that I am over-qualified. Age discrimination is rife in the UK’s job market. The very fact that I was being interviewed by some who were young and utterly inexperienced did not help. Even though I reached the final group of successful candidates for several positions on many occasions, my age and experience worked against me. This was after being shortlisted from over a thousand applicants for each of these jobs! The hopelessness felt bottomless. Twenty-two interviews later, I decided enough is enough! After three months of being unemployed, a nurse informed my GP that I was at breaking point. Her observation triggered alarms all over my borough, and doctors and therapists from unknown quarters started calling me to find out if I was feeling suicidal. This process, which is referred to as “social prescribing,” led to me being invited to attend talking therapies, speak to mental health counsellors, and also forced me to check in with a social worker on a frequent basis, just so that they could tick a box and say that I am still alive. It took all of this for me to realise that I had been diagnosed with depression.

My initial worry was about paying my bills and existing in this cold and unpleasant land. I spoke to a few organisations about my recourse to public funds but felt too ashamed to accept any. It was at this point that my only nephew, my dearest cousin from Sydney, and that wild and beautiful man who runs “Kess” called me, offering help. My pride has, and will always, prevent me from requesting financial help from anyone, but at this point in my life, it was their thoughts and kindness that held me up. When it came to dealing with my mental health, four good Samaritans went out of their way to talk me out of it. Two of them are sisters who attended my dancing classes. Their father was one of Sri Lanka’s most prominent swimming coaches. The younger sister called me regularly from Australia, encouraging me to throw away my medication and to fight back. Another is a dance partner of mine who is a lecturer in economics at the Sorbonne. She was so distressed about my condition that she called me daily, giving me rigid instructions on how to manage my life so as to avoid melancholy. The other is a banker from New York who has now returned to Colombo to pursue a career in fashion. She stood by me like a rock. These four heroic women talked me out of the hell I was in.

On the spiritual side of things, three other women stepped forward, offering me solace. One is an actress who has returned to Sri Lanka after many years in Dubai. Another is the managing director of Accenxia, and the third is my friend and dance partner who, despite having lost her husband recently, reached out to advise. Their message was simple and straightforward: “Ask – Seek – Knock.”

I began this year by throwing out my medication after taking it for less than a week. By May, the official letters regarding the possibility of retirement started coming through my mailbox. In June I received an offer of a job completely out of the blue. The clouds started dispersing fast; the light at the end of the tunnel began to get brighter. It feels as if a spell has been broken and everything has come together again. I may have lost some friends during this time, but I have gained my own sense of eremitism. Knowing that there are a few who are ready to catch me should I fall is evidence enough to realise that “my cup runneth over.”