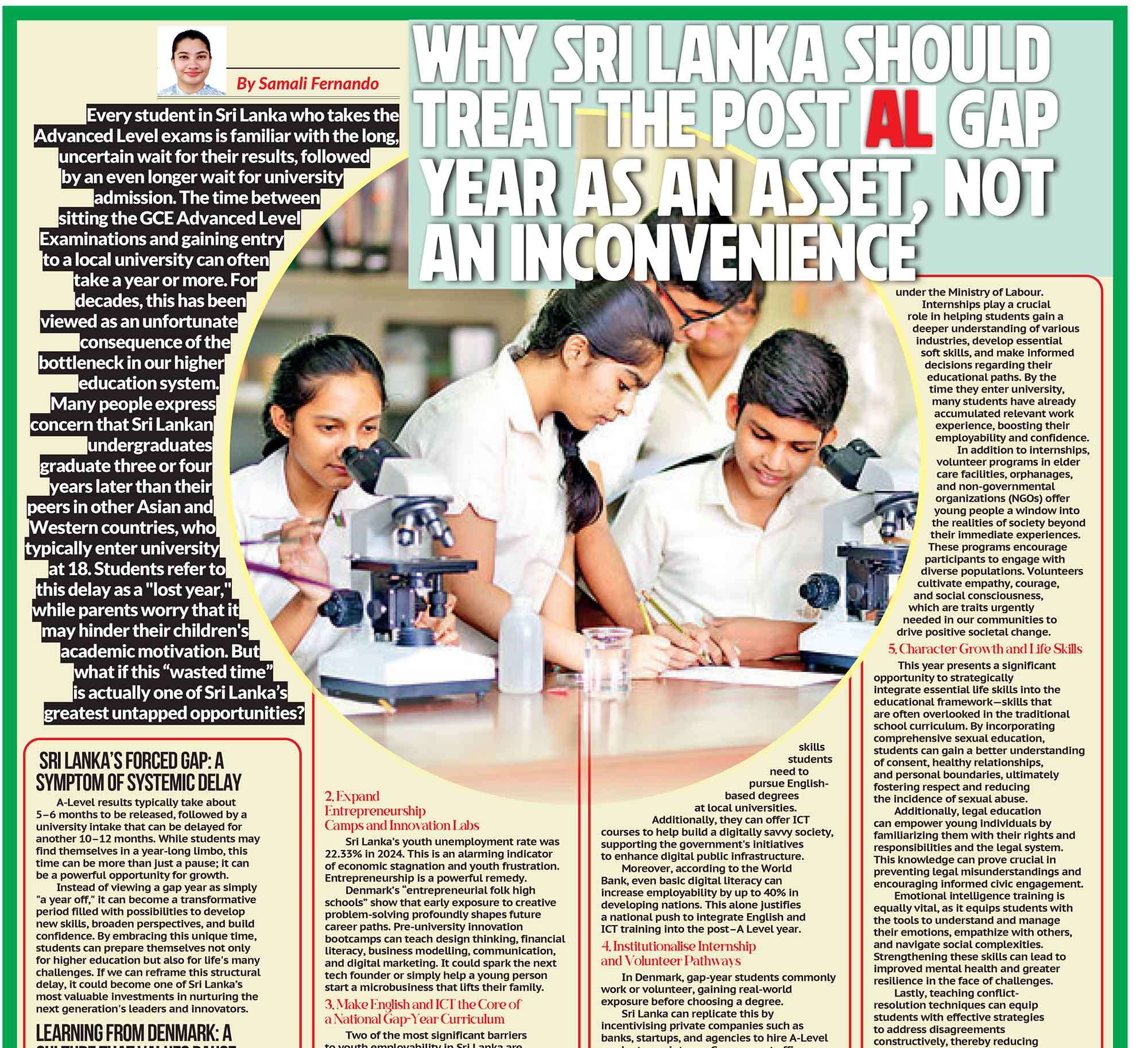

Why Sri Lanka Should Treat the Post AL Gap Year as an Asset, Not an Inconvenience By Samali Fernando Every student in Sri Lanka who takes the Advanced Level exams is familiar with the long, uncertain wait for their results, followed by an even longer wait for university admission. The time between sitting the GCE Advanced Level Examinations and gaining entry to a local university can often take a year or more. For decades,

Why Sri Lanka Should Treat the Post AL Gap Year as an Asset, Not an Inconvenience By Samali Fernando Every student in Sri Lanka who takes the Advanced Level exams is familiar with the long, uncertain wait for their results, followed by an even longer wait for university admission. The time between sitting the GCE Advanced Level Examinations and gaining entry to a local university can often take a year or more. For decades,

this has been viewed as an unfortunate consequence of the bottleneck in our higher education system. Many people express concern that Sri Lankan undergraduates graduate three or four years later than their peers in other Asian and Western countries, who typically enter university at 18. Students refer to this delay as a "lost year," while parents worry that it may hinder their children's academic motivation. But what if this “wasted time” is actually one of Sri Lanka’s greatest untapped opportunities?

Sri Lanka’s Forced Gap: A Symptom of Systemic Delay

A-Level results typically take about 5–6 months to be released, followed by a university intake that can be delayed for another 10–12 months. While students may find themselves in a year-long limbo, this time can be more than just a pause; it can be a powerful opportunity for growth. Instead of viewing a gap year as simply "a year off," it can become a transformative period filled with possibilities to develop new skills, broaden perspectives, and build confidence. By embracing this unique time, students can prepare themselves not only for higher education but also for life's many challenges. If we can reframe this structural delay, it could become one of Sri Lanka’s most valuable investments in nurturing the next generation's leaders and innovators

Learning from Denmark: A Culture That Values Pause

According to the OECD, 55% of Danish new entrants to Danish bachelor’s programmes take at least one gap year between finishing school and starting university. Far from harming academic progress, research shows that gap-year students often enter with higher motivation, emotional readiness, and a clearer sense of direction. The key difference? In Denmark, the gap year is intentional. It is not a failure of the system. It is culturally accepted, institutionally supported, and framed as productive time.

Reframing the Narrative: From Waiting to Building

Denmark teaches us that the time between school and university can be transformative when structured with purpose. Sri Lanka already has the ingredients for this transformation; we simply haven’t connected them. Here’s how we can turn this forced pause into a strategic investment in Sri Lanka's youth.

1. Elevate Vocational Training

Sri Lanka has a strong vocational ecosystem, with institutions such as VTA, NAITA, DDTET, UNIVOTEC, and others. In 2023 alone, Sri Lanka had 1,410 active vocational training institutes with over 120,000 students enrolled. These institutions offer short courses in hospitality, mechanical and electrical trades, ICT and coding, graphic design, and mechatronics. If promoted among school-leavers, vocational certificates could become parallel qualifications that complement university degrees. University cohorts would then consist of students who bring hands-on skills, technical exposure, and diverse interests creating a fertile ground for innovation. The only barrier is society’s perception. A rebranding campaign supported by government, the private sector, and the media can reposition vocational training as a career accelerator, not a fallback.

2. Expand Entrepreneurship Camps and Innovation Labs

Sri Lanka’s youth unemployment rate was 22.33% in 2024. This is an alarming indicator of economic stagnation and youth frustration. Entrepreneurship is a powerful remedy. Denmark’s “entrepreneurial folk high schools” show that early exposure to creative problem-solving profoundly shapes future career paths. Pre-university innovation bootcamps can teach design thinking, financial literacy, business modelling, communication, and digital marketing. It could spark the next tech founder or simply help a young person start a microbusiness that lifts their family

3. Make English and ICT the Core of a National Gap-Year Curriculum

Two of the most significant barriers to youth employability in Sri Lanka are English proficiency and digital literacy. The gap year offers the Sri Lanka National Institute of Education an excellent opportunity to provide English courses that develop the skills students need to pursue English-based degrees at local universities. Additionally, they can offer ICT courses to help build a digitally savvy society, supporting the government's initiatives to enhance digital public infrastructure. Moreover, according to the World Bank, even basic digital literacy can increase employability by up to 40% in developing nations. This alone justifies a national push to integrate English and ICT training into the post–A Level year.

4. Institutionalise Internship and Volunteer Pathways

In Denmark, gap-year students commonly work or volunteer, gaining real-world exposure before choosing a degree. Sri Lanka can replicate this by incentivising private companies such as banks, startups, and agencies to hire A-Level graduates as interns. Government offices should provide internship opportunities for school leavers by creating a National School-Leaver Internship Directory under the Ministry of Labour. Internships play a crucial role in helping students gain a deeper understanding of various industries, develop essential soft skills, and make informed decisions regarding their educational paths. By the time they enter university, many students have already accumulated relevant work experience, boosting their employability and confidence. In addition to internships, volunteer programs in elder care facilities, orphanages, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) offer young people a window into the realities of society beyond their immediate experiences. These programs encourage participants to engage with diverse populations. Volunteers cultivate empathy, courage, and social consciousness, which are traits urgently needed in our communities to drive positive societal change.

5. Character Growth and Life Skills

This year presents a significant opportunity to strategically integrate essential life skills into the educational framework—skills that are often overlooked in the traditional school curriculum. By incorporating comprehensive sexual education, students can gain a better understanding of consent, healthy relationships, and personal boundaries, ultimately fostering respect and reducing the incidence of sexual abuse. Additionally, legal education can empower young individuals by familiarizing them with their rights and responsibilities and the legal system. This knowledge can prove crucial in preventing legal misunderstandings and encouraging informed civic engagement. Emotional intelligence training is equally vital, as it equips students with the tools to understand and manage their emotions, empathize with others, and navigate social complexities. Strengthening these skills can lead to improved mental health and greater resilience in the face of challenges. Lastly, teaching conflict-resolution techniques can equip students with effective strategies to address disagreements constructively, thereby reducing incidents of violence and bullying. By prioritizing early exposure to these critical areas, we can significantly reduce societal issues such as domestic violence, sexual abuse, and suicide.

6. Mental Health: Recovering from the A-Level Storm

The A-Level journey is intensely stressful. A structured gap year gives students a chance to breathe. The gap year is a rare moment to reflect on their identities beyond academic labels and rediscover hobbies, explore passions, and understand themselves. For the first time, they are not just “students.” They are young adults learning who they are and who they want to be.

The Golden Opportunity We Keep Overlooking

Sri Lankan youth have endured economic crises, exam delays, political turbulence, and persistent uncertainty. Yet this frustrating pause everyone complains about could become a national strength if we treat it as Denmark does: a launchpad, not an interruption. A structured gap-year framework blending vocational training, English and ICT development, innovation camps, internships, life-skills education, and mental-health support can produce a generation that is more skilled, more adaptable, and more emotionally intelligent. As Sri Lanka moves forward with long-awaited education reforms, the forced gap year must be recognised as a strategic window for national human-capital development. Instead of struggling to eliminate it, we should invest in transforming it. The year we once called “lost” could become the year that changes everything.