A Global City in the Jungle

A Global City in the Jungle

Forget the image of Anuradhapura as an isolated city of monks. In its prime, it was a hub in a global network, sending embassies to Roman emperors, exchanging gifts with Chinese dynasties, and entertaining envoys from India. The chronicles hint at a city that was not only sacred, but cosmopolitan: a node where relics, spices, and politics crossed oceans. To understand Anuradhapura is to see it not as a provincial capital, but as a player on the world stage.

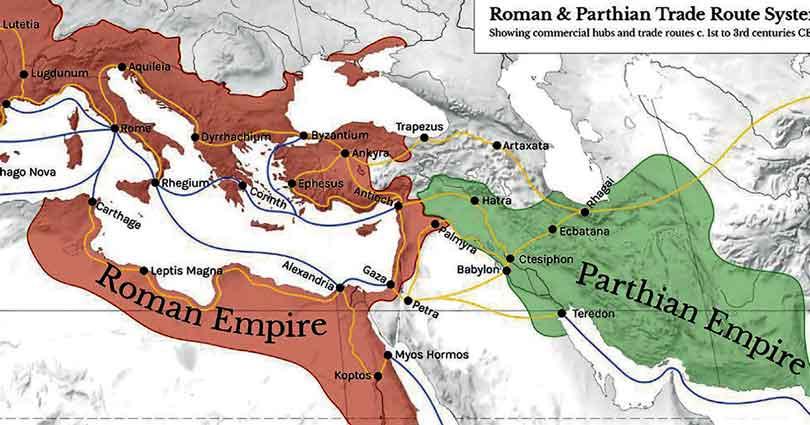

I. The Roman Connection: Coins and Embassies

Roman coins have turned up across Sri Lanka, from Mannar to Tissamaharama. The sheer volume is staggering, thousands of denarii and aurei stamped with emperors from Augustus to Constantine. To some, they were mere currency; to others, symbols of a transoceanic network binding the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. The Mahāvaṃsa records embassies sent westward, and classical writers noticed Sri Lanka in turn. The 1st-century Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions Taprobane as a trading emporium for elephants, gems, and spices. By the time of Claudius, embassies from Sri Lanka were appearing in Rome itself, described by Pliny as curiosities from a distant but powerful island. These were not trivial exchanges. Elephants, prized for war and ceremony, were a major export. Gems from Sri Lanka glittered in Roman circlets. Pepper, cinnamon, and pearls travelled westward, while wine, glass, and fine cloth travelled east. The Roman Empire knew Ceylon not as a mythic island, but as a partner in trade and diplomacy.

II. Gifts for the Dragon Throne: Sri Lanka and China

If Rome was the farthest west, China was the farthest east. Chinese chronicles, particularly the Hou Hanshu (Book of the Later Han) and the Xin Tangshu (New Tang History), record embassies from Shīlón (Sri Lanka). In 428 CE, an embassy arrived at the court of the Northern Wei. Later, in 742, another mission carried ivory, gems, and rare birds to the Tang dynasty. For the Chinese emperors, these visits were part of the “tribute system” - foreign kings acknowledging the Son of Heaven. For Sri Lanka, it was a chance to secure recognition as a legitimate Buddhist kingdom in the international order. Diplomatic gifts doubled as religious symbols: relics of the Buddha, manuscripts, and ritual objects passed across seas. The Chinese monk Faxian, who travelled through Anuradhapura around 410 CE, described the city’s monasteries as immense and orderly, housing tens of thousands of monks. He returned to China with texts and relics, ensuring that Anuradhapura’s image was preserved not only in stone but in ink. Through these exchanges, Sri Lanka became part of a trans-Asian Buddhist commonwealth.

III. India: The Near Abroad

No diplomatic story of Anuradhapura is complete without India. The island’s politics were deeply intertwined with its giant neighbour: marital alliances, shared religious traditions, and occasional invasions tied the two across the Palk Strait. Envoys from the Mauryan emperor Aśoka are said to have carried the Bodhi tree sapling to Anuradhapura in the 3rd century BCE, establishing both a sacred bond and a political alliance. Later, Pallava and Chola dynasties meddled in Sri Lankan politics, installing or supporting rival claimants to the throne. But diplomacy went both ways. Sri Lankan kings sent envoys to South Indian courts bearing gifts of ivory and pearls, and in return secured brides, warriors, or Buddhist texts. These constant exchanges show Anuradhapura as neither isolated nor subordinate, but as an agile player in a complex South Asian web.

IV. A Seaport Kingdom

How did a city hundreds of kilometres inland command such far-flung connections? The answer lies in Sri Lanka’s ports: Mahatittha (Mannar), Gokanna (Trincomalee), and Dambakolapatuna in the north. These harbours linked Anuradhapura’s bureaucrats and monks to the spice routes of the Indian Ocean. Greek ships stopped here on their way to the Ganges. Arab traders followed, bringing not just goods but ideas, astronomy, medicine, and new navigational skills. Each caravan that made the hot trek inland carried with it fragments of a wider world, depositing them in the capital’s monasteries and markets. Archaeological finds back this up: amphorae from the Mediterranean, beads from Persia, and seals in foreign scripts. Anuradhapura may have been landlocked, but its lifeblood pulsed through the salt wind of its seaports.

V. Relics as Diplomats

Beyond elephants and gems, Anuradhapura’s most powerful exports were sacred. The relic of the Buddha’s tooth, for example, was not just a religious treasure but a diplomatic instrument. Kings who held it claimed legitimacy; those who lost it risked rebellion. Foreign envoys often came seeking such relics, or at least tokens of Buddhist sanctity. A fragment of bone, a manuscript, even a monk could serve as a diplomatic envoy, sanctifying alliances in ways armies could not. In this sense, Anuradhapura’s diplomacy was not merely economic or political: it was theological. The kingdom exported holiness.

VI. The Cosmopolitan Capital

Picture Anuradhapura at its height: monks from China debating with Indian scholars in the shade of the Bodhi tree; Roman coins changing hands in the marketplace; Tamil merchants unloading cargo from the ports; ambassadors from Southeast Asia marvelling at the Ruwanwelisaya stupa. This was not a parochial city. It was a cosmopolis, a node in the first age of globalization, when the Indian Ocean bound civilizations together as tightly as any modern trade route.

Conclusion: A Kingdom on the World Stage

Anuradhapura was more than a city of kings and monks. It was an active participant in a global order, sending and receiving embassies, trading across continents, and exporting not just goods but ideas. To Rome, it was a source of wealth and wonder. To China, it was a Buddhist partner. To India, it was kin, rival, and ally. In remembering Anuradhapura, we should see not only stupas and ruins, but also ships, caravans, and envoys. Its legacy is not just carved in stone but carried in the memories of those who crossed seas to find it. The next time we think of Sri Lanka’s ancient capital, we should not imagine an island cut off from the world. We should picture a city alive with the noise of many tongues, where the jungle met the ocean, and where Sri Lanka spoke to Rome and China.