Fashion weeks are often slammed as hotbeds of excess, yet some of the most visible designers are using that very stage to show something different

This week the fashion world handed us a neat little exam: are we going to treat clothes like magic disposable things, or like the small, expensive decisions they actually are? From Paris runways to new industry clubs in Europe, the headlines are all nudging the same idea, less waste, more care. For those of us in Sri Lanka who love fabric, craft and story, these changes are both a nudge and an invitation.

Let’s warm up with the big picture. Europe, which generates mountains of discarded textile, has just seen a new player step onto the field: a coalition of industry groups trying to tackle textile waste properly. The group wants to build local textile-to-textile recycling hubs, scaling up ways to turn old garments back into new ones instead of letting them rot or be downcycled into cheap rags. That matters because right now only a tiny fraction of textile waste in Europe actually becomes new clothing again, and the coalition says that regional solutions (small, connected recycling centers) are one of the only realistic ways to change that. In short: clothes need a second life system, not just a landfill.

Next: denim. Jeans are a wardrobe staple everywhere, and a surprisingly heavy environmental offender. This week the Financial Times ran a friendly guide to the brands trying to make greener jeans, companies that use regenerative cotton, recycled fibers, water-saving dyeing processes and even repair services to keep jeans in circulation longer. The clever bit here is not just swapping materials but slowing the whole “buy, wear, throw” machine. If your favorite pair of jeans lasts longer (and can be mended), the planet breathes easier.

Now, if you’ve noticed your favorite brands suddenly sounding like thrift-store activists, you’re not imagining things. A wave of labels, from sneakers to dresses, are moving beyond eco-friendly fabric labels and into circular business models: take-back programmes, repair workshops, resale platforms and rental services. From big names to smaller labels, the message is: “We’ll help you keep what you buy in use.” These services make sustainable shopping practical: if a brand offers to repair your shoes or accepts them back for resale, you feel safer buying a piece in the first place, and the piece gets a new life afterward.

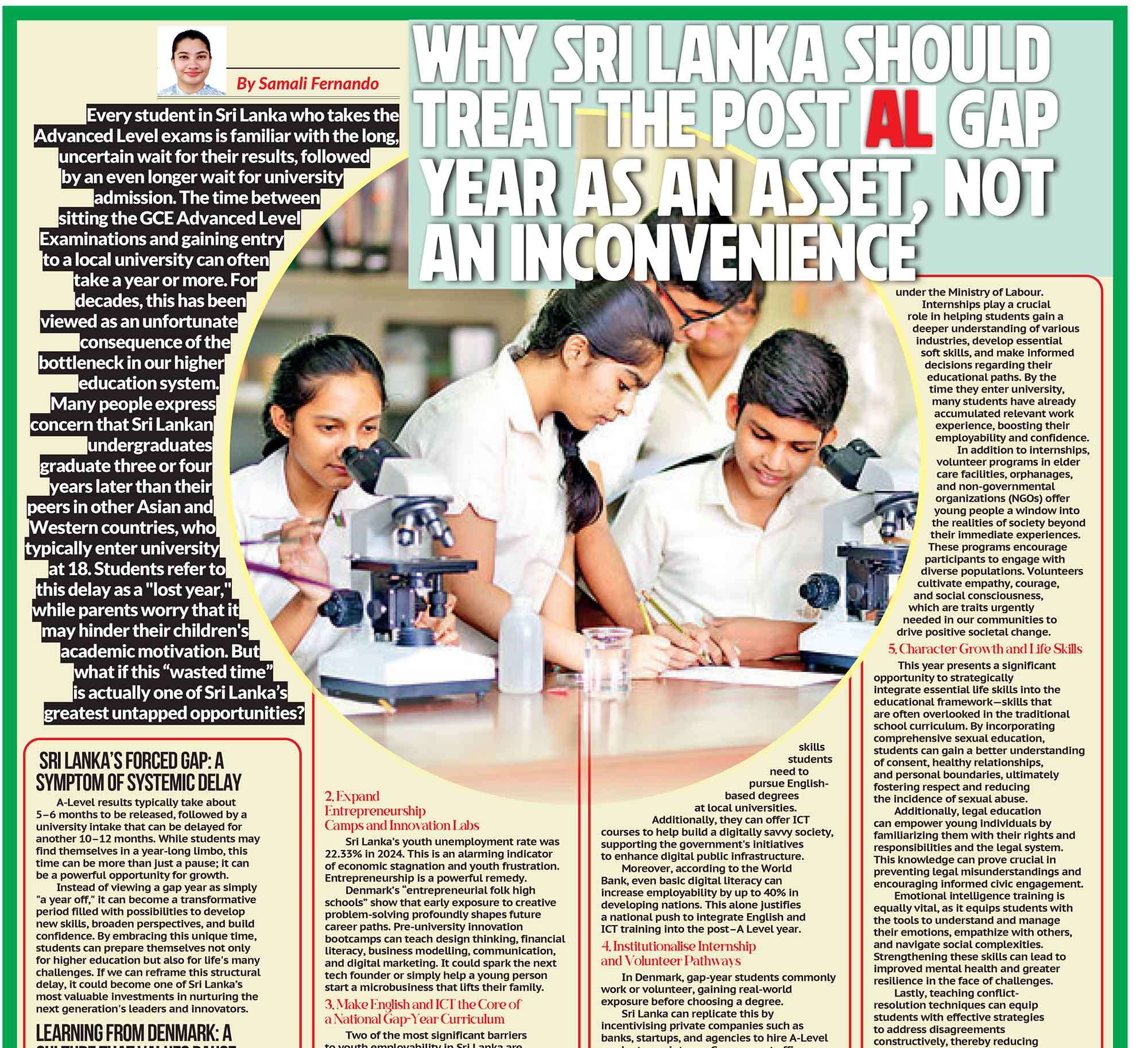

And the runways? Fashion weeks are often slammed as hotbeds of excess, yet some of the most visible designers are using that very stage to show something different. Stella McCartney, often called fashion’s eco-conscience, presented a collection that she described as almost entirely sustainable and completely cruelty-free, and the show was framed as a manifesto about humanity and the planet. That’s not just feel-good PR; when an influential designer pushes materials innovation (plant-based alternatives, upcycled denim, pollutant-absorbing textiles), it nudges suppliers and other brands to follow.

Meanwhile, fashion weeks are shifting geographically, too. Riyadh Fashion Week announced headline shows from designers like Vivienne Westwood and Stella McCartney, a sign that sustainability conversations are moving into new markets and that ideas about eco-fashion aren’t just European curiosities anymore. Global attention can help lift up local makers, if we make sure cultural exchange includes sustainable production, fair pay, and respect for craftsmanship.

So, what does all this mean for Sri Lanka, a country with a deep handloom history, a booming ready-made garment industry, and a community of artisans who make beautiful things by hand?

First, the good news: these global shifts create openings for us. Brands and buyers looking for recycled fibers, hand-finished pieces, and transparent supply lines are precisely the kind of partners Sri Lankan designers and weavers can work with. If international companies set up regional recycling hubs, Sri Lanka could explore partnerships for collecting and regenerating textile waste; an opportunity to create jobs while protecting craft. The key will be to ensure those jobs are dignified and the benefits reach the artisans, not only the middlemen.

Second, the practical at-home moves people can make are delightfully simple. Repair instead of replacing. Rent for a single-use occasion. Buy from makers who offer take-back or repair guarantees. These small choices are exactly what those “circular” brands are asking customers to do, and when many of us do the same, it changes demand.

Third, designers and small brands in Sri Lanka should treat these trends as design constraints rather than limits. Constraints breed creativity: designing for repair, using deadstock and leftover handloom, offering modular pieces that can be updated season after season, these are not sacrifices of style, they can be the starting point for identity. Your customer will love a story that goes beyond “pretty” to “purposeful.” Think of a sari-inspired jacket made from deadstock silk, it’s chic, it’s local, and it carries a story about value and craft.

There are a few caveats. Big sustainability claims need checking. When a brand says “green” it’s worth asking what that really means, is the fabric recycled, is the worker paid fairly, does the company take responsibility for its end-of-life waste? The new European rules (Extended Producer Responsibility) are meant to force those questions to the surface, and companies worldwide will be watching to see how these rules actually shape practice. Consumers and journalists, yes, that’s us, should keep asking the awkward questions.

And while it’s lovely when celebrities or big labels talk sustainability, local systems matter most. We need infrastructure for collection, repair, and recycling, not just good intentions. That’s where governments, industry bodies, and civil society can step in with policy and funding to support community-scale solutions.

What can readers do tomorrow? A short checklist:

- Mend a favourite garment, find a local tailor and make that pair of trousers last another year.

- Look for rental or resale options for special occasions.

- Ask your favourite store: do you repair? Do you accept returns for resale?

- If you sew or mend, teach a neighbour a basic stitch; skills spread faster than vinyl ads.

5.Support local artisans who use slow, high-quality processes; it keeps craft alive.

Fashion’s latest headlines feel less like a lecture and more like a friendly invitation. The industry is nudging toward repair tables and take-back bins, designers are experimenting with plant-based and upcycled materials, and even big shows are carrying an eco-message. For Sri Lanka, with our centuries old craft legacies and growing design talent, that’s an opportunity to step into conversations as makers, not just consumers. If global fashion wants stories and solutions, we have both; and perhaps a few beautiful, mended jeans to prove we care.