The Y chromosome has long been the symbol of maleness. It is the genetic spark that sets in motion the development of testes, the production of sperm, and the cascade of traits traditionally associated with men. Yet, despite its cultural and biological prominence, this chromosome is on a slow path to disappearance. Research shows that over hundreds of millions of years, the Y has shrunk dramatically. What was once a robust chromosome with hundreds of genes has been reduced to a fragile fragment containing just a few dozen functional genes. The implications of this decline raise questions that are both fascinating and unsettling: what would the world look like without the Y chromosome, and could humanity eventually evolve a new way to produce males?

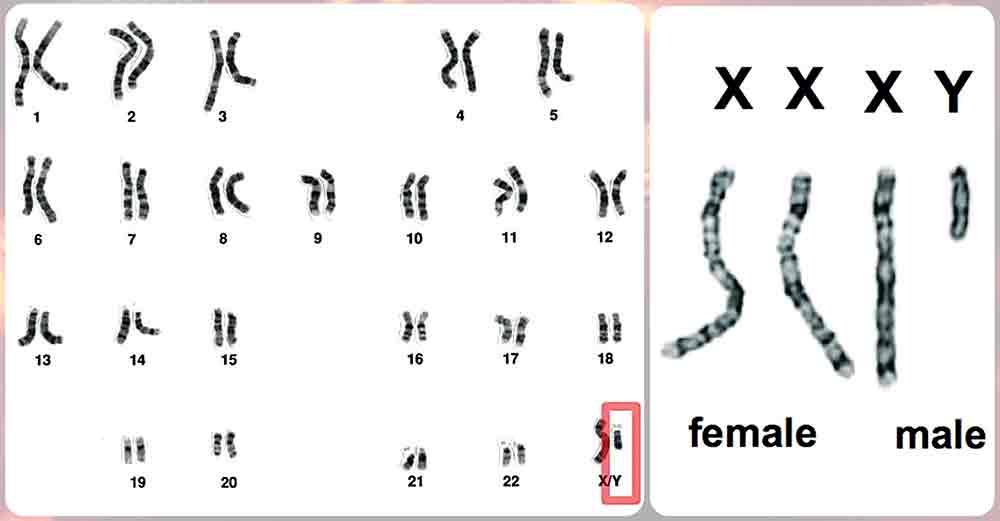

To understand the precarious state of the Y chromosome, it is essential to examine its history. The X and Y chromosomes were originally ordinary, identical chromosomes. Over time, one of these chromosomes acquired a gene called SRY, the master sex-determining gene. This gene triggers the development of testes in embryos, effectively establishing maleness. Once this specialization occurred, the X and Y chromosomes stopped recombining in males. Recombination is the process through which paired chromosomes exchange segments of DNA, correcting mutations and shuffling genetic material to maintain stability. Without a recombination partner, the Y chromosome became vulnerable. Mutations accumulated, and genes were lost. Today, only about 45 genes remain on the human Y chromosome compared to the hundreds retained on the X.

Jenny Graves, an Australian geneticist who has studied sex chromosomes for decades, explains that the Y is “essentially a relic of its former self.” Originally, the Y contained over nine hundred genes, many of which have been lost over 166 million years of evolution. Most of the sequences that remain now are repetitive and appear to serve little function. The few essential genes, including SRY, regulate sex determination and sperm production. Some researchers have argued that the rest of the Y’s DNA is genetic baggage, remnants of an ancient evolutionary experiment.

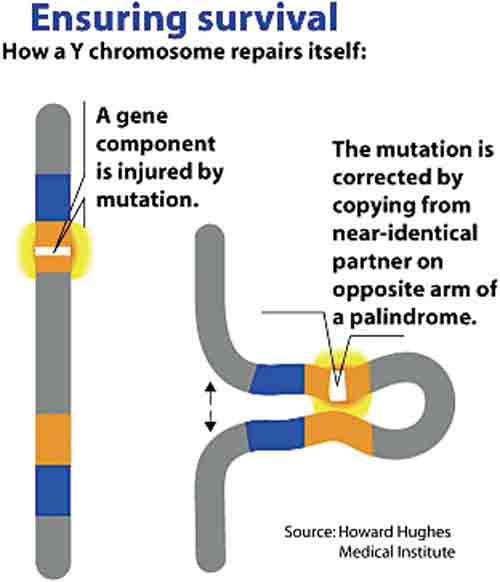

The Y chromosome’s vulnerability is compounded by the biology of reproduction. It is transmitted solely from father to son, and this male-limited inheritance means it cannot use recombination to repair damage. Sperm cells undergo countless divisions during development, creating more opportunities for mutation. In Graves’s words, “The testicle is a dangerous place to be. Each cell division is a chance for error. The Y has no partner to swap genes with. It is alone, exposed to every risk, and unable to repair itself effectively.” This combination of high mutation rates and isolation is why the Y has eroded so dramatically over time.

Despite these vulnerabilities, the complete disappearance of the Y chromosome is not imminent. Evolutionary calculations suggest that if the current rate of deterioration continues, the Y might vanish in six to seven million years. In the context of evolutionary time, this is rapid. Yet for humanity, which has existed for only 200,000 years in its modern form, this scenario remains a distant theoretical possibility. Even so, the idea that males could one day vanish has captured the imagination of scientists and the public alike, leading to sensational headlines about the “end of men.”

The story of the Y chromosome is not unique to humans. Other mammals and even some fish and amphibians have experienced similar chromosomal fates. In certain rodents, the Y has disappeared entirely. Three species of mole voles now carry only X chromosomes. These species have evolved alternative mechanisms for sex determination, relocating the essential genes once carried by the Y to other chromosomes. Spiny rats have undergone a similar transformation, replacing the Y with a novel chromosome that assumes its role in sex determination. These cases illustrate that the loss of the Y does not necessarily lead to extinction, but rather can be a prelude to evolutionary innovation.

The possibility of Y chromosome loss raises an intriguing question for humans: could our species evolve a new master sex gene? Graves argues that this is theoretically possible. In rodents, new sex-determining genes have emerged and successfully established themselves, effectively replacing the Y’s function. If a similar mutation were to occur in humans, it could create a new pathway for producing males without the traditional Y chromosome. Such a transformation would unfold over millions of years and could result in the emergence of entirely new mechanisms for determining sex.

Jenny Graves

Some researchers, however, take a more optimistic view of the Y chromosome’s resilience. Jenn Hughes, an evolutionary biologist at MIT, points out that the core genes of the human Y have been highly conserved for at least the past 25 million years. These genes play essential roles beyond sex determination, influencing functions throughout the body. The evolutionary pressure to maintain these genes is strong, and Hughes argues that this stability suggests the Y chromosome may be much more robust than previously thought. In her view, the Y has reached an equilibrium, a state in which further gene loss is minimal, ensuring the survival of males in the human species.

The debate between Graves and Hughes underscores a broader tension in evolutionary biology. It is difficult to predict the trajectory of a chromosome based on current observations alone. Genetic snapshots can appear stable for millions of years, yet underlying processes may continue to drive slow, incremental change. Graves remains cautious, noting that the Y’s apparent stability may be misleading. “Just because gene loss has slowed does not mean it has stopped,” she says. “Evolution proceeds in fits and starts. The Y may still be eroding, even if the signs are subtle.”

The history of human evolution offers additional perspective on the Y chromosome’s fragility. Neanderthals, our closest extinct relatives, experienced a form of Y chromosome replacement. Genetic studies suggest that Neanderthal males possessed Y chromosomes that were ultimately supplanted by those of modern humans during interbreeding events tens of thousands of years ago. This replacement underscores the capacity of the genome to adapt and reconfigure even critical sex chromosomes over evolutionary timescales.

Jenn Hughes

The potential disappearance of the Y chromosome also has broader implications for human biology. The Y carries genes that influence not only reproduction but also other aspects of male health, including susceptibility to certain diseases. Researchers have observed that men are more likely than women to lose parts of the Y chromosome as they age, a phenomenon linked to increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Understanding the dynamics of the Y is therefore not merely a theoretical exercise; it informs our understanding of human health and longevity.

While the Y’s erosion is a slow process, it offers a rare window into the mechanics of evolution. It is a story of vulnerability and adaptation, of loss and potential renewal. The examples of rodents and other mammals demonstrate that the disappearance of a chromosome is not an evolutionary dead end but a prompt for innovation. New sex-determining genes can arise, take hold, and stabilize within populations, ensuring the continuity of males even in the absence of the original Y chromosome.

For now, men are not at immediate risk of vanishing. The Y chromosome persists, carrying with it the essential instructions for male development and reproduction. Yet the possibility that it may one day be replaced by a new genetic mechanism invites a profound reflection on the nature of sex, gender, and evolution itself. Human biology is not fixed; it is an ongoing experiment conducted over millions of years. The Y chromosome’s story reminds us that even the most familiar aspects of our bodies are subject to change, subject to forces far larger than our own lifespans.

The vanishing Y is a tale of fragility, resilience, and the extraordinary creativity of evolution. It challenges our assumptions about permanence, offering a vision of a world in which the male sex may persist in entirely new forms. Whether the Y chromosome will ultimately survive or be replaced remains an open question, one that will continue to unfold over millions of years.

Reporting for this article was based on scientific research published in Current Biology and PLoS Genetics, alongside explanatory reporting from The Conversation, BBC Science Focus, and Earth.com.