A Kingdom that Wrote Itself

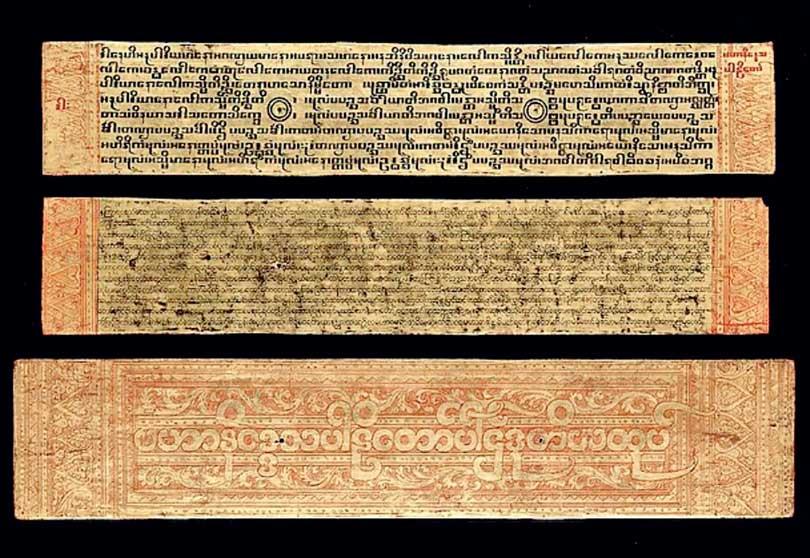

If Anuradhapura was a kingdom of stone, then its truest record is not its towering stupas but its carved inscriptions, hundreds of them, scattered across monastic caves, ruined vats, boundary stones, and ancient reservoirs. These short texts, often overlooked by popular memory, are the archival bedrock of the Sinhala polity. Long before the Mahāvamsa curated memory into myth, these epigraphs chronicled a living kingdom: naming donors, taxing lands, regulating water, and praising kings. The city, as it turns out, was not only imagined through rituals and relics; it was administered in stone.

The Rise of Script and the Birth of Governance

The earliest inscriptions in Anuradhapura appear in Brahmi script, dating to around the 3rd century BCE. They are brief, formulaic, and found primarily on cave shelters donated to monks; names of lay patrons, their lineage, and the phrase “dharma śasana śilā” (stone for the propagation of the teaching). But by the 1st century BCE, the language had evolved into Sinhala-Prakrit, a vernacular form of Indo-Aryan, and the content had diversified. We begin to see references to gam-bōjas (village assemblies), vetis (taxes), and pangu (shares of land). The state had begun to inscribe itself … visibly, and lastingly. As scholar H.P. Ray notes, these early inscriptions are the first signs of a polity "where the temple, the granary, and the archive were spatially entwined."

Who Writes, Who Rules: The Politics of Donative Inscriptions

Most inscriptions are not state decrees, but private donations, by merchants, landowners, soldiers, and, notably, women. A copper-plate grant from Vessagiriya records a woman named Bodhiyā who donates paddy fields to the monks of the Abhayagiri. This is not mere piety. It is a declaration of legal power, land ownership, and moral capital. These “donative inscriptions” are transactions in sovereignty. The donor gains religious merit, but also prestige; the monastery gains land, but also legal documentation. As epigrapher S. Paranavitana observed, this system functioned as an extrajudicial land registry, administered by stone and sanctified by belief.

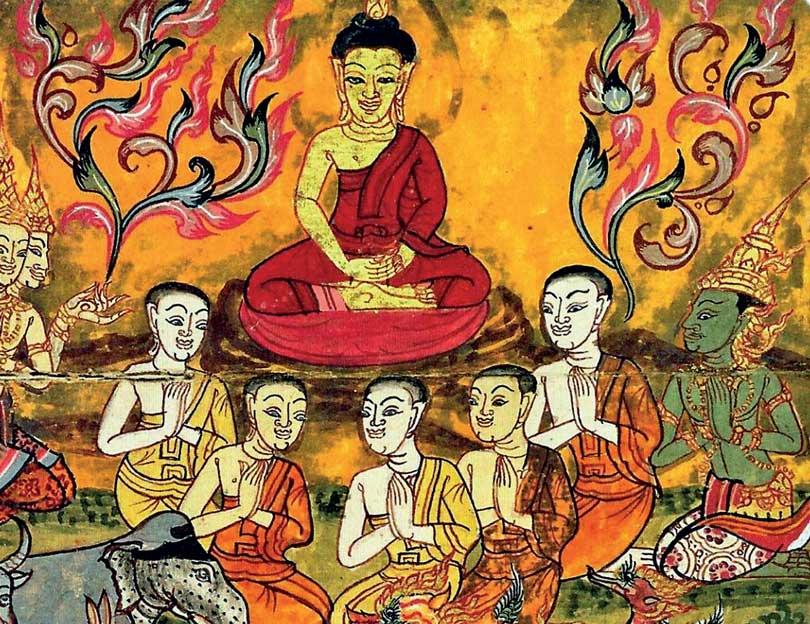

The Monastic State: Sangha as Landlords and Clerks

By the 2nd century CE, monastic institutions had become deeply embedded in governance. Monasteries held vast tracts of land; vāpikās (irrigated fields) and kataturahas (boundary tanks). Inscriptions from Mihintale and Abhayagiri refer to their own revenue collectors, storehouses, and even labour forces. Far from passive recipients of royal favour, the sangha was a parallel bureaucracy, issuing grants, arbitrating disputes, and sometimes resisting kings. When Mahāsena attempted to shift patronage from Mahāvihāra to Abhayagiri in the 3rd century, it was not just a religious act, rather an administrative coup.

As recent analysis by Nadeesha Gunawardana shows, these inscriptions reflect a “functional bureaucracy with Buddhist syntax” - monastic, yes, but deeply entangled in the affairs of the state.

Stratification in Script: Status, Caste, and Labor

Inscriptions also reveal a stratified society. Terms like velanda (merchant), dasa (servant), and kulika (artisan guild member) appear across cave epigraphy. The repetition of occupational identities, even in religious donations, hints at a quasi-caste system grounded not in Vedic vama, but in occupational pangu (shares). Some scholars, like Indrapala, argue that these repeated designations imply hereditary professions tied to monastic patronage. In other words, the sangha did not transcend social hierarchies, it helped formalise them.

The Bureaucracy Beneath the Stupas

Land grants were not just about agriculture, they were about control. Inscriptions frequently delineate boundaries using natural markers, trees, stones, streams, and contain warnings about violating grants. Some even invoke karmic retribution for trespass. This was law, recorded not in parchment but in geology. And because it was carved, it endured. From these fragments, we can reconstruct the silent governance of Anuradhapura: a kingdom that trusted stone more than scroll, and saw divine legitimacy in durable record.

Conclusion: Reading Between the Stones

Anuradhapura’s majesty lies not just in what it built, but in how it remembered. These inscriptions; humble, formulaic, often eroded, are the state’s self-portrait in its own time. They record more than merit: they record who owned land, who paid tax, who could speak, and who was seen. In the coming weeks, The Citadel Archives will turn to the temples and tombs, the queens and relics, and the foreign embassies of this extraordinary city. But we pause here, in front of the stones, to remember that every great kingdom is also a ledger. And Anuradhapura wrote its ledger in stone.