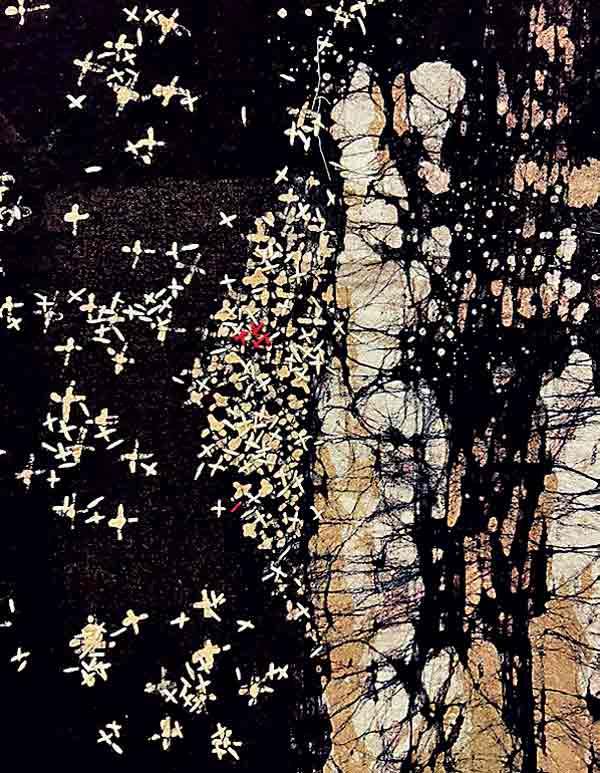

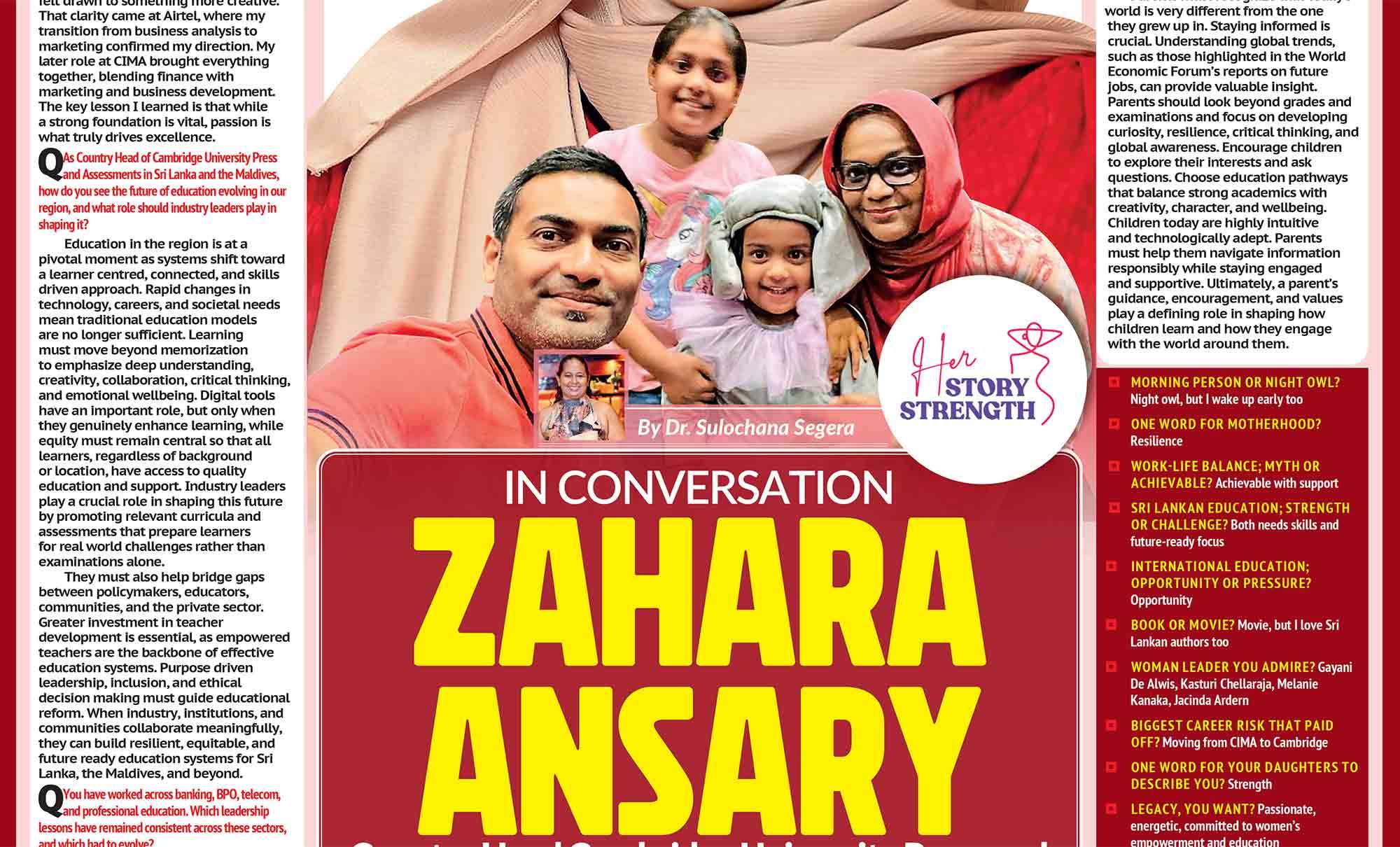

Sri Lankan artist Sonali Dharmawardena brings a distinct and deeply personal perspective to ‘The Series of Dialogue with Fabric,’ an exhibition that explores how batik can express emotion, memory and identity. Part of the EU–Sri Lanka Matchmaking Programme, the project highlights how traditional craft continues to evolve through contemporary artistic practice. Sonali’s work stands out for the freedom and honesty she brings to the medium, treating batik not as a fixed tradition but as a living form of expression. Through her practice, Art in Motion, she moves between fine art and fashion with ease, using fabric as a space to explore the pressures, vulnerabilities and quiet transformations that shape the inner self. Her piece ‘Shrouded Core,’ created for the exhibition, reflects this approach, capturing how everyday stresses leave marks on our emotional landscape. In this Q&A, Sonali speaks about her creative process, the role of freedom in her work and how batik continues to evolve as a powerful language of storytelling.

Q Your work often treats batik as a language of emotion and identity. How did the concept of “Dialogue with Fabric” first emerge in your creative process?

I have always identified as an artist. It feels natural for me to use the language of art to express emotion. My relationship with materials began in early childhood, when I was encouraged to create freely. I exhibited work with my art school friends from as young as eight or nine, using whatever I could find: fabric, thread, wool, paper, canvas, paint, even waste materials. That early experimentation naturally grew into a dialogue with fabric.

Q The resist-and-reveal nature of batik mirrors the ways we hide and expose parts of ourselves. How consciously do you work with this metaphor when layering wax and dye?

Hiding and exposing are part of human nature. The intensity and the areas in which we do so differ from person to person. Some of these actions are conscious, but many are unconscious and shaped by social, cultural, religious and economic environments. These layers inevitably surface in the batik process.

Q This programme bridges tradition and contemporary artistic practice. How do you see your relevance in redefining batik for a new generation?

I feel I can confidently say that I transformed the aesthetic through non-conformity, freedom of expression, open dialogue and authenticity. This alone redefines the medium. It also gives the new generation a canvas for expression, a space to create awareness and identity, and even a sense of therapeutic comfort.

Q You entered the world of batik without formal training, driven by a desire for artistic freedom. How has that sense of freedom shaped the evolution of your technique?

My technique evolved entirely through freedom.

Q Your piece Shrouded Core maps the psychological weight of daily pressures. What personal experiences or observations informed this work?

I grew up extremely sheltered and almost unrealistically protected from the existence of mental health issues and dysfunction. Confronting these realities later in life gave depth to the work.

Q The colours in Shrouded Core, beige, black and red, carry strong emotional symbolism. How do you approach colour selection when telling a story through fabric?

For me, colour selection is freedom. It is the act of pouring out whatever moves you. Colour and form become the way sincerity flows.

Q Much of your work explores how external forces mark the inner self. How do you decide which marks to leave intentionally, and which ones arise organically during the batik process?

When the process and the dialogue of the artist are honest, the marks that appear are unplanned. They flow naturally.

Q Your art often moves fluidly between wall panels and garments. How does the idea of art in motion influence the way you conceptualise a piece from the beginning?

I believe this is also reflected in what I have said earlier. In clothing, I do work with slight spatial restrictions, but I use the silhouette as the framework within which the dialogue continues.

Q This programme emphasises exchange between Sri Lankan heritage and international creative perspectives. How has that global dialogue influenced your understanding of batik as an evolving medium?

What is most important is evolution. When we work with authenticity and integrity, we naturally respond to our surroundings, and our work evolves. This becomes visible in the practice of any artist.

Q Batik is both a craft rooted in tradition and a tool for personal storytelling in your hands. What possibilities do you see for its future artistically, culturally or even therapeutically?

Batik is originally a craft. Most batik brands in Sri Lanka remain craft based, created by craftspeople. I too engage in the craft aspect, though more mildly, so that my community has opportunities for work. But the core of my practice is storytelling. It has been therapeutic for me, and it continues to be therapeutic for those who experience and use the work in context.