Enemies of the Crown

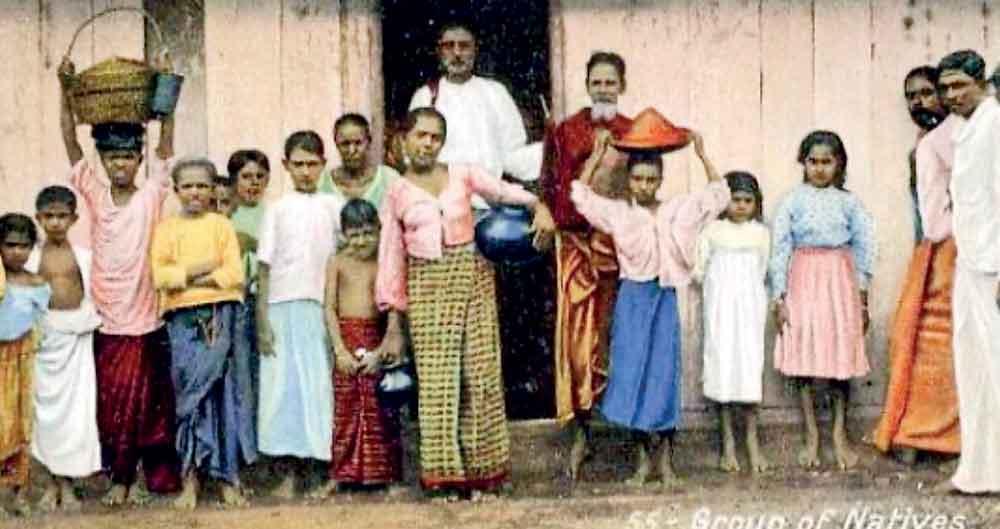

In the canon of Sri Lankan nationalism, resistance wears the cloth of kings and monks. But beyond the palace and the temple, in the forests and backroads, another kind of defiance festered, raw, romanticised, and often criminalised. These were the bandits, the renegade nobles, the villager turned insurgent, men who blurred the line between outlaw and freedom fighter, between treason and redemption. While colonial authorities inked them as marauders, the people remembered them otherwise: Robin Hoods in sarongs, Buddhist brigands, even patriots before patriotism had a flag.

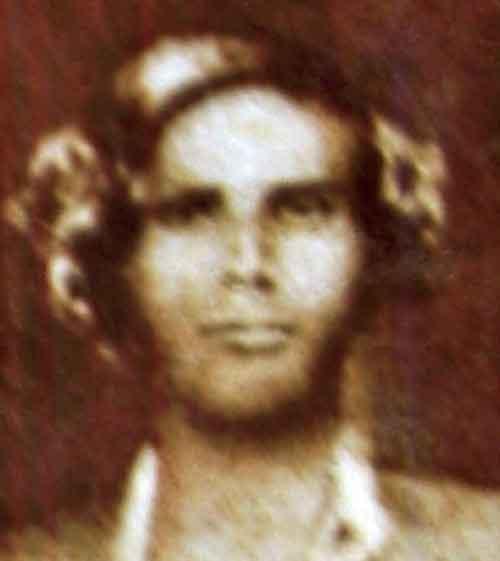

Sura Saradiel: Bandit or Folk Messiah?

At the heart of this archive of outlaws stands Sura Saradiel (1832–1864), the most famous anti-hero of colonial Ceylon. Born Deekirikevage Saradiel in the village of Utuwankande near Kegalle, he began his career as a tavern worker. But British injustice, particularly land seizures and tax raids; transformed him from worker to bandit, and then from bandit to legend. He raided British mail coaches, looted merchant convoys, and redistributed spoils to poor villagers, earning him comparisons to Robin Hood. He defied capture for over a decade, eluding colonial police with a combination of local knowledge, village networks, and near-mythical daring. Armed with a stolen revolver and clad in stolen khaki, he made the uniforms of his oppressors his own. Colonial records, such as the 1864 Ceylon Government Gazette, describe him as a “dangerous criminal who defied the law and inspired insurrection.” But song and verse, oral tradition paint him as a hero of the dispossessed. His final betrayal, by a local informant, and public hanging at the age of 32, only canonised him further. Folk ballads today still begin with “Saradiel wagey ekek apiṭa denne nedda?” - Will we never again have another Saradiel?

Keppetipola Disawe: From Crowned Agent to Crownless Rebel

If Saradiel was the bandit king, Monarawila Keppetipola Disawe was the general martyr of the hills. An aristocrat in the Kandyan court turned British-appointed provincial governor, Keppetipola initially served the very empire he would one day rebel against. When the 1818 Uva-Wellassa Rebellion erupted, arguably the most sustained anti-British insurrection of the 19th century, he was dispatched to suppress it. Instead, he joined the rebels, handing over British arms to the resistance and assuming military command. This act of betrayal earned him infamy among colonial officers, but immortality among the people. His execution, beheaded in Kandy, skull displayed in Colombo, was ritualised in British newsprint. But like William Wallace before him, his death gave rise to myth. His relics would later be reinterred with Buddhist honours in the 20th century. Unlike Saradiel, Keppetipola had a political vision: to restore the Kandyan kingdom, not just raid it. But both men shared a symbolic function. They reminded their contemporaries that the British crown, though armed and mapped, was not unchallenged.

If Saradiel was the bandit king, Monarawila Keppetipola Disawe was the general martyr of the hills. An aristocrat in the Kandyan court turned British-appointed provincial governor, Keppetipola initially served the very empire he would one day rebel against. When the 1818 Uva-Wellassa Rebellion erupted, arguably the most sustained anti-British insurrection of the 19th century, he was dispatched to suppress it. Instead, he joined the rebels, handing over British arms to the resistance and assuming military command. This act of betrayal earned him infamy among colonial officers, but immortality among the people. His execution, beheaded in Kandy, skull displayed in Colombo, was ritualised in British newsprint. But like William Wallace before him, his death gave rise to myth. His relics would later be reinterred with Buddhist honours in the 20th century. Unlike Saradiel, Keppetipola had a political vision: to restore the Kandyan kingdom, not just raid it. But both men shared a symbolic function. They reminded their contemporaries that the British crown, though armed and mapped, was not unchallenged.

Colonialism did not merely conquer by sword, but by redefining legality. The British restructured Ceylon's legal code, turning former noble warriors and provincial defenders into “rebels,” “bandits,” or “treasonous subjects.”

Rebels Without Archives

For every Saradiel or Keppetipola, there were dozens more nameless insurgents, village saboteurs, and guerrilla tacticians lost to imperial silence. The colonial regime did not see them as patriots. They were “mischief-makers,” “plunderers,” or “jungle vagrants”, recorded only in police logs and execution warrants. In southern Ceylon, 19th-century reports mention “gangs operating from the Ruhunu hinterland,” attacking plantations, torching tax offices, and sometimes allying with Buddhist monks. These fringe rebellions were often as much about economic justice [over tax grain levies, salt restrictions, and land displacements] as they were about nationalism. In eastern provinces, Tamil-speaking fisherfolk who resisted coastal regulations were branded pirates or smugglers but often acted as local protectors against exploitative levies. The boundary between the thief and the people’s champion was always thin.

Empire, Law, and the Manufacturing of Crime

Colonialism did not merely conquer by sword, but by redefining legality. The British restructured Ceylon’s legal code, turning former noble warriors and provincial defenders into “rebels,” “bandits,” or “treasonous subjects.” The Penal Code of 1883, based on the Indian template, was less about justice and more about containing sovereignty. Terms like “unlawful assembly,” “sedition,” and “obstruction of officer duties” were weapons of order, not neutral law. According to Nihal Perera (2004), colonial law was written “with the gun in one hand and the ordinance in the other.” Rebels were rarely tried with public defense. Courts often acted as rituals of imperial performativity, designed to show that justice wore boots, and spoke English.

The Antihero in Memory and Myth

What do we do with these figures, half-criminal, half-sacred? The 20th century nationalist movement sought to absorb them into its pantheon. Saradiel became a forerunner of Bandaranaike’s anti-imperial rhetoric. Keppetipola’s skull, once displayed as a warning, was recovered by the Department of Archaeology, and reinterred as a symbol of patriotic martyrdom. His face adorns currency notes; Saradiel’s name brands buses, shops, and a minor theme park. But their memory is complex. In their lifetimes, they did not claim the term “patriot.” They were men reacting to injustice in the language available to them, be it gunpowder, gallows, or guerrilla cunning. They offer us something richer than sainthood: they offer us moral ambiguity. They were not perfect. But they were real.

The Popular Afterlife of Resistance

In the age of cinema and algorithm, these figures have found new life. The 1980s film Saradiel recast the bandit as folk-saint. More recently, documentary-dramas, school plays, and are amongst a plethora of modern revisionist retellings have turned rebels into icons. But what these retellings often miss is the complicated nature of colonial resistance. It was not always orchestrated, nor ideologically pure. Sometimes it was simply rage against enclosure. A rice tax too many. A forest confiscated. A humiliation repeated. These rebels do not belong to the margins of history. They were its destabilisers, figures whose names survive not through royal decrees or colonial dispatches, but through the stubborn persistence of local memory and political myth.

What do we do with these figures, half-criminal, half-sacred? The 20th century nationalist movement sought to absorb them into its pantheon. Saradiel became a forerunner of Bandaranaike’s anti-imperial rhetoric

The Empire’s Shadow Archive

We do not hear these men in their own voices. What survives are records of accusation, court proceedings, colonial proclamations, and the fragmentary echoes of oral tradition. Their legacy lies not in authored texts, but in the institutional traces of those who tried to erase them. If we are to read them rightly, we must read against the grain. We must see the law not just as law, but as colonial theatre. We must hear not just the gunshot, but the reasons it was fired. The empire’s most wanted were not always the people’s most feared. Often, they were the people’s only hope.