A Kingdom Worth Returning To For a kingdom that endured over a millennium, Anuradhapura appears in our national memory with surprising simplicity. It is recalled through monumental stupas, irrigation marvels, and saintly kings; reduced, more often than not, to a constellation of pious images. But Anuradhapura was never merely a capital; it was the architectonic genesis of Sri Lanka’s statecraft, the ideological crucible from which the very notion of Sinhala kingship was forged. Beginning with this article, The Citadel Archives will dedicate the coming weeks to a sustained historical inquiry into the Anuradhapura Kingdom, not as myth or monument, but as an evolving political, religious, and ecological reality. We begin with its emergence, before the chronicles, before the temples, to trace the city before the story.

01)

Pandukabhaya and the Politics of Origin

In the Mahāvamsa, the great Pali chronicle composed around the 5th century CE — Anuradhapura’s founding is ascribed to King Pandukabhaya, a figure as legendary as he is formative. The text, with near-bureaucratic precision, attributes to him the construction of water tanks (vāpi), cemeteries, yaksa shrines, and demarcated quarters for ascetics, Brahmins, and herdsmen. He is said to have built Abhaya-vāpi, still extant today as Basawakkulama, laying the infrastructural and cosmological foundation of the city. But modern historians treat such accounts with caution. As K.M. de Silva and R.A.L.H. Gunawardana have shown, these chronicles are ideological texts, composed centuries after the events they purport to narrate. Their function was not to record history as we understand it, but to legitimise Theravāda kingship and portray the island as a chosen vessel for the Buddha’s teaching. Hence, the tales of Vijaya’s arrival and Pandukabhaya’s city-building are less empirical records than charter myths, designed to sanctify dynastic succession and urban order. To reach the historical Anuradhapura, one must dig deeper; literally and figuratively.

02)

Beneath the Text: The Archaeology of the Anuradhapura Citadel

Excavations at the Anuradhapura Citadel, particularly by Robin Coningham and his team (1990s–2000s), have unearthed a much older layer of occupation than the Mahāvamsa implies. Settlement at the site dates back to at least 900 BCE, well before the alleged arrival of Vijaya in 543 BCE. These earliest layers contain evidence of a megalithic cultural complex — cremation burials, black-and-red ware ceramics, iron tools, and subsistence farming. This community appears to have evolved in situ, rather than having been transplanted from India. Karthigesu Indrapala argues persuasively that Sinhala identity did not arise from a single migratory event, but from the interaction between local megalithic peoples, North Indian influences, and later Dravidian contacts. Anuradhapura’s emergence, then, was not the result of a sudden founding, but a slow coalescence of settlement, trade, ritual, and ecology.

03)

Water and World-Making: The Hydro-Politics of Kingship

The earliest infrastructure projects of Anuradhapura were not palaces or temples, but tanks. The Abhaya-vāpi, the Nuwara-vāpi, and the later Tissa-vāpi reflect an early understanding that kingship in the dry zone demanded control over monsoon cycles and water flow. Hydraulic construction was not merely utilitarian. John Holt, in The Religious World of Kandy (1996), emphasises the ritual and symbolic dimensions of water management. A king who controlled the rains, or appeared to, could present himself as a dharmic sovereign, one who sustained both the body of the state and the moral order. Thus, hydraulic engineering became both a technocratic project and a theological performance. The alignment of tanks, paddy fields, and monasteries formed a spatial theology in which Buddhist merit and royal efficacy were mutually reinforcing.

04)

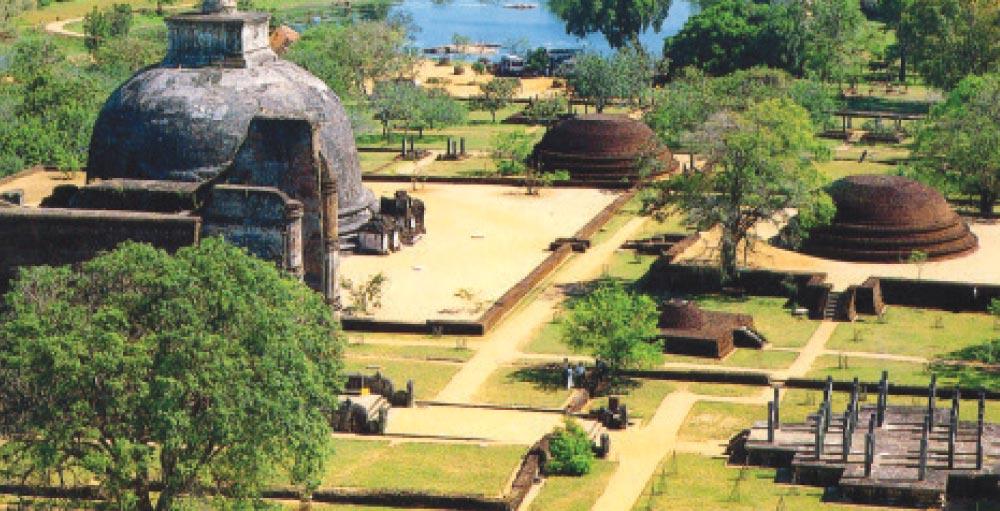

Ritual Geography and the Architecture of Sovereignty

By the 3rd century BCE, Anuradhapura had transformed into a sacralised urban centre, where political space and ritual space were indistinguishable. The Thuparama, built by Devanampiya Tissa after the introduction of Buddhism (c. 250 BCE), stands as the first stupa on the island. Later stupas — Ruwanwelisaya, Jetavana, and Abhayagiri — were not just religious sites, but monastic polities, with independent landholdings, administrative apparatuses, and doctrinal lineages. As the monastic community (sangha) grew, so did its entanglement with the state. By the time of Mahasena (3rd century CE), the city had become a ritual archipelago, where every corner reinforced the legitimacy of kingship. It is no accident that Buddhist relics, the bodily remains of the Buddha, became royal regalia. To rule Anuradhapura was to administer not just a kingdom, but a cosmic order.

05)

Merchants, Guilds, and the Cosmopolitan Court

Though the chronicles rarely admit it, Anuradhapura was a trading city. Roman coins, Persian ceramics, and Chinese glassware unearthed from the site tell of its place in Indian Ocean networks. Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions at nearby sites like Tissamaharama indicate early Dravidian influence, suggesting that the city was never culturally insular. Guilds (śreni), merchant caravans, and foreign monks were part of Anuradhapura’s daily life. The court, while ritualised, was also a space of diplomacy, commercial arbitration, and cross-cultural encounter. Even the Buddhist canon, preserved in Sri Lanka’s Alu-vihāra Cave, reflects centuries of interregional debate and textual circulation.

06)

The City’s Afterlife: Memory and Monumentality

Anuradhapura fell in the 11th century, its flame transferred to Polonnaruwa, yet it never vanished. Its stupas remained objects of veneration, its tanks were maintained or rebuilt, and its layout continued to shape the cities that followed. Even today, Anuradhapura functions less as an archaeological site than as a living monument, a place where schoolchildren chant Pali verses and pilgrims circle stupas under moonlight. But beneath this devotional surface lies a more difficult, more thrilling truth: The Anuradhapura Kingdom was not inevitable. It was constructed; from ecology, migration, religion, trade, and imagination.

07)

Conclusion: Toward a New History of Anuradhapura

In the weeks to come, we shall explore Anuradhapura in greater depth. From the role of queens and monks, to the cult of relics, to epigraphic landscapes, we will trace the evolving logic of Sri Lanka’s first kingdom. But we begin here, at the moment of origin, not to worship the past, but to interrogate its architecture. For beneath every stupa is a story, beneath every tank a politics, and beneath every chronicle an argument about what the island was, and who it was for. Let us begin again, with Anuradhapura — the city before the chronicle, and the memory behind the monument.