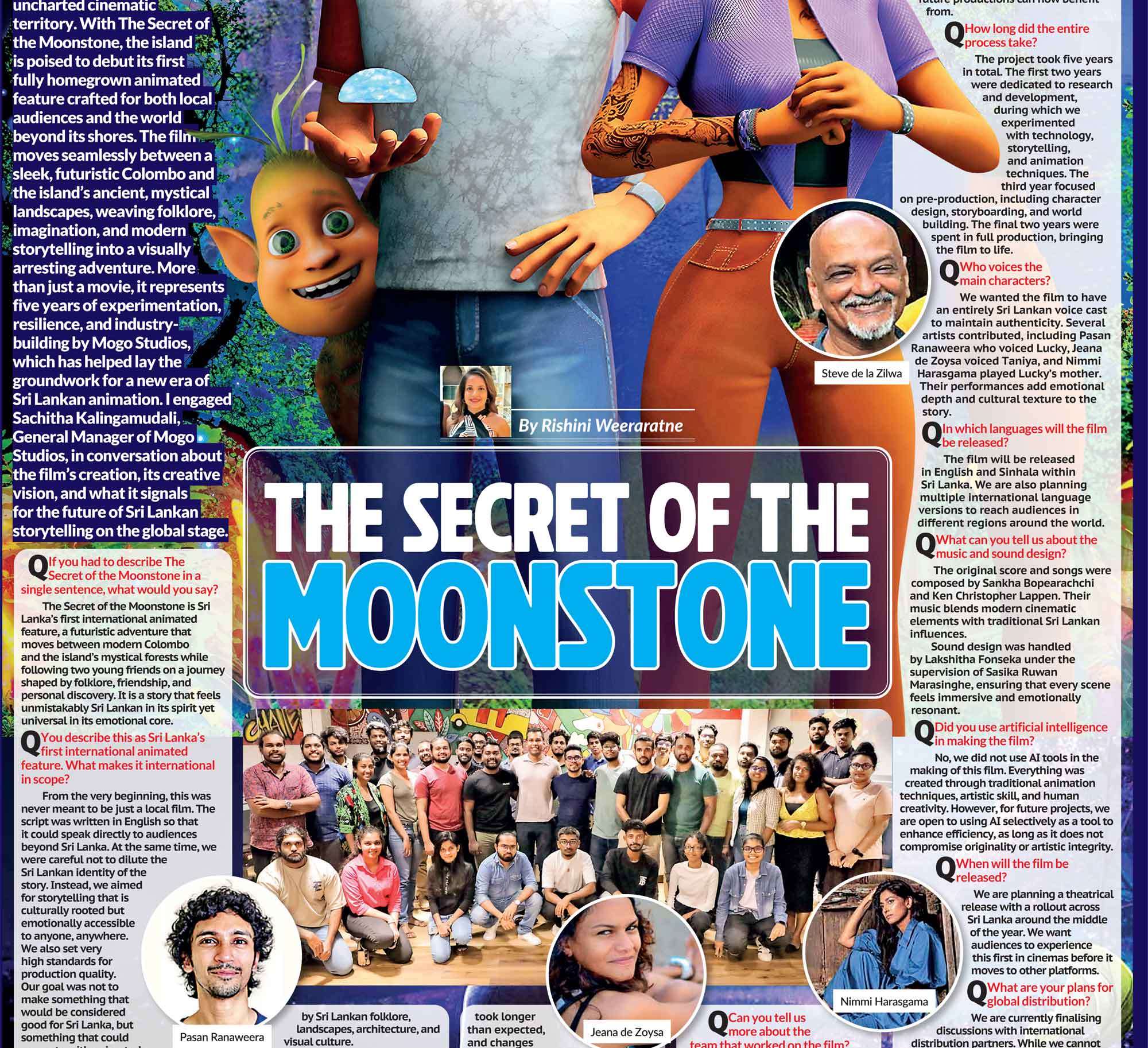

His Highness the Aga Khan IV (1936–2025)

Prince Amyn Aga Khan

Fairouz Nishanova

London feels inevitable,” said Fairouz Nishanova, Director of the Aga Khan Music Programme, which administers the Awards. She was born to Uzbek parents in Sri Lanka

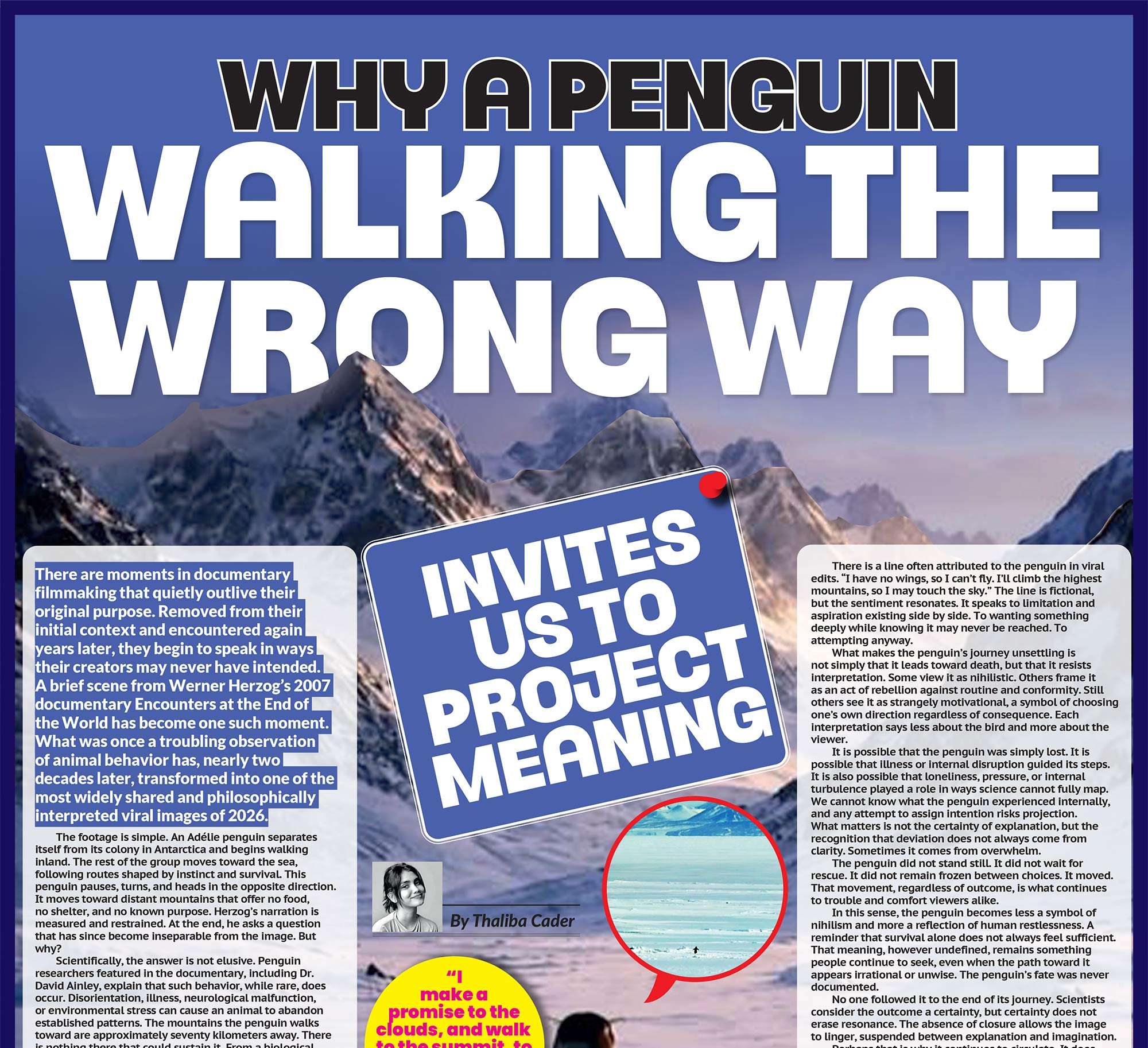

In November 2025, as the fog settles over London’s Southbank, a different kind of resonance will take over the air. The Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, and the Purcell Room will host an event that stretches far beyond performance: the Aga Khan Music Awards (AKMA), returning for its third edition and marking its first appearance in London.

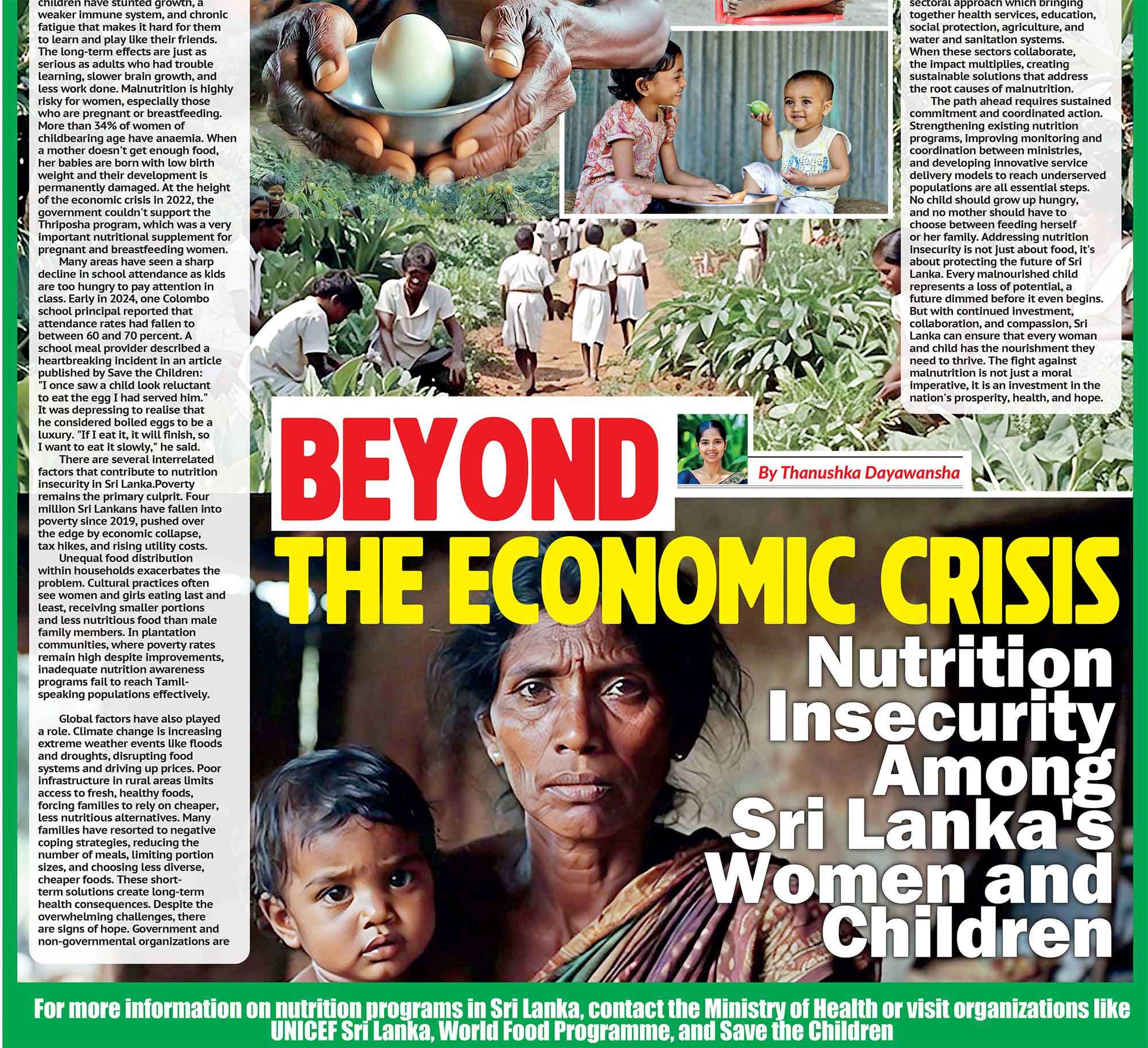

The Awards, founded by the late His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IV in 2018, were born from a simple but ambitious belief that music, when nurtured and understood, can become a language of dignity, pluralism, and peace. In a world where cultures increasingly exist behind digital screens and sharp divides, the Aga Khan Music Awards seek to do what music has always done best: connect.

Every three years, the Awards gather musicians, composers, educators, and preservationists from across the diaspora. They celebrate artists whose work breathes new life into centuries-old sounds. The Awards honour not only artistry but endurance, recognising those who have chosen to carry tradition into modernity without diluting its essence.

This year’s edition will run from the 20th to the 23rd of November in partnership with the EFG London Jazz Festival, an institution that, like the Awards, celebrates improvisation as a bridge between past and present. It is a fitting collaboration, for both see music as a form of dialogue, a conversation across geographies and beliefs.

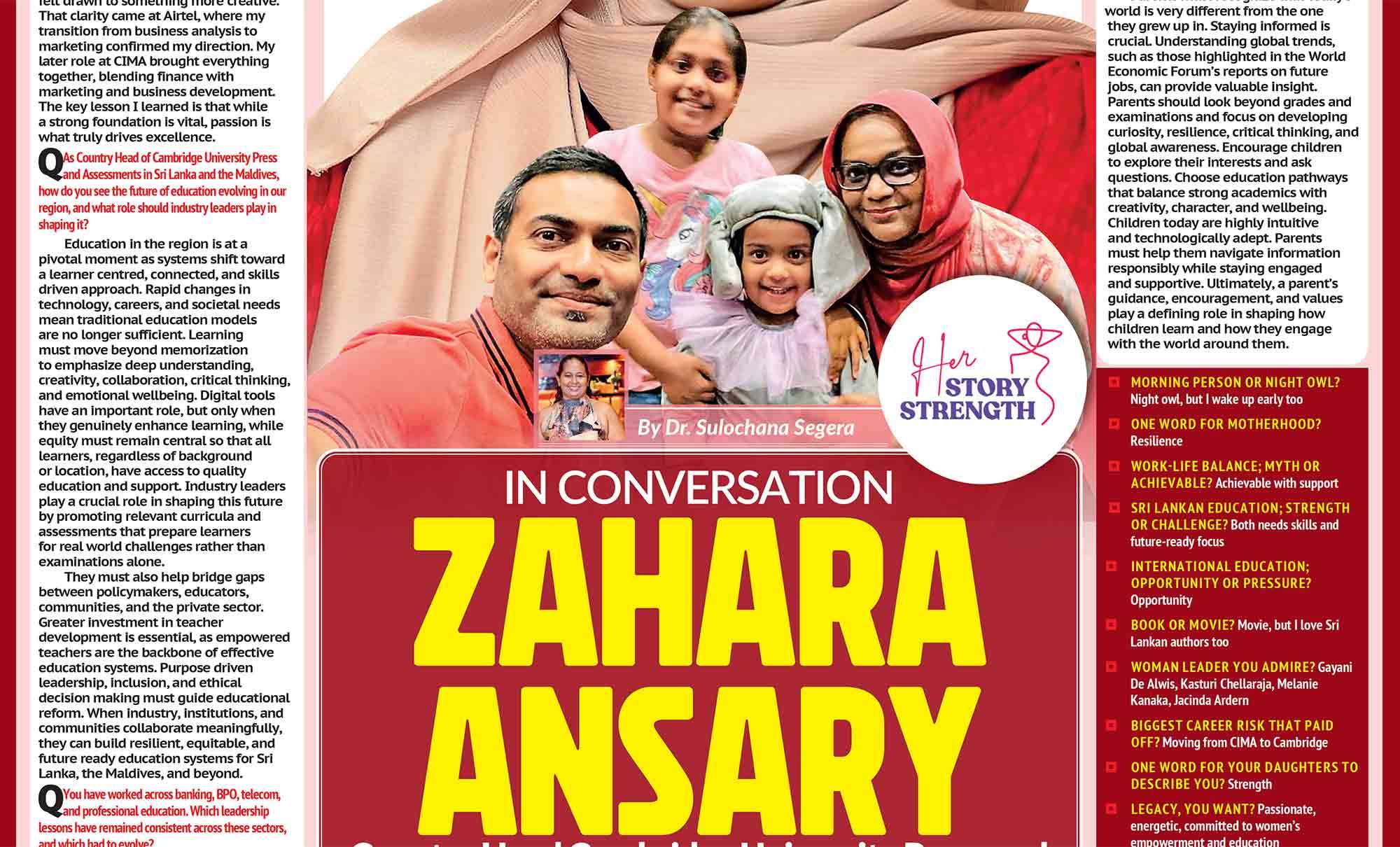

“We are honoured to carry forward a vision deeply rooted in my father’s belief in the power of music to bridge cultures and uplift the human spirit,” said His Highness Prince Rahim Aga Khan, who now leads the Awards alongside his uncle, Prince Amyn Aga Khan.

This year’s edition also carries a sense of remembrance. The late Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, who founded the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) and believed that culture was as vital as sustenance, saw music as a spiritual thread running through the everyday lives of people across the world. His vision now continues through his son, who speaks not only of preservation but of transformation.

The Aga Khan Music Awards are distinct in their scope. While the prize carries a fund of 500,000 dollars, its greater value lies in the opportunities it creates. The laureates gain access to collaborations, commissions, management support, and international visibility, often finding themselves connected to a wider network of mentors and institutions. Past recipients include Malian legend Oumou Sangaré, Indonesian composer Peni Candra Rini, tabla virtuoso Ustad Zakir Hussain, and British-Indian artist Soumik Datta. Each represents a cultural world of their own, yet all share the same commitment to continuity and renewal.

“London feels inevitable,” said Fairouz Nishanova, Director of the Aga Khan Music Programme, which administers the Awards. She was born to Uzbek parents in Sri Lanka. “It has long been a city where traditions from across the globe meet and evolve. The music of the East, from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, has always found new forms here.”

The 2025 edition will also open a new chapter of collaboration with the EFG London Jazz Festival. “We are delighted to open our stages to artists from the Aga Khan Music Awards,” said Festival Director Pelin Opcin. “Not only do we share the Awards’ values of dialogue, collaboration, and connection, but we also celebrate the deep freedoms and expressivity reflected in these distinctive musical styles.”

Nominations for the 2025 Awards opened in April 2024 and were submitted by an international network of performing artists, educators, scholars, producers, and cultural leaders. The winners will be chosen by an independent Master Jury composed of eminent performers, festival directors, and music scholars, ensuring that each selection reflects both artistic excellence and cultural authenticity.

London’s layered identity makes it a natural host for an event that thrives on exchange and reinterpretation. It has long been a meeting point where sound and story evolve, a city that carries the echoes of countless journeys and influences.

What makes the Aga Khan Music Awards unique is that they do not treat traditional music as a relic to be archived. Instead, they ask how these traditions can live in the present moment. From digital reinterpretations of the oud to reimagined Sufi qawwalis and classical raga-infused collaborations, the Awards celebrate innovation without erasure.

Prince Amyn Aga Khan described the initiative as one that “celebrates the full spectrum of music that flourished in cultures across the world, while creating new sounds born from these traditions.” His words reflect the philosophy that heritage and modernity are not opposites, but layers of the same composition.

The Awards form part of the larger Aga Khan Music Programme (AKMP), founded in 2000 as a cultural arm of the AKDN. The Programme works across Central and South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, supporting musicians and educators who preserve local traditions while adapting them for contemporary audiences. For the AKMP, music is not ornamental. It is essential, a vessel for curiosity, understanding, and spiritual connection.

This approach has gradually reshaped the global conversation around heritage. Where many institutions speak of preservation in the language of conservation, the Aga Khan Music Awards speak of evolution. They view music as a living organism, shaped by its listeners as much as by its performers.

As the nominees for 2025 are chosen by the Master Jury, what remains constant is the Awards’ quiet refusal to conform to categories. Genres dissolve, languages merge, and what emerges is something deeply human: the idea that melody can survive displacement, and that rhythm can carry memory.

It is easy, in times like these, to think of music as mere entertainment, something beautiful yet peripheral. The Aga Khan Music Awards remind us otherwise. In their world, a song can be resistance, a rhythm can be remembrance, and a single note can become a way home.

When the lights dim over Southbank this November, the performers who step onto the stage will be more than musicians. They will be archivists of emotion, custodians of centuries, and inventors of what comes next. Their music will not simply be heard, but felt, as a quiet argument that harmony, even now, remains possible.