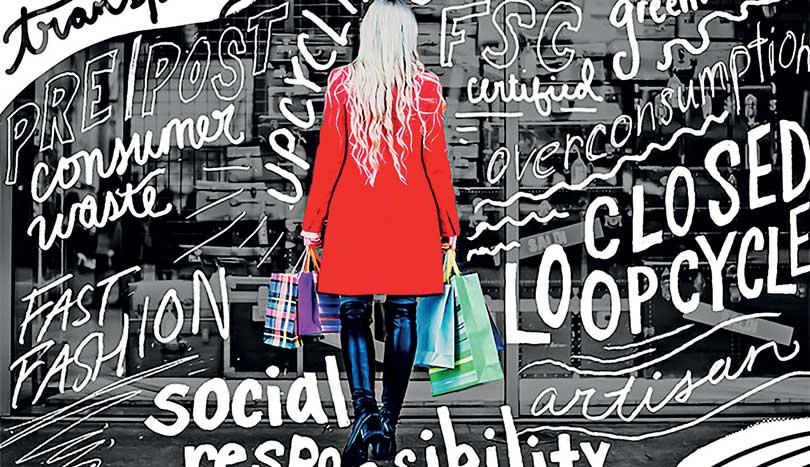

For the past decade, fashion sold us a comforting story. That we could keep shopping, as long as we chose better. Better fabrics. Better labels. Better intentions. Sustainability, we were promised, could be solved at the checkout counter. Buy the “eco” dress. Choose the recycled fabric. Click on resale. Add the carbon offset. Feel lighter, morally, even as the bags got heavier. It was a good story. Too good. Because here we are in 2026, surrounded by more clothes than any generation before us, while fashion’s environmental footprint continues to grow. Emissions are rising. Textile waste is piling up. Consumers are more confused than ever. If sustainability is everywhere, why does nothing feel fixed? The uncomfortable truth is this. We didn’t fail sustainability. Sustainability failed us, or rather, it was repackaged into something it was never meant to be. It became something we could buy, instead of something we had to change.

When sustainability became a shopping category

Sustainability began as a systemic idea. It asked hard questions about limits, labour, extraction, and responsibility. It was never supposed to be easy. It was supposed to be confronting. It was supposed to force us to look at the true cost of convenience. But somewhere along the way, it was absorbed by marketing departments and turned into a product feature. Green tags replaced price tags as the thing to look for. “Conscious collections” appeared next to weekly drops. Recycling bins were placed beside fitting rooms, as if disposal was the same as repair. The underlying message was subtle but powerful. You don’t need to change your behaviour, just your brand choices. And so, sustainability became transactional. We outsourced responsibility to labels, certifications, and slogans. If it said “eco,” we assumed it was enough. It wasn’t. Because a system built on constant production cannot be made sustainable through better packaging. A business model built on overconsumption cannot be fixed by a slightly improved material. Yet that is exactly what we were encouraged to believe.

The myth of “better” consumption

One of the biggest myths we bought into was that buying “better” could cancel out buying more. That if the item was organic, recycled, low impact, or responsibly made, we could keep the same pace of consumption and call it progress. But volume is the real problem. A garment made from organic cotton still carries a carbon footprint. It still requires land, water, energy, processing, transport, and labour. A recycled polyester dress still sheds microplastics. A resale purchase still has transport emissions, especially when shipped individually across borders. Even second-hand, often treated as a sustainability silver bullet, comes with complications. Resale can be powerful when it replaces new consumption. When it genuinely reduces demand for new production. When it extends the life of what already exists. But resale can also increase overall consumption when it encourages people to treat wardrobes as temporary. When it turns clothing into a revolving door, rather than a long-term relationship.

When the mindset becomes “I can buy anything because I can always resell it later.” If buying used simply makes room for buying more new, the net impact shrinks, or disappears. Sustainability was never meant to justify constant renewal. It was meant to challenge it.

Recycling won’t save us and was never meant to.

Another comforting belief is that recycling will take care of fashion’s waste problem. Drop it in a bin, feel responsible, move on. But textile recycling remains deeply limited. Most clothes are blends. Cotton mixed with elastane. Polyester mixed with viscose. Fabrics designed for stretch, softness, performance, or price. They are difficult to separate, expensive to process, and often downcycled into lower value materials. Insulation. Filling. Rags. Sometimes nothing at all. The truth is that less than one percent of clothing globally is recycled back into clothing. Recycling matters. But it was always meant to be a last resort, not the foundation of a system built on disposability. We skipped the harder steps. Wearing longer. Repairing more. Buying less. We leaned on recycling because it allowed us to avoid discomfort. It allowed us to keep the same habits while feeling like we were doing something. But recycling does not erase overproduction. It simply tries to manage the overflow.

What actually helps now: the unglamorous truth

If sustainability marketing thrives on novelty, real impact lives in repetition. The most effective actions available to consumers in 2026 are not exciting, but they are powerful. They are simple. They are unshareable in the way brands prefer. They do not come with a badge. They look like this. Wearing what you already own, again and again. Extending the life of a garment by even nine months can significantly reduce its carbon, water, and waste footprint. Repeat wear is not a failure of style. It is a commitment to reality. It is choosing use over performance. It is valuing function over the thrill of something new.

Repairing instead of replacing.

A mended seam. A reinforced hem. A replaced button. A patch that shows you cared enough to keep it alive. These are small acts with outsized impact. Repair keeps garments in use. It breaks the psychological habit of treating damage as disposal. It interrupts the belief that the moment something is imperfect, it is no longer worth keeping. Buying less, not just “better.” No material innovation can outpace overproduction. Not regenerative cotton. Not bio-based polyester. Not lab grown leather. Not closed loop recycling. Not carbon neutral packaging. Not a new certification. Thoughtful purchasing means fewer items, chosen with intention, not urgency. It means asking if you will wear it thirty times, not if it looks good in one photo. Refusing trends that demand constant reinvention. Trend cycles are not neutral. They are designed to accelerate dissatisfaction. They are engineered to make you feel behind, even when your wardrobe is full. Opting out is a form of consumer power. These actions don’t look impressive on social media. They don’t come with hashtags or limited-edition tags. They don’t feel like a lifestyle upgrade. But they work. Because they reduce demand. They slow the cycle. They reduce production pressure. They keep materials in use. They shift the system from churn to continuity.

The quiet return of responsibility

There’s a shift happening beneath the noise. Consumers are becoming sceptical of sustainability claims and more interested in durability, provenance, and care. This is where the idea of luxury is quietly recalibrating. Not as price or prestige, but as time. Time to make. Time to wear. Time to keep. Real luxury today is knowing who made your clothes and keeping them long enough for that knowledge to matter. It’s owning fewer pieces that carry memory, not just trend relevance. It’s choosing repair over replacement even when replacement is easier. It’s treating clothing as something that belongs in your life, not something that rotates through it. This shift doesn’t ask for perfection. It asks for honesty. Because most people do not live in wardrobes made of ideal fabrics and perfect ethics. Most people live in real bodies, real climates, real budgets, real schedules. They wear what they can afford. They rewear what fits. They choose convenience because life is already heavy. The point is not to become a sustainable saint. The point is to stop letting marketing convince you that your identity depends on constant renewal.

From green guilt to grounded choices

One of the most damaging effects of sustainability as marketing has been guilt. Consumers feel responsible for fixing an industry they don’t control, while being offered solutions that barely move the needle. They are told to do more, research more, buy better, spend more, care more. And when the system keeps burning, they blame themselves. The way forward is not more guilt. It’s clarity. You don’t need a perfectly sustainable wardrobe. You need a real one. One that reflects your life, your body, your climate, your rhythm. One that evolves slowly, not seasonally. One that contains repetition, repair, and the quiet confidence of knowing you don’t need to keep proving you care through what you purchase. Sustainability is not about purity. It’s about reducing harm where you have agency and letting go of the illusion that consumption itself can be the cure. Because consumption was never the solution. It was the engine. So, what should we ask of brands? Consumers alone cannot fix fashion. Responsibility must return to where the power sits. We should demand fewer, better made collections. Transparency without storytelling theatrics. Repair services, not just recycling programs. Design for longevity, not virality. We should demand that brands stop treating sustainability as a marketing aesthetic and start treating it as an operational constraint. We should demand they build for durability, pay fairly, produce less, and stop flooding the world with clothing that is designed to be replaced. But we should also recognise this. Brands respond to behaviour. When demand shifts from novelty to longevity, systems follow. If customers stop rewarding constant drops, brands stop making them. If customers prioritise fit, durability, and repair, brands start building for those things. If customers treat clothing as long term, the market adapts.

The power is not in individual perfection. The power is in collective direction.

The sustainability we actually need the sustainability myth promised ease. What we need now is maturity. A sustainability rooted in limits, not loopholes. In care, not campaigns. In wearing, mending, repeating, and occasionally refusing. Fashion doesn’t need more “conscious” collections. It needs conscious relationships between people and what they own. And perhaps the most radical thing we can do in 2026 is this. Stop asking fashion to make us feel better and start asking it to last. Because sustainability was never about buying the right thing. It was about learning when to stop buying altogether.