We often speak of Sri Lankan identity as if it is ancient, singular, and uncontested. Politicians invoke it, textbooks promote it, and we cling to it as a marker of who we are. But what if this very idea is an illusion? What if our history shows that Sri Lanka has never been one thing, but many things; a crossroads of peoples, myths, and cultures?

The Original Invaders

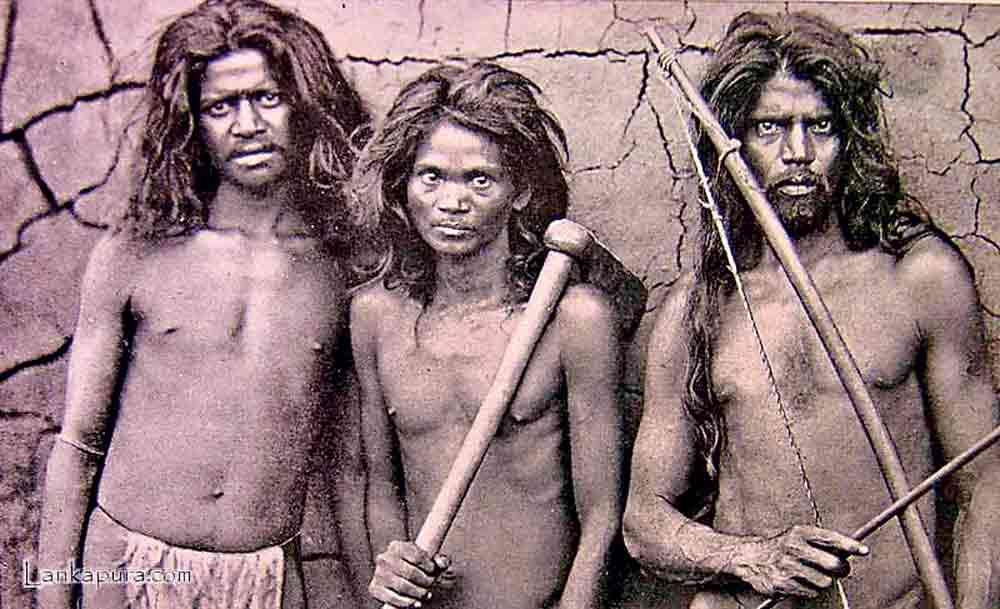

Our story begins with Prince Vijaya. The chronicles tell us that he arrived on our shores from India around the 5th century BCE, took Kuweni, a local queen, as his consort, and founded the Sinhalese people. It is celebrated as the birth of our nation. But what does it mean if we look closer? It means our “origins” were not native at all. They were the story of outsiders arriving, marrying into existing communities, and imposing a new identity. Long before Vijaya, this island was already inhabited by the Veddas, Sri Lanka’s indigenous people who lived by hunting, gathering, and small-scale cultivation. Their language, rituals, and oral traditions tell of a way of life that predates recorded history. Even today, though much diminished, Vedda communities survive in Dambana and a few other enclaves. The Vedda identity complicates the myth of a singular Sinhala origin. It suggests that the Sinhalese themselves were not the first Sri Lankans. They were, like so many after them, part of a wave of migrants and conquerors who settled on this island. In short, Sri Lanka has always been layered, always been diverse, and in flux.

Our story begins with Prince Vijaya. The chronicles tell us that he arrived on our shores from India around the 5th century BCE, took Kuweni, a local queen, as his consort, and founded the Sinhalese people. It is celebrated as the birth of our nation. But what does it mean if we look closer? It means our “origins” were not native at all. They were the story of outsiders arriving, marrying into existing communities, and imposing a new identity. Long before Vijaya, this island was already inhabited by the Veddas, Sri Lanka’s indigenous people who lived by hunting, gathering, and small-scale cultivation. Their language, rituals, and oral traditions tell of a way of life that predates recorded history. Even today, though much diminished, Vedda communities survive in Dambana and a few other enclaves. The Vedda identity complicates the myth of a singular Sinhala origin. It suggests that the Sinhalese themselves were not the first Sri Lankans. They were, like so many after them, part of a wave of migrants and conquerors who settled on this island. In short, Sri Lanka has always been layered, always been diverse, and in flux.

Legends Older than History

Adding to this complexity are the myths that run parallel to history. Some claim Sri Lanka was once part of the lost continent of Kumari Kandam, linking us to Tamil and Dravidian legends. Others tie us to the epic of Ravana, portraying him as a mighty king whose realm was Lanka long before Vijaya’s arrival. Whether myth or fact, these stories matter because they remind us that our origins are neither simple nor uncontested. They suggest layers of identity, some lost to time, others preserved in fragmentary traditions.

We are living a paradox. We are the daughters of the first female prime minister in the world, a fact we wield like a shield in international forums. Yet, that legacy has fossilized into a convenient statue we dust off for speeches while the living, breathing women of this nation are being failed by every pillar designed to protect them. This is not a government problem; it is a national cancer.

Centuries of Invasions and Exchanges

Even after Vijaya, Sri Lanka never developed in isolation. Waves of migration from India continued, shaping language, religion, and governance. The island’s location in the Indian Ocean ensured it was always connected to larger currents of trade and conquest. The Chola invasions of the 10th and 11th centuries reshaped administration and introduced new communities that blended into the island’s ethnic fabric. Arab and Persian traders settled along the coasts, bringing new religious ideologies. South Indian migrations enriched language, religion, and culture. The Portuguese, Dutch, and British came much later, but the process was the same: outsiders arriving, reshaping the island, and leaving behind traces that never disappeared. The Portuguese gave us Catholicism and names like Silva and Fonseka. The Dutch contributed Roman-Dutch law and the Burgher community. The British imposed English, railways, plantations, and modern education. Even African slaves brought by the Portuguese left a lasting legacy, with the Kaffirs of Puttalam still singing in their unique creole tongue. This is not a story of purity. It is a story of mixture.

A Hotchpotch or a Heritage?

So, what does it mean to be Sri Lankan today? Are we Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, or Christian? Are we defined by kiribath and peraheras, or by lamprais and isso wade? When we look at Sri Lanka honestly, we see not a pure, continuous identity but a melting pot. We are descendants of Veddas, of Indian migrants, of South Indian invaders, of Persian and Arab traders, of Portuguese and Dutch colonialists, of British administrators, of African slaves brought centuries ago. In truth, we are all of these. To claim a singular “Sri Lankan identity” is to deny the very richness of our history. And globalisation has only deepened the question. Sri Lankans who left decades ago return to a country they sometimes no longer recognise; one which is westernised, commercialised, and fast-paced. International schools and shopping malls sit alongside ancient chaithyas and kovils. English is spoken more widely, yet so is the nostalgia for “authentic culture.” But what is authenticity? A Vesak lantern? A Tamil kooththu? A Hindu kolam? An Afro-Portuguese baila? Or a mix of them all?

The Dangerous Myth of Purity

Perhaps the greatest betrayal is not colonialism but the myth we still tell ourselves, that there is a pure, singular identity to be preserved. History says otherwise. From Vijaya and Kuweni to the Cholas, Portuguese, Dutch, and British, our story is one of layers, crossings, and exchanges. To insist on purity is not only false, but also dangerous. It fuels exclusion, blinds us to our shared heritage, and denies the strength that lies in our diversity. If Part I of this story was about the political betrayal of 1815, then Part II is about the cultural betrayal we commit against ourselves when we deny our layered identity. Sri Lanka is not a monolith. It is a mosaic. To be Sri Lankan is not to trace a single unbroken line back to Vijaya or Ravana. It is to accept the mixture, the contradictions, the overlaps, and to find pride in them. That, perhaps, is our true identity.

Epilogue

Understanding our legacy is not just about learning history. Rather, it is about discovering who we are. When students and young people know where they come from, they gain the confidence to shape their futures. Our past, with all its complexity, teaches us resilience, identity, and pride. Sri Lanka’s story is not one of purity, but of diversity, of kings and rebels, traders and settlers, colonisers and freedom fighters. When we embrace this truth, we no longer feel uncertain about who we are. Instead, we stand stronger, knowing we are part of a long, rich, layered heritage. For parents and students alike, this knowledge is powerful. It reminds us that leadership begins with self-awareness, that confidence grows when we understand our roots, and most importantly, that real strength comes not from denying the past, but from learning from it. To know our legacy is to walk into the future with purpose.