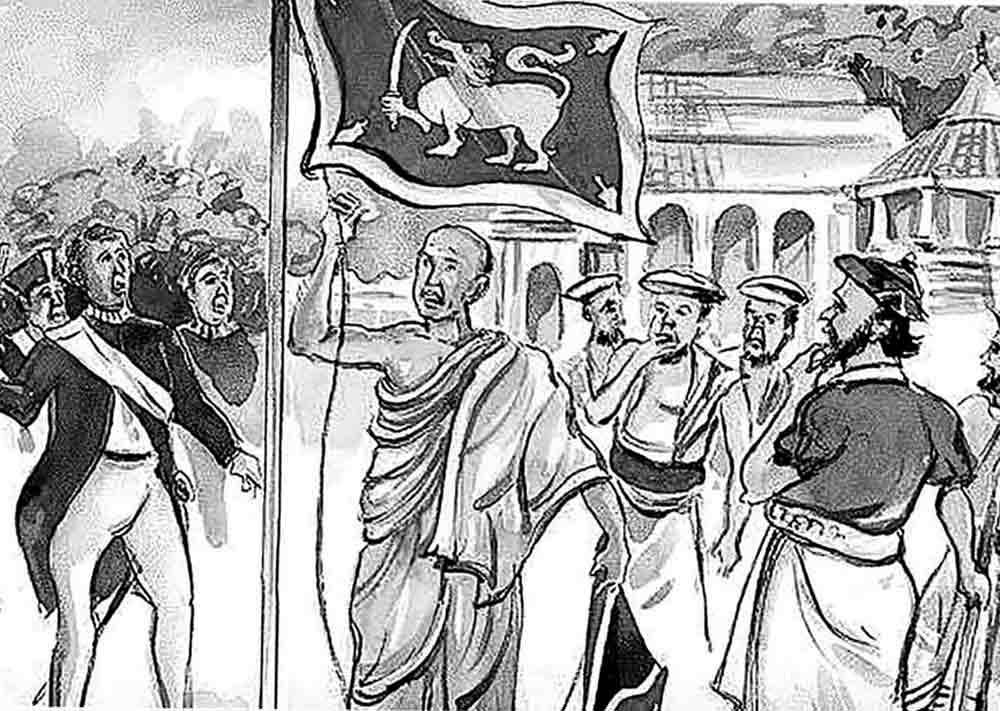

On March 2, 1815, a group of Kandyan chiefs gathered in the Royal Audience Hall in the precincts of the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Kandy to sign what would become one of the most consequential documents in Sri Lankan history: the Kandyan Convention. With their signatures, sovereignty in Ceylon which had passed from Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa, and Dambadeniya to Kandy, was handed over to a foreign power. For the first time, the island came fully under colonial rule.

The significance of that day cannot be overstated. Unlike the Portuguese and the Dutch, who occupied coastal strongholds, the British managed to secure the last independent Sinhalese kingdom without a decisive battlefield victory. They achieved this through intrigue, manipulation, and the discontent of Kandyan nobles who had turned against their king, Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe whose rule had become deeply unpopular. It is said that he mistrusted the aristocracy – understandable when you consider that he was a Nayak king of Telugu origin, “imported”, so to speak, from Madurai, India to rule the Kandyan kingdom. Not surprisingly, the sentiments were reciprocated by the Kandyan chieftains. Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe, with his harsh punishments, and his alienation of the very chiefs whose loyalty had kept the Kandyan kingdom intact, more or less divided the court. Resentment thus brewed, and ambition gave way to espionage. The chiefs who negotiated with the British were not thinking of sovereignty or of the people. They were thinking purely of themselves. Many foolishly believed that, under British rule, they could preserve their privileges, their lands, and their influence, whilst shedding a monarch they despised.

The significance of that day cannot be overstated. Unlike the Portuguese and the Dutch, who occupied coastal strongholds, the British managed to secure the last independent Sinhalese kingdom without a decisive battlefield victory. They achieved this through intrigue, manipulation, and the discontent of Kandyan nobles who had turned against their king, Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe whose rule had become deeply unpopular. It is said that he mistrusted the aristocracy – understandable when you consider that he was a Nayak king of Telugu origin, “imported”, so to speak, from Madurai, India to rule the Kandyan kingdom. Not surprisingly, the sentiments were reciprocated by the Kandyan chieftains. Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe, with his harsh punishments, and his alienation of the very chiefs whose loyalty had kept the Kandyan kingdom intact, more or less divided the court. Resentment thus brewed, and ambition gave way to espionage. The chiefs who negotiated with the British were not thinking of sovereignty or of the people. They were thinking purely of themselves. Many foolishly believed that, under British rule, they could preserve their privileges, their lands, and their influence, whilst shedding a monarch they despised.

As for the British, they played their part masterfully. They promised to uphold Buddhism, protect local customs, and respect the rights of the nobility. In reality, these were hollow reassurances. Within years, those same nobles would learn that the British had no intention of being bound by such promises. The rebellion of 1818 revealed the truth. Only three years after the signing of the Kandyan Convention, the Kandyan peasantry rose up in arms, disillusioned with colonial promises. The response was brutal. Entire villages were burned, harvests destroyed, populations displaced. This was not accidental cruelty but deliberate policy. The British understood the power of division.

They elevated some chiefs, punished others, and drove a wedge between leaders and the people. Over time, they extended this philosophy across the island: managing communities separately, enforcing ethnic and class distinctions, and ensuring that no unified resistance could form. In short, it was a classic case of “divide and conquer”, and it was this strategy that allowed them to hold control until independence in 1948. What Did Colonialism Leave Behind?

There are those who argue that British colonialism brought progress - railways, roads, plantations, schools, and the English language. But we must ask: progress for whom?

The railways were built to move tea, coffee, and rubber from plantations to ports, enriching the empire, not the villagers of the hill country. Roads were laid to serve garrisons and promote administrative efficiency. Schools were established, but only a few benefited from English education, creating an elite that distanced itself from the masses.

The economic legacy was one of dependency: plantation monocultures vulnerable to global markets. The social legacy was inequality, with English-speaking elites gaining access to power while the majority remained voiceless.

Most damaging of all was the cultural legacy. A people who had been sovereign for over two millennia now found themselves questioning their own traditions. Local systems of governance and justice were dismantled. Language and learning were overshadowed by imported models. Confidence in our own ways of life began to erode.

Of course, colonialism did not arrive on an empty island. Long before the British, Sri Lanka had been shaped by outsiders. The Portuguese brought Catholicism along with surnames like Perera and Fernando. The Dutch left behind Roman-Dutch law and the Burgher community. Traders from Arabia, Persia, and India had already introduced new faiths and communities centuries before.

But the British were different in scale and permanence. They did not just touch the coasts; they penetrated the highlands, reshaped the economy, and redefined politics. What had once been a proud and independent kingdom was now a colony integrated into an empire that spanned the globe.

Do We Regret the Kandyan Convention?

Two centuries later, the Kandyan Convention forces us to ask difficult questions. Was it an act of betrayal by the chiefs? Was it a tragic inevitability, given the pressures of empire building? Or was it both?

What is clear is that 1815 changed the trajectory of the island. It ended sovereignty, undermined cultural confidence, and introduced systems that still shape our politics, education, and society. Colonialism altered how people saw themselves. Traditional systems of governance were weakened. Local practices were often dismissed as “backward.” Pride in indigenous culture gave way, in many circles, to admiration for Western norms. Even today, we see the long shadow of those attitudes.

When we look at the Kandyan Convention today, it is tempting to say we regret it. But perhaps regret is not enough. The real lesson lies in recognising how easily sovereignty can be lost when leaders place personal agendas above collective good, and when promises of “progress” mask hidden costs.

The “great betrayal” of 1815 was not only political. It was cultural and spiritual, a surrender of confidence in ourselves. And its consequences continue to echo into our present. British colonialism left us infrastructure, institutions, and the English language. But it also left us divided, uncertain, and searching for who we are. Today, as in 1815, the real question is whether we can define our identity on our own terms.

Read next Wednesday’s edition of The Sun for THE GREAT BETRAYAL, PART II