Introduction: A City of Glory, A City of Ruin

Introduction: A City of Glory, A City of Ruin

Polonnaruwa dazzled in its prime. Its reservoirs glittered like inland seas, its Buddhas stood serene in stone, and its kings styled themselves as both protectors of Buddhism and masters of conquest. Yet within a century of Parākramabāhu I’s death in 1186, the city had fallen into ruin. The jungle crept over palaces, irrigation tanks silted, and the kingdom fractured into rival courts. The decline was not the work of foreign enemies alone. Behind the collapse lay scandal: assassinations, betrayals, queens whose alliances determined succession, generals who switched loyalties, and kings who squandered resources. To trace the fall of Polonnaruwa is to see how dynastic ambition, personal desire, and political treachery eroded even the most dazzling achievements.

I. The Inheritors of Parākramabāhu: Fragile Thrones

Parākramabāhu the Great (1153–1186) embodied the apex of Polonnaruwa’s ambition. He unified the island, reformed the sangha, built colossal reservoirs, and even launched expeditions abroad. But he left no stable succession. His authority had rested on charisma, conquest, and hydraulic grandeur; not on clear lines of inheritance. After his death, the throne passed rapidly from one ruler to another. Vijayabāhu II reigned for a year before being assassinated. Mahinda VI briefly claimed the throne in 1187, only to be overthrown by Nissankamalla. The Cūḷavaṃsadescribes these kings in moral terms, as weak, indulgent, or impious, but behind such rhetoric lies the reality of succession without consensus. As historian H. C. Ray observed, the chronicles often veil political instability in moral language, casting dynastic struggles as failures of virtue.

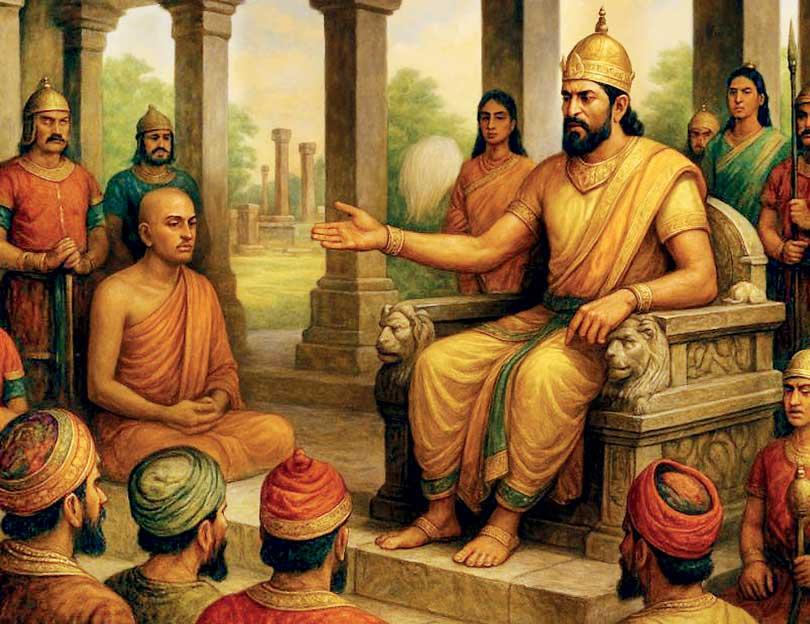

II. Nissankamalla: The Kalinga Pretender

Nissankamalla (1187–1196), a prince from Kalinga in eastern India, seized the throne through a mixture of military force and royal marriage. His inscriptions litter the ruins of Polonnaruwa: bombastic declarations of generosity, piety, and conquest. He claimed to have fed the poor, endowed monasteries, and subdued rival kings. But as Senake Bandaranayake and other epigraphers note, Nissankamalla’s texts reveal less about actual victories than about a king obsessed with image. His boasts of feeding the entire island may have been propaganda, but the expenditures were real, draining the treasury and destabilizing royal finances. The Cūḷavaṃsa even records him as a “self-exalting monarch,” whose hunger for prestige outweighed prudence. Nissankamalla’s reign illustrates the fragile legitimacy of Polonnaruwa: a foreign-born king could hold the throne only by theatrics of kingship, lavish donations, extravagant claims, and monumental inscriptions, that masked but did not resolve dynastic uncertainty.

III. Queens, Lovers, and Court Intrigue

Succession in Polonnaruwa was shaped as much in the palace as on the battlefield. Royal women, often ignored by chronicles, played decisive roles. Marriages cemented alliances; queens and concubines maneuvered to elevate their sons; rival factions found champions within the harem. One example is the contested reign of Sahassa Malla (1200–1202). His brief kingship owed more to matrimonial alliances than to military strength. The Cūḷavaṃsa dismisses him as a king “addicted to pleasure, unfit for sovereignty,” but such judgments hint at deeper anxieties: that legitimacy derived not from ability but from palace influence. As K. Indrapala has argued, repeated descriptions of royal “indulgence” in chronicles reflect more than moral censure, they expose the structural role of women and courtiers in shaping dynastic succession. We glimpse, too, the possibility of scandalous liaisons destabilizing the throne. Though veiled by monastic chroniclers, later traditions speak of queens favouring lovers or court favourites, undermining kings already precariously placed. Whether literal or rhetorical, these tales reveal the suspicion that desire itself was political in Polonnaruwa.

IV. Generals and Betrayal: The Militarisation of Politics

As royal succession grew unstable, generals became kingmakers. Armies no longer served the throne unconditionally; they could make and unmake rulers. The worst came in the early 13th century, when Polonnaruwa was fractured by repeated coups. When Magha of Kalinga invaded in 1215, he arrived with South Indian mercenaries. Yet his success owed as much to Sinhala disunity as to foreign arms. The Cūḷavaṃsa condemns him as a despoiler of temples and oppressor of monks, but G. C. Mendis notes that local betrayal enabled his conquest. Generals defected, nobles shifted allegiance, and Polonnaruwa collapsed without unified resistance. The city that once launched expeditions abroad was undone by its own commanders at home. Treason, more than invasion, sealed its fate.

V. Case Study: The Collapse of the Hydraulic State

Political scandal had ecological consequences. The great reservoirs, especially the Parakrama Samudra, required constant upkeep. Sediment cores studied by Sri Lankan archaeologists show a marked decline in maintenance during the early 13th century, coinciding with the succession crises. Without coordinated desilting, canals clogged, floods followed, and harvests failed. Leslie Gunawardana’s Robe and Plough demonstrates how monastic landlords, once integrated into the hydraulic bureaucracy, lost alignment with the crown. As kings fell, the fragile partnership between throne and sangha dissolved. The result was ecological decline, a tangible marker of scandal translated into famine. Here Polonnaruwa reveals the intimate link between politics and environment: the betrayal of generals and the indulgence of kings were not abstract failures but concrete ones, written into failed harvests and starving populations.

VI. Nissankamalla’s Successors: A Parade of Pretenders

After Nissankamalla, Polonnaruwa endured a dizzying carousel of monarchs. Sahassa Malla, Lilavati, Lokissara, Queen Kalyanavati, each ruled briefly, often installed or deposed by ambitious generals. The Cūḷavaṃsa describes some as pawns, others as tyrants. Modern scholars stress the structural chaos: no dynasty could establish stability because succession was contested from every quarter, bloodline, marriage, army, and monastic endorsement.

Lilavati (1197–1200, restored twice later) stands out as one of the few queens to reign in her own right. The chroniclers describe her as “righteous and devoted,” yet her rule too was fragile, sustained by shifting military support. The spectacle of a queen ruling directly is significant: it suggests both the empowerment of royal women and the desperation of a polity unable to find male consensus.

VII. The Fall into Silence

By the mid-13th century, Polonnaruwa was untenable. Capitals shifted south, first to Dambadeniya, then to Yapahuwa, while the once-mighty city decayed. The jungle reclaimed its palaces, but memory preserved its scandals: assassinations, lovers, usurpers, traitors. The chronicles mourned its collapse as a moral failure. Archaeology shows it as an ecological one. Historians today view it as both: a convergence of dynastic intrigue, elite betrayal, and environmental neglect.

Conclusion: A Medieval Game of Thrones

Polonnaruwa’s story is less a straight line of decline than a spiral of scandal. Kings rose and fell by assassins’ blades, by the favours of queens, or by the betrayal of their generals. Hydraulic marvels crumbled when political order broke down. Even as serene Buddhas smiled from the Gal Vihāra, the palace rang with plots and the council chamber with treachery. It is tempting to compare this to modern fantasy: a medieval Game of Thrones played out in the heart of Sri Lanka. But the stakes were real. Famine, invasion, and ruin were the consequence of scandal and succession. Polonnaruwa remains a reminder that kingdoms collapse as often from within as from without, and that glory, once fractured by lovers and traitors, can vanish into forest silence.