Myth, Memory, and the Politics of Lanka’s Demon King

- In the end, Ravana may remain unverifiable. There are no inscriptions that bear his name, no coins that link him to a dynasty. But history is not only what we can excavate. It is also what we remember, what we choose to forget, and what we revive. Ravana exists in a liminal space - between myth and memory, villainy and virtue, demonhood and kingship.

1.Part I of a Three-Part Series

Ramayana Reconsidered

A New Lens on an Old Epic

This article inaugurates a three-part exploration of the Ramayana, focusing not on the epic's central hero but on its contested characters. Figures who inhabit the boundary between myth and history. Across the next three weeks, we will examine three central personalities: Ravana, Hanuman, and Sita. Each of them, in different ways, has been interpreted, appropriated, and transformed by Sri Lankan memory. We begin, fittingly, with Ravana. The demon-king of Lanka, the antagonist of Rama, and perhaps the most controversial figure in South Asian epic tradition. In the Indian imagination, he is the emblem of hubris and adharma. In the Sri Lankan landscape, however, his figure is more ambiguous, even reverent. Ravana may not appear in our island’s chronicles, but he lives on in waterfalls, caves, and nationalist retellings. And that absence, too, tells a story.

2.The Ramayana’s Lanka and Its Demon King

Composed across several centuries between roughly 500 BCE and 300 CE, the Ramayana envisions Lanka as the fortified island kingdom of Ravana, a rakshasa of extraordinary power, learning, and ritual skill. With ten heads, an airborne chariot, and mastery of Vedic knowledge, Ravana is no mere brute. He is a tragic overreacher, whose defeat by Rama stands as the cosmic restoration of order. Geographically, the epic’s Lanka has long been associated with modern-day Sri Lanka. The sea crossing described in the text, the prominence of Mount Trikuta, and later Sanskrit and Tamil commentaries all reinforce this claim. But not all agree. Scholars such as Hermann Jacobi have argued that Lanka in the Ramayana may not have been a real place but rather a symbolic otherworld, representing moral and ritual inversion. The Sri Lankan Pali chronicles, notably the Mahāvamsa, composed in the 5th century CE, do not mention Ravana at all. This is not an oversight. It is a deliberate exclusion. The Mahāvamsa’s author, Mahanama Thera, had a project: to construct a narrative of Sinhala identity rooted in Buddhist kingship and the arrival of Prince Vijaya from India. Ravana, a Brahmanic figure steeped in ritual power, would not have fit the ideological structure of that story.

3.The Landscape of Memory

And yet, Ravana refuses to vanish. In the central hills, the southern plains, and among the echoes of village lore, Ravana lives on. Sri Lanka’s geography is studded with places bearing his name: Ravana Ella, the cascading waterfall near Ella Pass, Ravana Guhā, a cave system said to have served as his retreat, and even Yākhā Guhā, where some believe his allies once lived. Colonial-era surveyors in the 19th century documented these toponyms with curiosity, but usually dismissed them as local superstition. The stories, however, persisted. In some retellings, Ravana was a wise physician who used the caves to prepare ayurvedic elixirs. In others, he was a noble king betrayed not by his own flaws but by divine intervention.

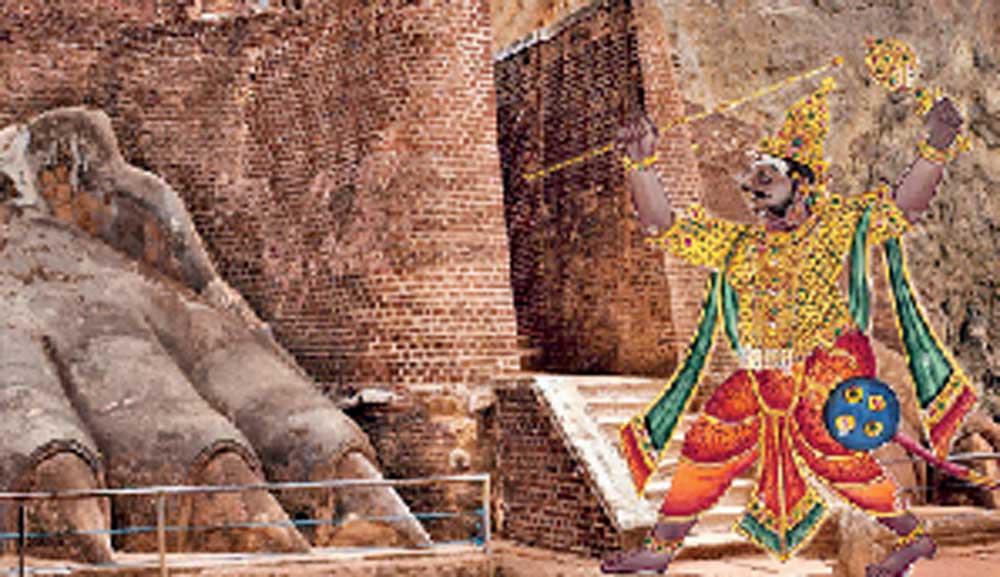

At Sigiriya, popular reinterpretation has cast the ancient fortress not as Kassapa’s citadel, but as Ravana’s palace, complete with murals and engineering marvels that testify to his sophistication. These claims are not supported by archaeological consensus. But they reflect something more important than verification. They reflect the popular memory of sovereignty, the desire to see in Ravana a rightful king rather than a defeated villain.

Demon or Patriarch?

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Ravana’s image has shifted dramatically. No longer simply a demon, he has become a figure of national pride. Sinhala Buddhist revivalist groups, and even some Tamil communities, have embraced Ravana as a symbol of indigenous power. Writers such as D. M. P. B. Herath and Manik Sandrasagara have produced works arguing for Ravana’s historicity and his status as a pre-Vijayan ruler. These retellings do not merely seek historical clarification. They are acts of political memory, asserting Lanka’s autonomy from Indian cultural dominance. This phenomenon is not isolated. Across India, especially in parts of Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and among certain tribal groups, Ravana is worshipped as a wise and just ruler. In these reinterpretations, the Ramayana becomes a contested text, and Ravana becomes a symbol of resistance. Such reframing aligns with broader theories in postcolonial historiography. As Benedict Anderson famously argued, nations are “imagined communities.” And the imagining of Ravana as a hero rather than a demon is part of Sri Lanka’s ongoing redefinition of itself.

4.Why the Silence?

Why did the authors of the Mahāvamsa choose not to include Ravana? Here, the anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillotis instructive. In his work on the production of history, he notes that “silences enter the process of historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation, fact assembly, fact retrieval, and retrospective significance.” Ravana’s omission is not just a gap. It is an ideological move. The Theravāda Buddhist order, closely aligned with the ruling elite of Anuradhapura, sought to present a history that linked Lanka to the Buddha’s presence and India’s moral authority. Ravana, with his Vedic sacrifices and cosmic ambitions, threatened that vision. To include Ravana would have been to accept a different origin story. One that suggested the island was once ruled by non-Buddhists. Perhaps even by those who defied divine will.

Conclusion: Between Chronicle and Cave

In the end, Ravana may remain unverifiable. There are no inscriptions that bear his name, no coins that link him to a dynasty. But history is not only what we can excavate. It is also what we remember, what we choose to forget, and what we revive. Ravana exists in a liminal space - between myth and memory, villainy and virtue, demonhood and kingship. And in that space, he has become more powerful than any chronicle could contain. As we continue this series in the coming weeks, we will move from Ravana to Hanuman, the bridge-leaping devotee who bound Lanka and India, and then to Sita, whose body and silence have been at the centre of ethical and political interpretations for millennia. But for now, in the first telling, we return to the hills, to the caves, to the waterfall whose roar bears a forgotten king’s name.

- In the 20th and 21st centuries, Ravana’s image has shifted dramatically. No longer simply a demon, he has become a figure of national pride. Sinhala Buddhist revivalist groups, and even some Tamil communities, have embraced Ravana as a symbol of indigenous power.