In tracing the moral lineage of non-violent resistance, one finds a remarkable thread that winds its way from the railways of Pietermaritzburg to the streets of Montgomery, and finally, to the prisons of Robben Island. It is a thread spun from courage, conscience, and an unyielding faith in human dignity. If Gandhi taught the world the moral power of truth, and Martin Luther King Jr. translated it into the language of modern democracy, then Nelson Mandela embodied its endurance: the ability of conscience not only to resist injustice but to reconcile with it.

Mandela’s South Africa was, in many ways, the crucible in which the ideals of Gandhi and King were tested under the harshest conditions imaginable. Apartheid was not merely a policy. It was a complete architecture of separation, designed to dehumanize and divide. Instituted formally in 1948, apartheid sought to ensure white dominance in every sphere of life, from political, to economic, and to social. It classified South Africans into rigid racial categories: white, black, coloured, and Asian, each assigned to their own schools, hospitals, residential zones, and even park benches. Land was unevenly divided - 87 percent reserved for whites, and the remainder for millions of blacks who were herded into impoverished “homelands.” Black South Africans were denied the right to vote, to work freely to study in decent schools, or even to walk in certain streets without carrying a passbook. It was a system that sought to extinguish equality at its root, by controlling not just movement but the very imagination of freedom.

It was in this world that Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela came of age. Born in 1918 in the rural village of Mvezo in Umtata, he was raised in the traditions of the Thembu people but educated in the ways of the coloniser. At Fort Hare University and later in Johannesburg, Mandela came face to face with the contradictions of a society that preached civilization yet practiced cruelty. It was there that his political awakening began. Influenced by thinkers across continents, from Marx to Gandhi, Mandela came to see that freedom was not a privilege but a birthright, and that the struggle for it demanded both discipline and sacrifice.

Gandhi’s shadow loomed large over South Africa. It was in this same land, half a century earlier, that Gandhi had forged satyagraha to confront the injustices faced by Indians under colonial rule. Mandela would later acknowledge this inheritance, remarking that “the spirit of Gandhi may well be a South African spirit”. But where Gandhi’s satyagraha had sought to melt the oppressor’s heart through moral appeal, Mandela’s generation would eventually face an enemy immune to persuasion.

For years, Mandela and his comrades in the African National Congress (ANC) embraced nonviolent protest. They organized strikes, boycotts, and the famous Defiance Campaign of 1952, during which thousands deliberately violated apartheid laws. But the massacre at Sharpeville in 1960, when police opened fire on unarmed demonstrators, killing 67, changed everything.

“At the time”, Mandela later reflected, “we had no alternative but to answer violence with violence”. The ANC established an armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, the Spear of the Nation, of which Mandela became a founding member.

This marked not an abandonment of conscience, but a painful evolution of it. Mandela’s resistance remained disciplined and purposeful; sabotage was directed at infrastructure, not people. Even in defiance, he held to a deeper moral code: the belief that freedom gained through hatred would not be freedom at all. His famous words at the Rivonia Trial in 1964 captured both defiance and devotion to principle: “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities… if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die”.

He would spend the next 27 years in prison for that ideal. On Robben Island, the man who entered as a militant emerged as a statesman. Denied books, confined to a cell barely large enough to stretch out in, forced into hard labour in the limestone quarries, Mandela nonetheless refused to allow bitterness to take root. Instead, he turned his imprisonment into a classroom. He studied the language of his jailers, read widely, debated with fellow prisoners, and kept alive the moral flame that the apartheid regime sought to extinguish. “Man’s goodness”, he would later write, “is a flame that can be hidden but never extinguished”.

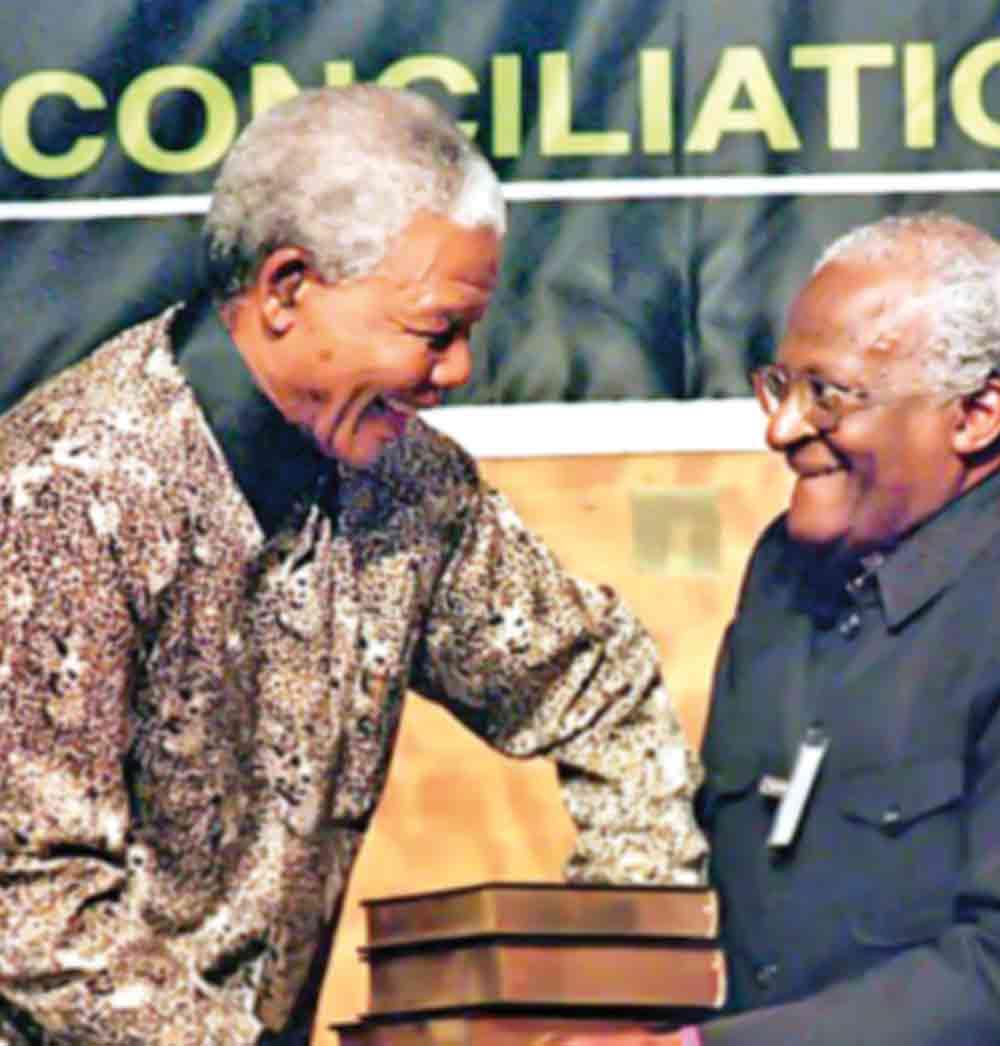

When he finally walked free on February 11, 1990, the world saw not a broken man but one whose spirit had been tempered like steel. Within four years, Mandela would lead South Africa into its first multiracial elections, standing not as a victor over his enemies but as a reconciler among them. His inauguration as President in 1994 marked not just a political transition but a moral one, from vengeance to forgiveness, from exclusion to inclusion. He chose, as Gandhi had, to believe in the possibility of redemption. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established under his leadership, embodied this vision. It did not seek to erase the past but to confront it with honesty, inviting victims and perpetrators alike to speak their truths.

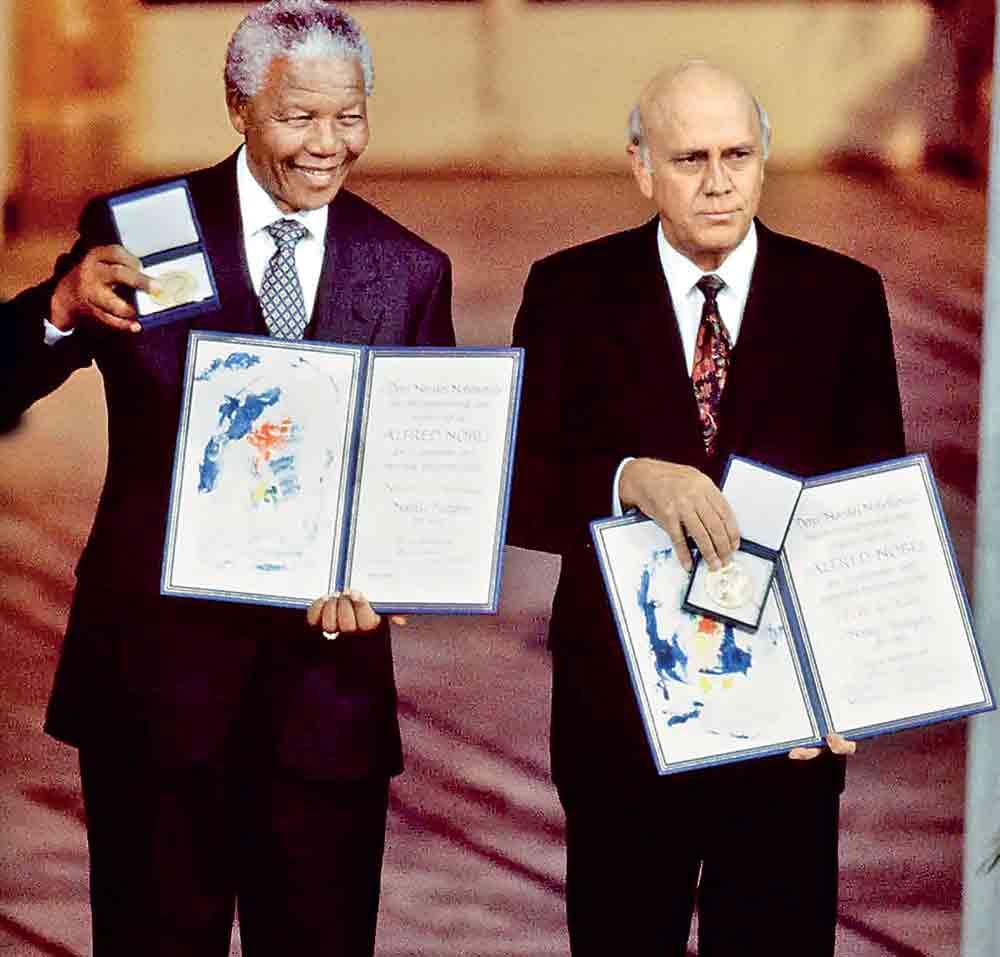

It is tempting to remember Mandela as a saintly figure, but his greatness lay precisely in his humanity, in the conscious choice to forgive without forgetting, to lead without dominating, to serve without seeking power for its own sake. His presidency was marked by humility and moral purpose. He donated half his salary to children’s causes, established the Nelson Mandela Foundation, and never lost touch with the ordinary people whose struggles had shaped him. In 1993, he shared the Nobel Peace Prize with F.W. de Klerk, the man who had once represented the system that imprisoned him - a gesture that symbolized the triumph of conscience over conflict.

Mandela’s life thus completes the moral triangle begun by Gandhi and King. Each stood at a crossroads of history, confronting a different face of oppression but guided by the same inner compass. Gandhi sought to awaken the conscience of empire; King appealed to the conscience of democracy; Mandela healed the conscience of a nation. Together, they remind us that moral leadership is not born in comfort but in struggle, and that true freedom requires not only justice but generosity of spirit.

For today’s learners, their stories offer more than historical inspiration. They present a model of education itself: an education of conscience. Mandela understood this deeply. “Education”, he said, “is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world”. It was through education, formal and moral, that he built the resilience to endure prison and the wisdom to rebuild a nation.

As the echoes of Gandhi and King resounded through his life, Mandela left behind an echo of his own, one that continues to stir the global conscience. It is the echo of a man who refused to hate, who chose dialogue over division, and who believed, against all odds, that the human spirit is stronger than the systems that seek to chain it. In the quiet cadence of his example, we hear the same moral truth that linked three continents and three lives: that power without conscience destroys, but conscience with courage redeems.

Read next Wednesday’s edition of The Sun for ECHOES OF CONSCIENCE, PART III.