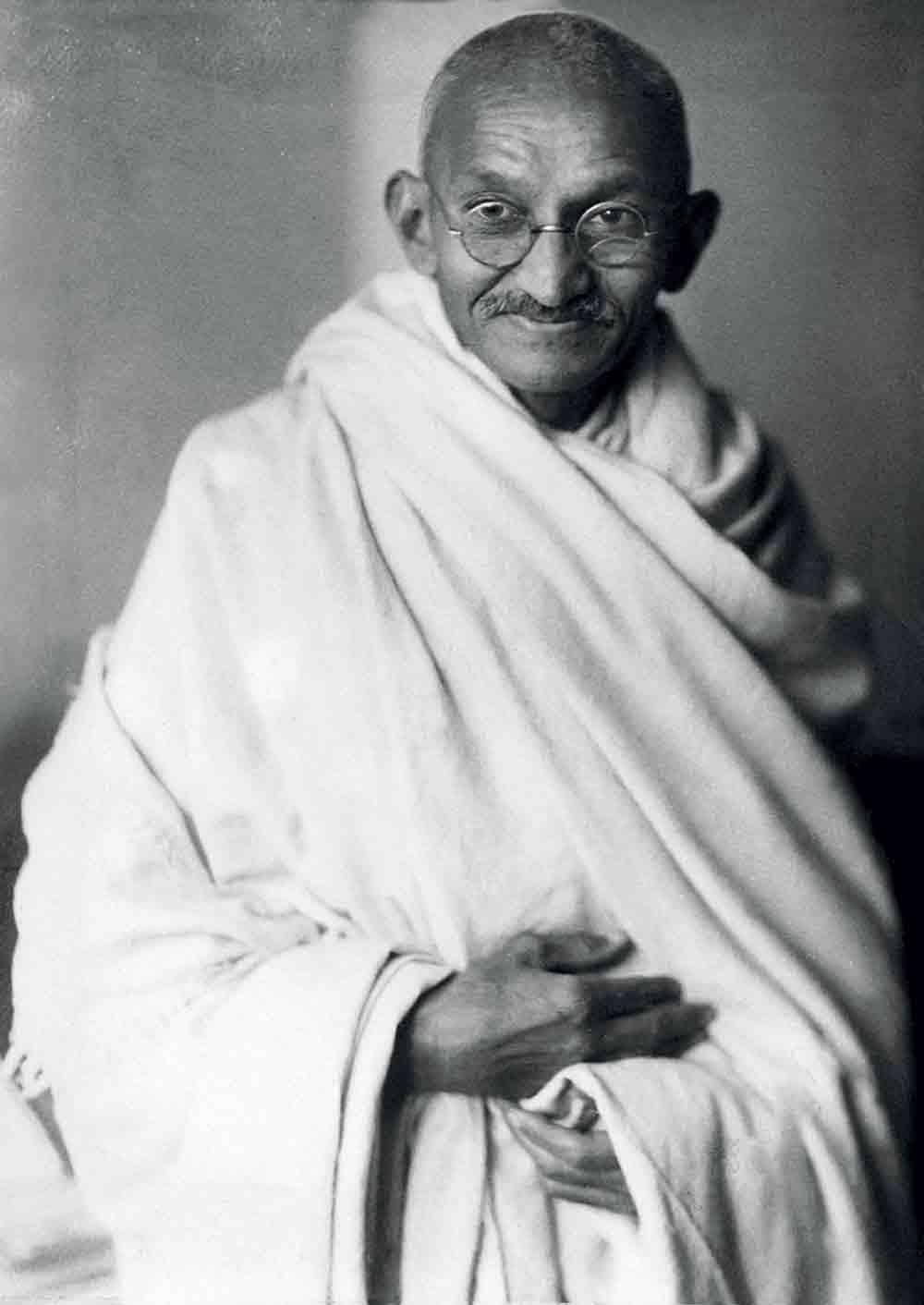

In the story of human progress, some figures emerge whose ideas transcend borders, languages and centuries. Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. were two such figures. The former faced colonialism in India, while the latter confronted racial segregation in the United States. Rather like characters from Jeffrey Archer’s Kane & Abel, Gandhi and King lived in different worlds and faced different forms of oppression. They never had the opportunity to meet each other either. Yet, their struggles were bound together by a single moral thread: the conviction that lasting change can be achieved through non-violent resistance. This shared belief shaped not only their respective nations, but also the very language of modern social movements.

Gandhi’s transformation began not in India but in colonial South Africa. Arriving in 1893 as a young lawyer, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi encountered the indignities of racial discrimination first-hand. The Pietermaritzburg incident was his “moment of truth”, where Gandhi was thrown off a train on his way to Pretoria, despite holding a valid first-class ticket.

Rather than retreat, he chose to act. He organised South Africa’s Indian community into the Natal Indian Congress, launched campaigns for basic civil rights, and eventually developed satyagraha, a philosophy of nonviolent resistance that involved confronting injustice with nonviolence and self-suffering to appeal to the oppressor's conscience and bring about social and political change.

For Gandhi, non-violence was not passive submission. It was a conscious strategy that sought to awaken moral conscience through peaceful resistance. “There are many causes that I am prepared to die for,” he once declared, “but no causes that I am prepared to kill for”. His campaigns mobilised thousands of ordinary people, many of whom were jailed, flogged, or shot for their defiance. Yet by refusing to mirror violence with violence, Gandhi unsettled the colonial establishment and exposed the injustice of its rule. By the time he left South Africa, conditions for Indians had significantly improved, and his philosophy was beginning to attract international attention.

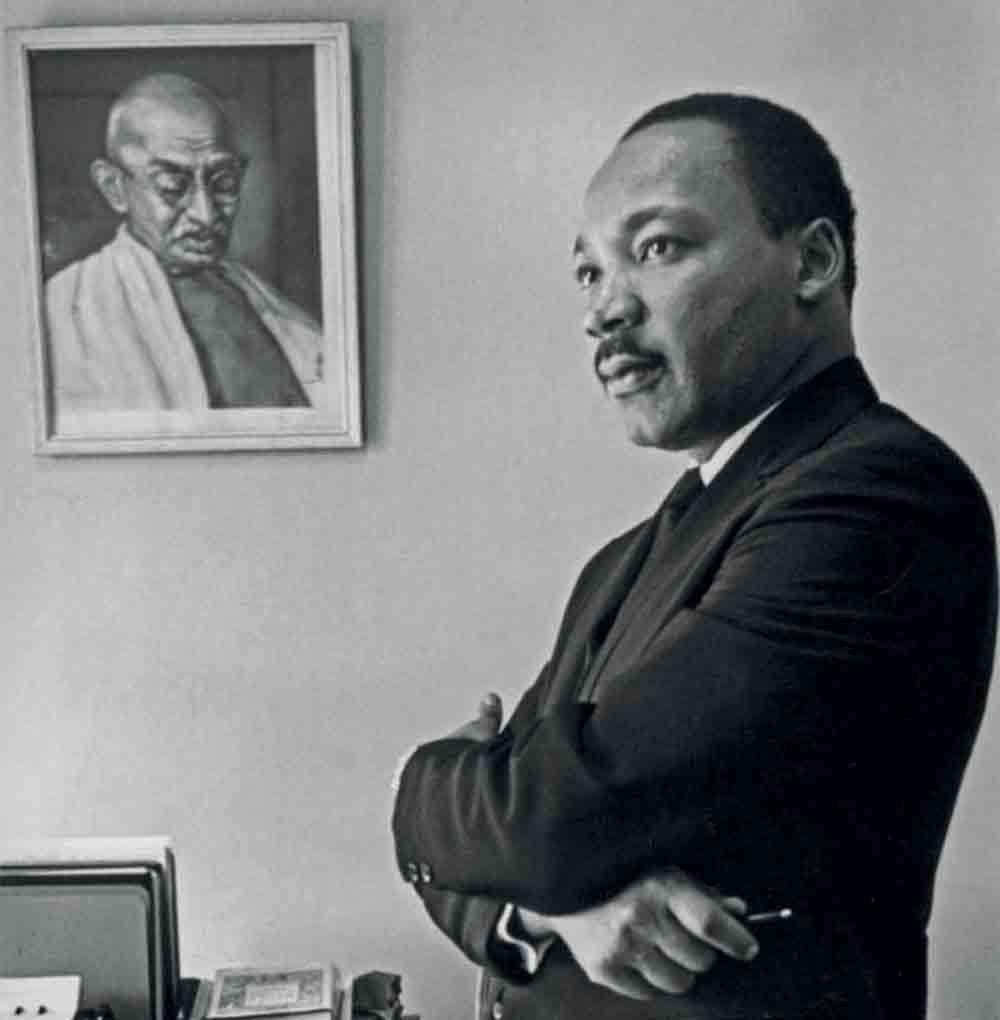

On the other side of the Atlantic, Martin Luther King Jr. would later discover Gandhi’s methods and find in them a blueprint for his own struggle. Born in 1929 in segregated Georgia, King grew up witnessing the daily humiliations of Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the American South from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. His intellectual journey led him to Gandhi’s writings during his theological studies, and in 1959 he travelled to India to deepen his understanding of non-violent resistance. He described the trip as “a pilgrimage to the land of Gandhi”, acknowledging that the Indian leader’s approach offered “the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity”.

King’s first major test came in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, when Rosa Parks’s quiet act of defiance against bus segregation sparked a city-wide boycott. For over a year, thousands of Black residents walked, carpooled and endured intimidation, while King emerged as the movement’s young, eloquent leader. The boycott succeeded, and Montgomery’s buses were desegregated by Supreme Court order, a victory achieved without a single act of violence. King would go on to lead campaigns across the American South, from Birmingham to Selma, consistently maintaining that non-violence was both a moral imperative and a strategic necessity.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”, he wrote in his Letter from Birmingham Jail in 1963, responding to critics who urged patience. His leadership came at great personal cost: arrests, bombings, constant death threats. Yet he refused to abandon the principle of nonviolence. His capacity to channel moral outrage into disciplined action was perhaps most visible during the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his iconic I Have a Dream speech before hundreds of thousands. “I have a dream,” he proclaimed, “that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character”. The words resonated far beyond America’s shores, becoming a universal statement of hope.

The parallels between Gandhi and King are striking. Both drew strength from spiritual conviction: Gandhi from Hindu, Christian and Muslim teachings; King from his Christian faith, and translated these into political movements grounded in moral authority. Both mobilised ordinary citizens rather than relying on elite power structures. And both demonstrated that nonviolence, far from being passive, can be an active, forceful agent of change when it is disciplined, strategic and rooted in principle.

Educationally, their lives offer profound lessons. Leadership, in their example, was neither about personal power nor charisma alone; it was about articulating a moral vision and sustaining it through collective action. Both understood the necessity of educating their followers. Gandhi trained volunteers in the discipline of satyagraha. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference held workshops to prepare activists to face violence without retaliation.

They showed that non-violent resistance requires intellectual rigour and emotional resilience.

Moreover, their ideas remind us that moral leadership is not confined by geography. Gandhi’s philosophy, forged in South Africa and India, crossed continents to shape the American civil rights movement. King, in turn, became a global symbol of justice, inspiring movements from anti-apartheid campaigns to contemporary struggles for equality. Neither man relied on the sword. Rather, both wielded the power of conscience.

For today’s students, these stories are not distant relics of history. They are living examples of how ideas can transform societies when carried by individuals willing to lead with integrity. Studying Gandhi and King is not simply an exercise in remembering famous names. It is about understanding the mechanics of social change - how ethical principles, strategic action and human courage intersect to reshape the world.

Both men paid the ultimate price. Gandhi was assassinated in 1948 at the age of 78; King in 1968 at just 39. Their deaths shocked the world but did not silence their message. Their philosophies continue to inform movements that seek justice without hatred, and resistance without vengeance. They stand as reminders that non-violence, when rooted in truth and discipline, can be one of the most transformative forces in history.

Their journeys also set the stage for another towering figure, Nelson Mandela, who, though he never met either Gandhi or King, would draw on their legacies to confront one of the most entrenched systems of racial oppression the world has known. His story, and the way it intertwines with theirs, forms the second part of this exploration into moral leadership across continents.

Read next Wednesday’s edition of The Sun for ECHOES OF CONSCIENCE, PART II.