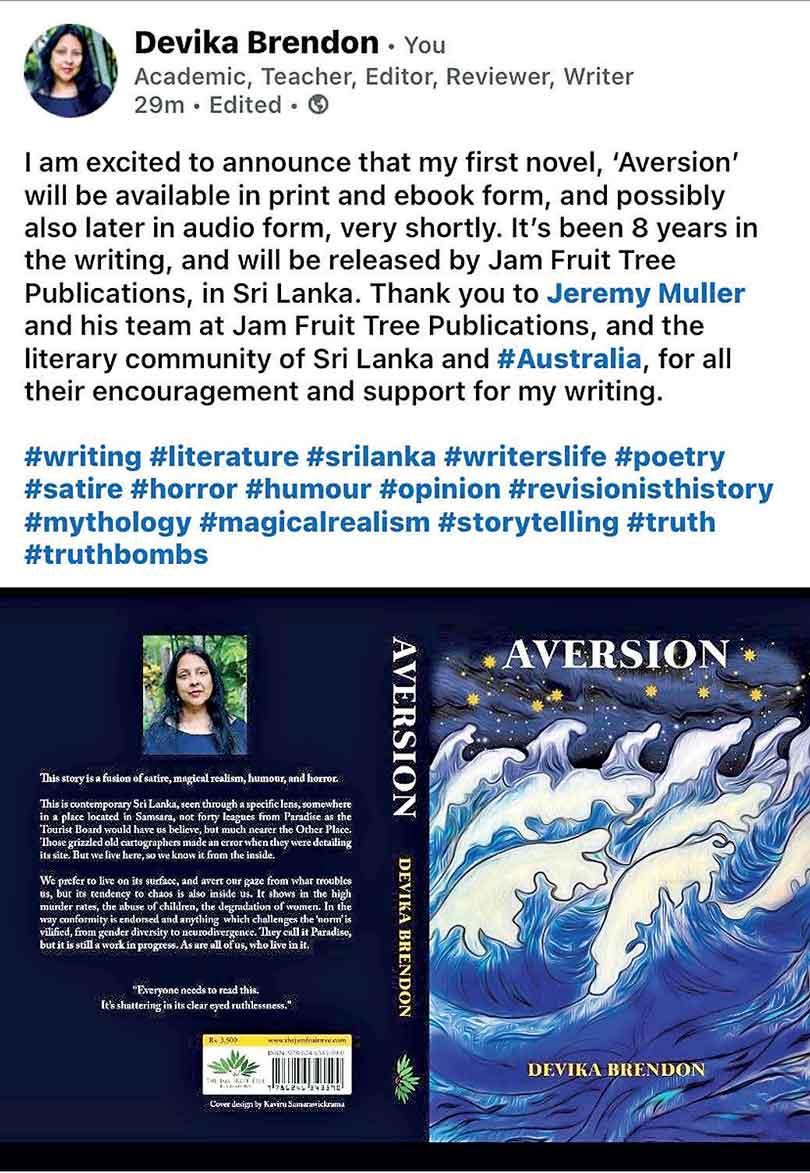

Devika Brendon’s Aversion is a fearless literary debut that defies genre and convention. A longtime academic, teacher and editor of English Literature, Brendon steps into fiction with the same sharp empathy and intellectual rigor that have long defined her work. Blending satire, magical realism, poetry, journalism and diary, Aversion follows a disillusioned investigative journalist navigating a fractured Sri Lanka, one far removed from the postcard paradise often portrayed abroad. With each fragmented chapter, Brendon’s protagonist confronts both public disorder and private turmoil, slowly moving from cynicism to clarity. The novel’s nonlinear structure mirrors the disjointed nature of life in a nation caught between collapse and hope. Aversion is more than a critique. It is a reckoning, a meditation on survival, and ultimately, a plea for empathy. In this conversation, Brendon opens up about her writing process, inspirations, and how fiction can challenge complacency and illuminate truth.

Q “Aversion” began as a series of outbursts. How did those raw expressions evolve into a structured narrative?

Each of the 26 chapters centres on an incident or issue, whether in the news, in public or in a personal setting. The protagonist, an investigative reporter, experiences frustration or bewilderment as she observes these moments. Her role demands constant observation and reporting, but the people she encounters, including social workers, activists and citizens committed to change, gradually challenge her initial aversion. The narrative began to take shape when these secondary characters started having real conversations with her. The book became what is known as a récit, a narrative built from recollection and anecdote. As the story progresses, the protagonist also begins to write poetry and explore her thoughts in more fluid ways. The structure is discontinuous, designed to reflect how life feels in contemporary Sri Lanka, chaotic, intense and fragmented. Drafting added polish, but I wanted to preserve the rawness because sometimes the gloss can obscure the truth.

Q You draw on Dante, Buddhist and Hindu mythologies, and even Carl Muller’s work. What connects these diverse influences?

The common thread is the journey, each individual navigating their own path through complexity. The title Aversion touches on a key source of suffering, our instinct to avoid pain and uncomfortable truths. In Sri Lanka, as elsewhere, people often mask reality with smooth surfaces. But I wanted to explore what lies beneath, what we don’t say, don’t face or can’t bear. We are interconnected. Our actions and inactions affect others. The book’s sharpest satire targets those who act not just with ignorance but with deliberate callousness. There’s a quote I love: “God lives in the way you don’t look away.” It resonates deeply. It is hard to stay engaged with suffering and cruelty because we are all exhausted. But the best people I know stay connected. They try. That spirit fuels the novel’s

moral spine.

Q You weave together fiction, journalism, poetry and diary. What were the freedoms and the challenges of this hybrid form?

It is definitely a medley. Writing in this form felt like a liberation. It allowed me to portray a protagonist whose growth unfolds in many tones, serious, tender, chaotic, witty. But yes, it might challenge readers expecting a conventional single-tone novel. Aversion is more mosaic than monolith. It is made of coloured fragments, and you need imagination and awareness to piece them together. The hybrid form mirrors real life. We don’t live in one genre. We oscillate between roles, professional, personal, poetic, political.

Q How do you balance introspection with outward engagement, both in your writing and your daily life?

It is always a struggle, but a necessary one. Extremes don’t help. We must find a rhythm between private reflection and public action. I try to pace myself, to maintain checks and balances. Mindful action is ideal, though spontaneity gives us life. You have to come out of your shell. One doesn’t want to remain a beautiful dreamer forever. Progress, both personal and collective, requires real-world engagement. In that sense, Aversion is also a record of learning to balance these aspects.

Q Your next books include historical fiction, romance, thrillers and even a children’s series. What drives this genre fluidity?

I am an explorer by nature. I grew up reading across genres with enormous pleasure. Now I want to try expressing my own stories in those fields. The next book is historical fiction, set in King Lear’s Britain, and draws on trauma recovery and interpersonal dynamics. Another is set in the Australia where I grew up. Then there is a love story that travels between Ireland and Iceland, its heroine is named Lara, because her parents loved Dr. Zhivago. I am also working on a satirical thriller set in London’s ruthless property market and adapting a children’s story I wrote years ago into a series. Until now, I have mainly written short stories and poetry. Now I am deeply interested in character development. I want to create people who feel alive, not just like caricatures. The joy is in watching them evolve, how they speak, what they wear, what they will

do next.

Q You’ve mentioned the difference between writing short stories and novels. Could you expand on that?

Short stories are like condensed crystals. Every word carries weight. Novels are different. They offer a larger canvas. You have space to let characters unfold and let the story breathe. In a novel, you can explore inner change over time. That’s what fascinated me in Aversion, watching the protagonist move from anger to awareness. The pace and process of change became central to the story.

Q What has the audience response been like? Have reactions surprised you?

The responses have been deeply moving. Many readers have told me the book jolted them in a good way.

Some highlights:

“Full of dark humor… a wake-up call

to everyone lulled by the island breeze.”

“It slapped me a few times because

I saw myself in it and that’s what good

writing does.”

“It invites confrontation, ‘come at me, bro’ energy, and that’s kind of badass.”

“A very honest portrayal of the dark core of SL beyond the gloss and shine shared

on SM.”

These reactions reassure me that the novel’s confrontation with truth, however messy or uncomfortable, resonates.

Q Finally, what do you hope Aversion leaves readers with?

I hope it leaves readers with compassion, with courage and with a willingness to look more deeply at the world, at others and at themselves. Aversion does not pretend to have neat solutions. But it insists on presence, on engagement and on being awake. That is the first step toward healing. And maybe even joy.

Aversion is more than a novel. It is an artistic reckoning. In blending truth with fiction, satire with sincerity, Devika Brendon has created a work that dares readers to see beyond illusion and inertia. It asks difficult questions and offers no easy answers. But in doing so, it illuminates something essential, the power of attention, of honesty and of narrative itself.