To rethink the origins of the Sinhala people is not to reject heritage, but to release it from the confines of a single story.

Sinhala identity is not the gift of a prince. It is a palimpsest, a script rewritten over time, layered with pain, pride, fusion, and forgetting.

1

The Origins We Inherited

Most Sri Lankans learn, early and unquestioningly, that their genesis begins with a prince: Vijaya, exiled from India, arriving on island shores around 500 BCE. Accompanied by 700 men, he tames the land, marries a local princess, and becomes the fountainhead of the Sinhala people. This myth, immortalised in the 5th-century Mahāvaṃsa, is retold with the cadence of gospel. It offers kings a pedigree, the island a first sovereign, and a people their origin.

But what if Vijaya was never meant to be taken literally?

Modern scholarship, from archaeology to genetics to critical historiography, invites us to rethink the question of Sinhala origins not as a point, but as a process. The idea that Sinhala identity emerged suddenly, fully-formed from a single migrant leader and his retinue, has little basis in material or historical evidence. It is, in essence, a narrative of legitimacy, not one of ancestry.

2

The Function of the Vijaya Myth

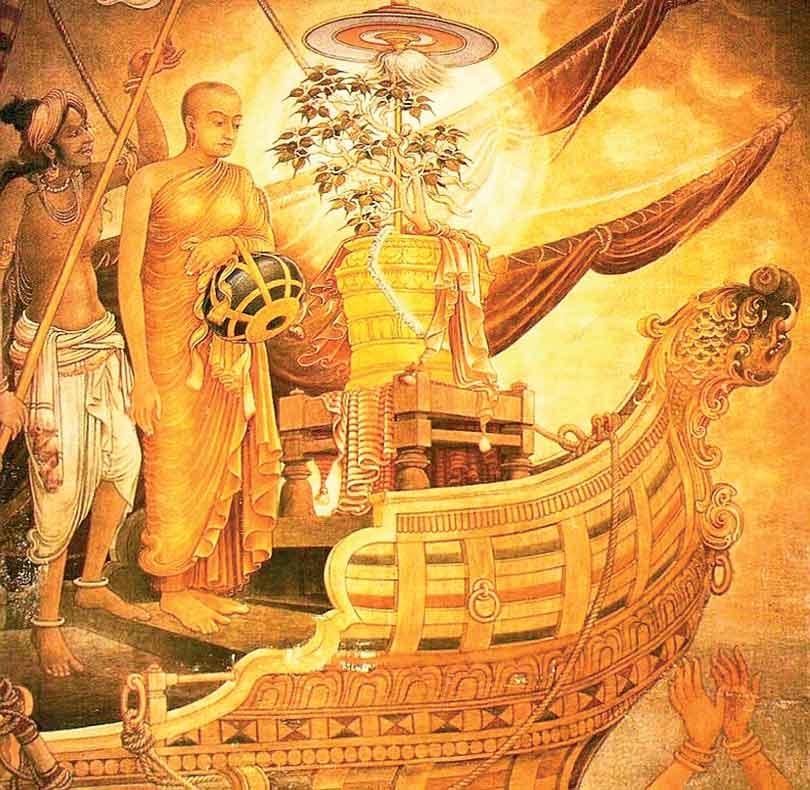

The Mahāvaṃsa, composed by Buddhist monks in the 5th century CE, was never intended as neutral history. It was political theology; a chronicle written to link the island’s kingship to the Buddha’s mission. Vijaya’s arrival occurs not incidentally, but on the very day of the Buddha’s death. This synchronicity is deliberate: it casts Sri Lanka as a chosen land, its first ruler divinely aligned with the Dhamma’s unfolding.

As historian S. Pathmanathan has notes that Vijaya’s genealogy functions not to explain population origins, but to explain political sovereignty. In the context of South Asia, where lineage and dharmic alignment mattered deeply to royal legitimacy, such myths were essential tools of rule. That the Vijaya story centres on exile and conquest, a rogue prince, a defeated indigenous woman (Kuveni), a civilising mission, should also alert us to its ideological underpinnings. It reproduces Brahmanical tropes of order over chaos, foreign over native, male over female.

3

The Archaeological and Genetic Record

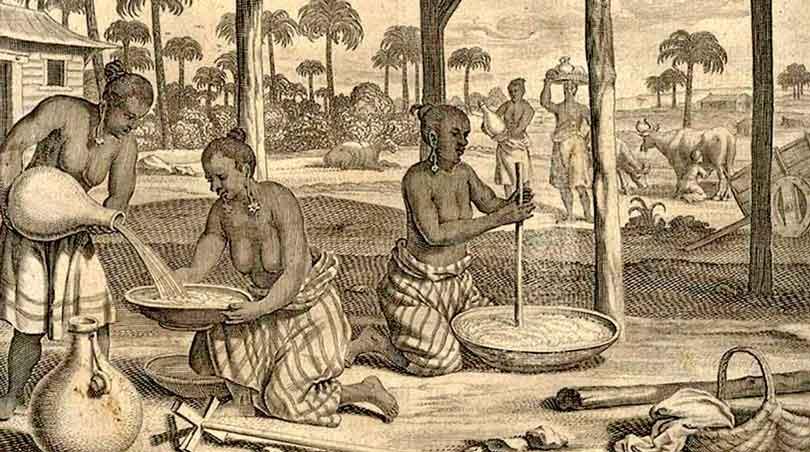

Archaeology tells a more fragmented, but also more plausible, story. Human habitation in Sri Lanka stretches back over 38,000 years. The Balangoda culture, known for its microlithic tools and cave dwellings, long predates any Indo-Aryan arrival. Even the famed Anuradhapura civilisation, often tied to the Sinhalese “start,” shows cultural continuities with pre-Vijayan layers, including megalithic burial practices found across South India and Sri Lanka alike.

Moreover, genetic studies complicate the purity of the myth. A 2014 global admixture study by Hellenthal et al., published in Nature, found that the Sinhalese genetic profile is shaped by multiple waves of ancestry, North Indian, South Indian, and some minor Southeast Asian inputs, spread over centuries. There is no evidence of a single founder group. As geneticist G. Perera concluded in a 2011 Sri Lankan study, the population reflects millennia of interaction, not a singular point of origin. In short, the Sinhala people are not born of a prince’s ship. They are born of centuries of migration, marriage, and cultural entanglement.

4

The Veddha Question

A second misconception often trails the Vijaya story: that the Veddhas [Sri Lanka’s indigenous forest-dwelling community] are either the “original Sinhalese” or the pure antithesis of them. Both claims are false.

Ethnographic and genetic work by Seligmann (1911) and more recent anthropologists like Susantha Goonatilake have shown that the Veddhas, far from being a static or “primitive” group, are deeply hybridised, having intermarried with low-country Sinhalese, Tamil, and even Moor communities over generations. Their rituals, kinship structures, and dialects reveal layers of assimilation and distinction, not isolation.

Moreover, the figure of Kuveni, the demon-queen seduced and discarded by Vijaya, is frequently read as the proto-Veddha woman. Yet this too is more literary than ethnographic. Kuveni’s demonisation mirrors South Asian tropes of wilderness and female unruliness—not a faithful depiction of a real ethnic other.

To elevate the Veddhas as the “true” origin of Sinhalese, or to cast them as wholly separate, is to fall into modern identity traps built on 19th-century ethnoracial thinking.

5

Language as Evidence of Exchange

Linguistics, too, tells a story of mixture. Sinhala is an Indo-Aryan language, descended from a Middle Indic Prakrit likely brought over by early merchants, monks, or migrants from the subcontinent. But its structure is heavily Dravidianised, its syntax, vocabulary, and phonology show deep contact with Tamil and other South Indian tongues.

The work of Wilhelm Geiger and later James Gair reveals that Sinhala developed not in splendid isolation but through sustained bilingual communities, particularly in the dry zone and maritime fringes. What we call “Sinhala” today is not a frozen vessel of Vijaya’s tongue, but a creolised language of encounter.

6

The Sinhala Identity as a Political Evolution

If the Sinhalese did not begin with Vijaya, then when did they begin?

The answer lies not in a date, but in a gradual process of ethnogenesis, a term used by scholars to describe the formation of group identity over time, often through the consolidation of religion, language, and political narrative.

From the Anuradhapura period through to Polonnaruwa, Sinhala identity took shape as a Buddhist identity, bound to royal ritual, language standardisation, and monastic chronicling. It was continually reshaped by war, migration, colonial contact, and ritual performance.

To be Sinhala was to belong to a kingdom where Buddhism was sovereign, Pāli was sacred, and kingship was encoded in cosmo-political order. It was never reducible to one myth, one bloodline, or one people.

7

Conclusion: A People of Many Beginnings

To rethink the origins of the Sinhala people is not to reject heritage, but to release it from the confines of a single story.

Vijaya may have given the chronicles their founding act, but the real beginnings are richer, and far more complex. They lie in the migrations that never made it to manuscript and the languages spoken in the shadow of shrines.

Sinhala identity is not the gift of a prince. It is a palimpsest, a script rewritten over time, layered with pain, pride, fusion, and forgetting. And perhaps, in that complexity, lies its true dignity.