This article forms the second part of our three-part exploration of the Ramayana’s Lankan dimensions. Last week we examined Ravana, whose image oscillates between historical conjecture and epic villainy. This week, we turn to Sita, whose sojourn in Lanka is among the most contested episodes in the entire tradition. Unlike Ravana, whose role was flamboyant and martial, Sita emerges as a paradox: powerless in circumstance, yet central to the epic’s moral and political stakes. To understand her presence in Lanka, we must move beyond devotional readings and examine the layers of text, folklore, and archaeology that have shaped her image.

The Abduction in Textual Tradition

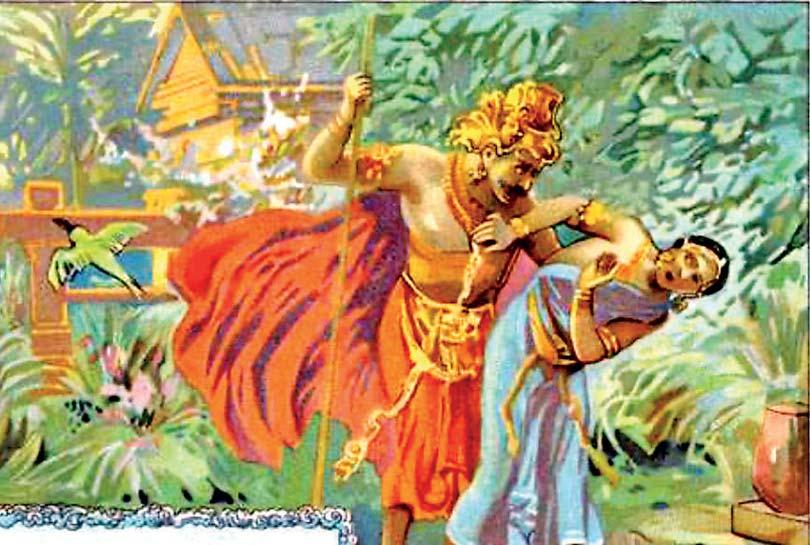

In Valmiki’s Sanskrit Ramayana, Sita’s abduction is a pivotal event. Ravana, disguised as a mendicant, lures Rama and Lakshmana away and carries Sita across the sea. Within the Ashokavana, she resists his advances and insists on fidelity to Rama. Sheldon Pollock (1986) notes that Sita here becomes “the embodied site of dharmic anxiety,” her chastity symbolizing the fragility of cosmic order. Yet regional versions complicate this picture. In Kampan’s Tamil Iramavataram (12th century), Sita’s resistance is described with richer emotional vocabulary, where her devotion becomes an act of bhakti in itself. Jain Ramayanas offer even sharper divergences: according to the Paumacariya of Vimalasuri (c. 3rd–5th century CE), Ravana never abducts Sita at all. Instead, a demoness substitutes a double (a maya-Sita), thereby protecting her virtue. Scholars such as Paula Richman (1991) and A. K. Ramanujan (1991) stress that these variations are not peripheral but central to how communities across South and Southeast Asia have interpreted Sita’s role. The Lanka episode is not one story but many, each inflected by local politics, theology, and gender norms.

Lanka as a Landscape of Captivity

Sita’s Lanka is imagined not as the bustling capital of Ravana but as a confined garden. Archaeological associations have been drawn to Sita Eliya in Nuwara Eliya, where local tradition identifies a grove as her site of captivity. John Holt (1996), in his work The Religious World of Kandy, notes how modern Sri Lankan Hindu communities have sacralized such sites, blending epic memory with living pilgrimage. The confinement of Sita has symbolic resonance. Stephanie Jamison (1996) highlights how gardens in Sanskrit epic often stand for controlled fertility, women’s sexuality enclosed and policed. In Lanka, Sita’s enclosure amplifies this motif, presenting her as both vulnerable and resistant.

Trial by Fire: Politics of Purity

Even after Ravana’s defeat, Sita must undergo an agnipariksha (ordeal by fire). Scholars have long debated this episode. Wendy Doniger (1999) interprets it as the dramatization of patriarchal suspicion, where female fidelity must be verified through supernatural trial. Uma Chakravarti (1990) situates it in the broader South Asian discourse on stridharma, noting how Sita’s trial underscores the patriarchal bargain: a woman’s chastity underwrites dynastic legitimacy.

This episode resonates powerfully in Lanka’s own memory of Sita. The fire trial occurs not in India but, according to several traditions, still on Lankan soil. Thus, Sita’s body becomes the stage where Lanka itself plays its final role in the Ramayana. In last week’s discussion of Ravana, we saw how he embodied the ambition and downfall of kingship. Sita, by contrast, represents endurance and restraint. Yet both figures converge in Lanka: Ravana’s desire defines Sita’s resistance, while Sita’s refusal seals Ravana’s fate. To read one without the other is to miss how the Ramayana makes Lanka both throne room and prison, battlefield and garden.

Historiography and Memory

Scholars such as Romila Thapar (Cultural Pasts, 2000) remind us that the Ramayana cannot be read as a singular narrative of history. Its multiplicity reflects centuries of social negotiation. In Lanka itself, the story of Sita has functioned as a bridge between Tamil Hindu communities, Buddhist retellings, and even colonial accounts fascinated by epic geography. Thus, Sita’s presence in Lanka is not only mythological but historiographical. It reveals how memory, gender, and landscape intertwine to create a layered archive, where myth bleeds into sacred geography, and where Lanka becomes inseparable from Sita’s suffering and survival.

Sita in the Classical Canon

In the Valmiki Ramayana, Sita is cast as the archetype of chastity and devotion. Abducted by Ravana and held captive in Lanka, she resists his advances with unwavering fidelity to Rama. Her ordeal culminates in the trial by fire, where her purity is tested before she is reinstated as Rama’s wife. This canonical portrayal has long dominated South Asian imaginaries, where Sita embodies pativrata dharma, the ideal of the devoted wife. But to take only Valmiki’s version as truth is to silence a vast landscape of alternative tellings, where Sita’s story is not of passive endurance but of agency, estrangement, and sometimes even refuge in the hands of Ravana himself.

When Sita Leaves Rama: Alternative Traditions

In Jain Ramayanas, especially the Paumacariya of Vimalasuri (c. 3rd–5th century CE), Sita’s abduction never occurs. Instead, through narrative innovations like the maya-Sita (illusory double), the real Sita is protected, while the confrontation between Rama and Ravana unfolds on other terms (Richman, 1991). In some strands of this tradition, Sita’s separation from Rama arises not from Ravana’s violence but from Rama’s own failure as a husband. In Tamil folk ballads and songs, collected by ethnographers in the 20th century, Sita sometimes runs from Rama himself. Faced with his suspicion and severity, she seeks shelter elsewhere. In several versions, it is Ravana who offers her sanctuary. Here, the Lankan king ceases to be a predator and becomes a protector; an inversion that profoundly unsettles the moral binaries of the canonical epic (Ramanujan, Three Hundred Ramayanas, 1991). In Sri Lankan folk traditions, particularly in narratives that valorize Ravana as a national ancestor, Sita’s presence in Lanka is imagined not as captivity but as hospitality. Anthropologist Rohan Bastin (2002) records how Sinhala communities re-read the Ramayana to emphasize Ravana’s kingship, where Sita’s time in Lanka reflects refuge, not abduction.

Sita, Agency, and the Patriarchal Archive

Modern feminist scholars have argued that the silences in Valmiki’s Ramayana, particularly around Sita’s voice, are precisely what allowed such divergent traditions to flourish. Nabaneeta Dev Sen (1992) notes that women’s Ramayanas, transmitted orally in regional languages, often gave Sita agency denied to her in the Sanskrit canon. Uma Chakravarti (1990) points out that the trial by fire is not a test of Ravana’s defeat but of patriarchal control over women’s bodies. In these alternative Sitas, then, we see an active rejection of Rama’s harshness, a refusal to be merely tested, and in some cases, the choice of Ravana as refuge. What emerges across these variations is not a single Sita but a spectrum. In one telling, she is the perfect wife, enduring humiliation in the name of virtue. In another, she is a woman who chooses exile from her husband’s suspicion. In still others, she is a refugee, whose safety lies not in Ayodhya but in Lanka. The instability of Sita’s image reveals something larger about South Asian epic traditions: they are never singular, never fixed. Each re-telling reflects the values, anxieties, and resistances of the community that preserved it. To remember only the fire-trial is to flatten this plurality.

Conclusion: Between Captive and Queen

Sita in Lanka is a paradox. She is captive yet central, silent yet resonant, doubted yet revered. Her ordeal has been reimagined across centuries, each version refracting contemporary concerns. If Ravana in our last piece emerged as both villain and king, then Sita here emerges as both captive and fugitive, victim and agent, silenced woman and speaking subject. In the next article, we will turn to Rama himself, the third figure of this triad, and ask whether the “perfect king” has fared any better in history than in myth.