When the British East India Company set foot on Ceylonese soil in 1796, they did not just bring their muskets, their ships, and their laws. They brought with them a language that would, for over a century, become both a weapon of class and a badge of prestige: the King’s English. By the time the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission of 1833 laid the groundwork for the Ceylon Civil Service, fluency in English was not merely desirable; it was essential. If one wished to serve in the coveted Civil Service, modelled on Britain’s own, one had to master the tongue of the British Empire.

01)

WALTER SCOTT AT TEA: WHEN ENGLISH BECAME OURS

By the early 1900s, the English language was no longer considered a foreign tongue. It was the language of the courtroom, the classroom, and the cricket field. Ceylonese gentlemen read Walter Scott for leisure, young men from Colombo and Kandy dreamt of Oxford and

Cambridge, and Christian missionary schools like CMS Ladies’ College and Trinity College polished the spoken and written English of their students to near-native elegance. Individuals who once referred to “aiya” and “nangi” at home began to call their relatives “brother” and

“sister” instead. Lawyers and planters alike craved the status of being “gentlemen of the realm,” and the English language was the passport to that imagined aristocracy.

02)

A BROWN MAN AT THE UN: THE PEAK OF PROFICIENCY

Independence in 1948 did little to diminish the prestige of the English language. In fact, it remained the measure of refinement. Letters, irrespective of whether they were personal or official, were written in English, for neither the Sinhalese language nor the Tamil language were deemed sophisticated enough for polite society. When Finance Minister J. R. Jayewardene delivered his historic address at the United Nations at the Japanese Peace Treaty Conference in San Francisco in 1951, the world listened in awe at his eloquence. Here was a brown man from a newly independent island, speaking with the authority, rhythm, and cadence of an Oxonian scholar (which he had not attended, mind you!). The English language had not just taken root; it had blossomed.

03)

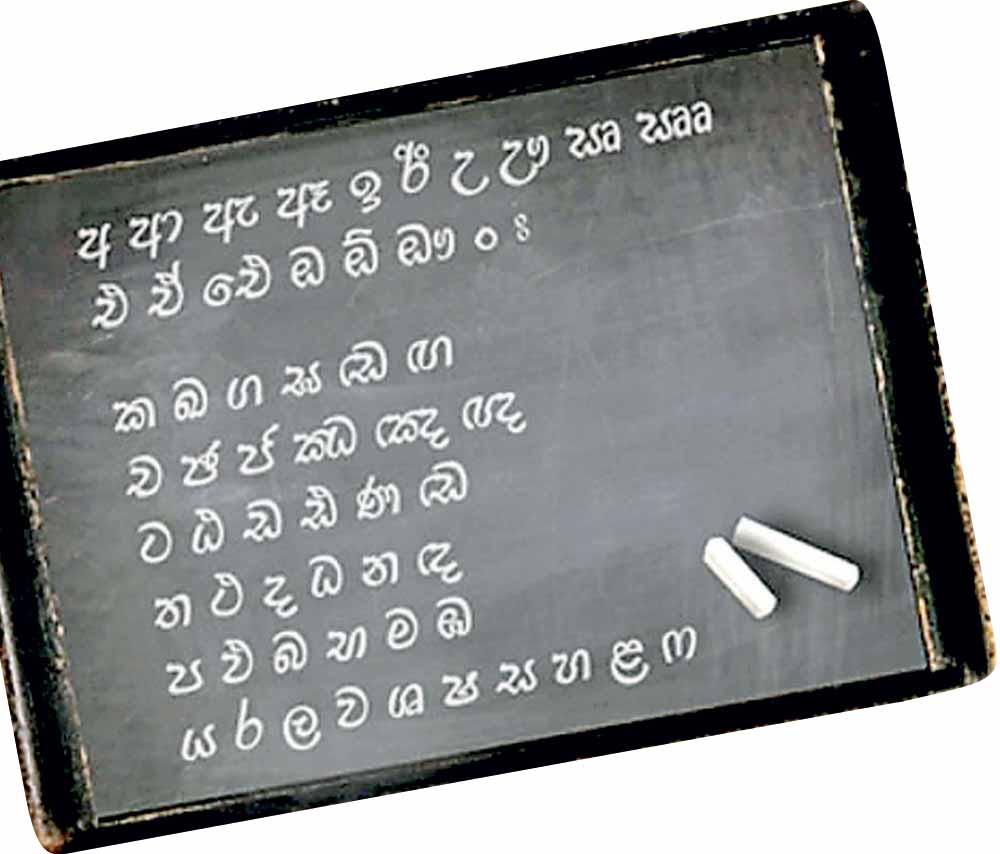

THE DAY THE CLASSROOM CHANGED

But then came the unravelling. In 1942, under Dr. C. W. W. Kannangara’s free education reforms, the medium of instruction in government schools shifted from the English language to the Sinhala and Tamil languages. The intent was noble: to democratise education, to give every child access to knowledge in their mother tongue. Yet the unintended consequence was a slow estrangement from the English language, and by 1956, with Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike’s Official Language Act (aka the Sinhala Only Act), English was no longer the unifying thread it had once been. What was once a symbol of opportunity became a marker of elitism, and gradually, a casualty of politics.

04)

FROM BAILA TO “SHAPE”: ENTER SINGLISH

Still, there were holdouts. Families, schools, and individuals clung to bilingualism, balancing fluency in both the English language and their native tongues. But by the 1980s and 1990s, another change was brewing. English began to mutate. Desmond de Silva’s baila songs playfully wove Sinhala and English together with lyrics such as “I saw you kissing aayage kolla”. Slang words appeared in colloquial language. The word “shape” no longer meant form or outline; it meant “we can sort it out.” By the dawn of the new millennium, the hybridised tongue we now call “Singlish” was entrenched.

05)

2025: LOST IN TRANSLATION

Today, in 2025, we live in the aftermath of this linguistic collision. On the one hand, there is a certain pride that our “Sri Lankanisms” are now acknowledged beyond our shores, with words like “aiyo” and “pothering” making an appearance in the Oxford Dictionary. Yet on the other, we are left with a fractured, half-baked colloquialism that often leaves young people stranded between languages. They speak in a hybrid of Sinhala, Tamil and English, yet master none. Worse, when faced with life after college, be it at an interview, a corporate boardroom, or a foreign campus, our students shrink. The global economy still values the English language as the medium of commerce, science, and diplomacy. Yet too many of our local graduates, stumble when asked to present a report, too many shy away from conversations with foreign colleagues, and too many find themselves disqualified from opportunities, not for lack of intelligence, but for lack of articulation.

06)

FROM OXBRIDGE TO “HALF-BAKED”: WHERE DID IT ALL GO WRONG?

How did a nation that once produced Oxbridge graduates, articulate statesmen, and elegant letter-writers arrive at a point where students dread standing up to speak in English, but also hesitate to fall back on their mother tongue for fear of seeming “less educated”? The truth is, we killed the English language in Sri Lanka not with one stroke, but with a thousand small cuts. In chasing linguistic nationalism, we failed to preserve linguistic proficiency. In mocking “elites,” we failed to see that the English language was never the enemy but rather a tool for making a mark on the global playing field which could co-exist with both of our country’s mother tongues. And in allowing slang and half-English hybrids to dominate, we forgot that a language only grows when it is cultivated, not left to deteriorate in neglect.

07)

RESURRECTION OR RUIN?

Once, the mastery of English opened doors for Ceylonese men and women to walk confidently into courtrooms, universities, and global arenas. Today, our challenge is not to restore English as a colonial badge of honour, but to reclaim it as a living, breathing skill that empowers rather than excludes. English should not be the language of the elite; it should be the language of access. The murder of the English language in Sri Lanka has been a slow one. But perhaps it is not too late for resurrection. For if our young people can rediscover not just the grammar but the confidence, not just the vocabulary but the courage, then the English language in Sri Lanka may yet live again, not as the master’s tongue, but as the people’s tool.

And this responsibility falls squarely on today’s students. The ability to communicate in English is no longer a luxury; it is a necessity. It determines whether you can compete in the global marketplace, whether you can make your voice heard in international forums, and whether you can lead rather than simply follow. How then should you begin? Read widely - not to get through a mere exam, but for pleasure and, ideally, for mastery. Speak up in class, however hesitant you may feel. Practise public speaking, debate, or even casual conversation in English with friends. Write letters, essays, or even journal entries to strengthen the flow of thought in the language. Proficiency comes not through memorisation, but through practice, and the sooner our young people embrace this, the sooner the English of yesteryear may be revived - not as a murdered relic of a colonial past, but as a vital instrument for a confident future.