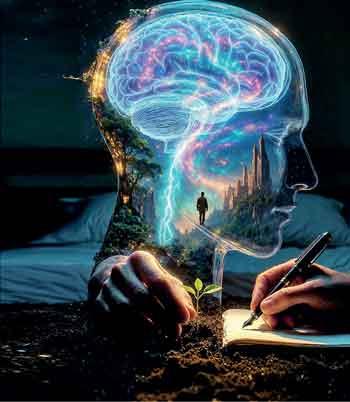

Maladaptive daydreaming has been a topic of interest to me for quite some time, not because it is trendy but because it silently affects far more people than most realize. It sits in that strange place between creativity and coping, somewhere between imagination and avoidance. For something so private and internal, it has surprisingly visible consequences in everyday life. Most people daydream, and that’s completely normal. It’s normal to drift mentally, replay conversations, imagine better outcomes or future scenarios, but maladaptive daydreaming isn’t just mental wandering. It’s becoming deeply absorbed in vivid, ongoing fantasy narratives to the point where real life begins to feel secondary. Time disappears, responsibilities get delayed, and the lines between fantasy and reality are blurred. Emotional energy gets heavily invested in imagined worlds rather than real-life experiences

Maladaptive daydreaming has been a topic of interest to me for quite some time, not because it is trendy but because it silently affects far more people than most realize. It sits in that strange place between creativity and coping, somewhere between imagination and avoidance. For something so private and internal, it has surprisingly visible consequences in everyday life. Most people daydream, and that’s completely normal. It’s normal to drift mentally, replay conversations, imagine better outcomes or future scenarios, but maladaptive daydreaming isn’t just mental wandering. It’s becoming deeply absorbed in vivid, ongoing fantasy narratives to the point where real life begins to feel secondary. Time disappears, responsibilities get delayed, and the lines between fantasy and reality are blurred. Emotional energy gets heavily invested in imagined worlds rather than real-life experiences

The term itself was introduced by psychologist Eli Somer in the early 2000s after he noticed trauma patients who described spending hours immersed in elaborate internal stories. Since then, online communities and research studies have shown that this experience is not rare. Many people report complex plots, recurring characters, and emotional attachment to their inner narratives. Even physical behaviours, like pacing, facial expressions, or listening to specific music, can intensify the experience. What makes maladaptive daydreaming different from normal imagination is not the creativity but the compulsive pull. People often want to stop or reduce it but feel unable to. It doesn’t feel like a harmless habit. It’s automatic, emotionally charged, and difficult to control, and because it happens entirely in the mind, it often goes unnoticed or misunderstood by others.

What’s Happening Psychologically

What’s Happening Psychologically

From a brain perspective, maladaptive daydreaming is linked to the default mode network, the system responsible for self-reflection, memory recall, imagination, and internal narrative building. This network naturally activates when we are resting or unfocused. In maladaptive daydreaming, however, it seems to become overactive, pulling attention inwards even when external focus is needed. Psychologically, the pattern often begins as protection. Many people who experience maladaptive daydreaming describe childhood events that were emotionally difficult; loneliness, high stress, or emotional neglect. For a child, imagination becomes a safe space, an escape. In fantasy, you can create control, belonging, admiration, and emotional fulfilment that may be missing in real life. Over time, the brain learns that fantasy provides quick emotional relief. Stress triggers daydreaming. Boredom triggers daydreaming. Emotional discomfort triggers daydreaming because the emotional payoff is immediate, and the habit is reinforced. Dopamine is released through excitement, emotional engagement, and narrative immersion, strengthening the urge to return to the inner world again and again.

There is also significant overlap with other psychological patterns. Research has found connections between maladaptive daydreaming and ADHD, anxiety disorders, depression, obsessive-compulsive traits, and dissociative tendencies. This helps explain why maladaptive daydreamers struggle with attention regulation, emotional avoidance, and repetitive mental behaviour. Another important factor is identity formation. Many people create idealized versions of themselves in fantasy; more confident, more desired, more successful, more understood. While this can feel empowering at first, it can slowly create dissatisfaction with real life. Reality begins to feel emotionally flat in comparison, not because real life lacks meaning but because the brain has become accustomed to constant emotional stimulation.

When Imagination

Turns Against You

Maladaptive daydreaming becomes a problem when it interferes with everyday functioning. This rarely happens suddenly. It builds gradually. Tasks are postponed. Sleep schedules start to shift. Academic work or focus declines. Relationships feel harder to maintain. Real conversations start to require more effort while imagined interactions feel effortless and emotionally rewarding. One of the most difficult parts is the emotional attachment. People don’t just imagine random scenes; they develop long-term storylines and emotional bonds with fictional characters. Letting go can feel like losing something meaningful, and this is why telling someone to “stop daydreaming” is unrealistic. For many, the fantasy world carries emotional safety, validation, and identity.

There is also the cycle of guilt and escape. After spending hours lost in a fantasy, people often feel frustrated with themselves. That negative emotion then pushes them back into daydreaming for comfort. Over time, this loop becomes deeply ingrained. Because maladaptive daydreaming is invisible, many people suffer quietly. They assume they are alone in the experience or that it’s something to be embarrassed about. This isolation makes it harder to seek help or even recognize the behaviour as a psychological pattern rather than a personal failure.

Learning to Stay

Present Again

Reducing maladaptive daydreaming does not mean eliminating imagination. The goal is balance, learning to engage creativity without losing touch with reality. Awareness is the first step. Many people daydream automatically without noticing triggers. Identifying patterns such as boredom, emotional stress, specific music, or pacing makes the behaviour more conscious and therefore more controllable. Therapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy can help address avoidance habits and emotional regulation. For those whose maladaptive daydreaming is rooted in early emotional trauma, trauma-informed therapy can be especially effective. The aim is not to suppress imagination but to develop healthier ways to cope with emotional discomfort. Grounding techniques are also useful. Focusing on physical sensations, breath, and the immediate environment helps retain attention toward the present moment.

This strengthens the ability to stay mentally “here” rather than automatically escaping inwards. Some people find it helpful to redirect imaginative energy into more structured creative outlets like writing, art, or storytelling. Instead of letting fantasy consume random hours, it becomes intentional and productive, externally expressed.

Perhaps the hardest adjustment is emotional. Real life is quieter than fantasy and does not offer constant stimulation or dramatic emotional highs. Learning to live with that quiet and to find meaning in slower, more grounded experiences takes time, but it also creates something that fantasy cannot provide; real connection, growth, and agency. Maladaptive daydreaming shows just how powerful the human mind is, revealing our ability to build entire emotional worlds from thought alone. The challenge is not to destroy that ability but rather to learn how to live with it without disappearing into it.