Alia and Nimmu

The lamps were lit one by one by the graduates themselves. There was no rush. No nervous fumbling. No one stepping in to guide their hands. Each flame caught slowly, deliberately, as if the act itself mattered as much as what it represented. In Sri Lanka, oil lamps are lit for beginnings that deserve to be remembered. Weddings. New ventures. Sacred thresholds. But this was not a beginning granted by tradition or circumstance. This was a beginning claimed.

This was their graduation. I had come expecting something modest. A small ceremony, perhaps, with polite applause and careful speeches. What I walked into instead felt closer to a homecoming. The graduation of the Emerge Centre for Reintegration carried the gravity of a university convocation and the tenderness of a family gathering. It was formal without being stiff, emotional without being indulgent. Most importantly, it belonged to the young women at its centre.

I had known Kaavya, Emerge’s Communications Lead, for several years. I had heard her speak often and passionately about the organization, about survivors, about justice. She always spoke with conviction, warmth, and belief. What she never quite prepared me for was what this work looks like when it reaches its most important moment. When it stops being policy, programming, or intention, and becomes a lived crossing from one life into another. The graduates entered together, but they did not look like a group shaped by institutional life. There was no uniformity in their energy. Each carried herself differently. Some walked in with quiet confidence. Others smiled broadly, as if daring themselves to enjoy the moment fully. What they shared was ease. A comfort that come from trust. It was immediately clear that this ceremony was not designed to impress an audience. It was designed to honour the people who had earned it.

The programme opened with a pooja dance performed by the graduates themselves. It was self-taught, learned through repetition, discipline, and long hours of practice that no one outside the staff had witnessed. Watching them, I could not help but think about what it means for a young woman whose body has been a site of harm to stand in front of others and move with control, intention, and pride. In Sri Lanka, child sexual abuse is both pervasive and largely unseen. Studies estimate that between 14% and 44% of young people experience sexual abuse during childhood, with girls disproportionately affected. Most survivors know their perpetrators, a reality that complicates disclosure and keeps abuse hidden within families and communities. The numbers are staggering. But numbers alone cannot capture what happens to a child who chooses to speak. For those who do, safety often comes at the cost of separation. Survivors are frequently placed in state-run shelters during legal proceedings that can last five to ten years. These years coincide with adolescence, a period meant for experimentation, connection, and self-discovery. Instead, many grow up within institutional walls, removed from family, school, and community, with limited opportunities to build life skills or imagine futures beyond survival.

This is the quiet crisis Emerge has been working within for twenty years.

Founded by Alia Whitney-Johnson after a tsunami relief trip to Sri Lanka, Emerge began with a simple but radical belief. When a young survivor is brave enough to come forward, she deserves more than protection. She deserves the tools, relationships, and confidence to reclaim her life. What began as a response to injustice has grown into a globally supported, locally led organization working directly with teenage girls and gender-diverse youth living in Sri Lanka’s state-run shelter system. Emerge operates through two sister organizations. Emerge Global in the United States provides fundraising and strategic oversight. Emerge Lanka Foundation, a registered NGO, implements all programming on the ground. With authorization from the Department of Probation and Child Care Services, Emerge works within state institutions, often meeting survivors at their most isolated moments. The most difficult moment comes at eighteen. At the legal threshold of adulthood, survivors age out of shelters and are released into a world they have been shielded from for years. Simple tasks become overwhelming. Using public transport. Opening a bank account. Navigating a grocery store. Without family support or community networks, many face housing insecurity, unemployment, and renewed vulnerability, all while continuing to process trauma.

Emerge’s Centre for Reintegration exists for this moment.

I understood this not through a brochure or presentation, but by standing in that graduation hall. Nine graduates stood before us. Nine young women who had arrived at Emerge carrying histories most people will never have to articulate out loud. They did not recount those histories. They did not need to. Instead, they spoke about the future.

- Paba wants to own her own car.

- Nara hopes to reconnect with a family she lost long ago.

- Nani sees herself opening a boutique salon shaped by her taste, her hands, and her sense of beauty.

- Mathi spoke quietly about working her way up to becoming an office manager.

- Daara dreams of becoming a multi-talented hairdresser.

- Shani plans to challenge gender norms by riding a trailer bike.

- Yali is determined to become a CID officer.

- Meena dreams of hiring out her own green tuk tuk.

- Joan hopes to become a patient, caring nurse.

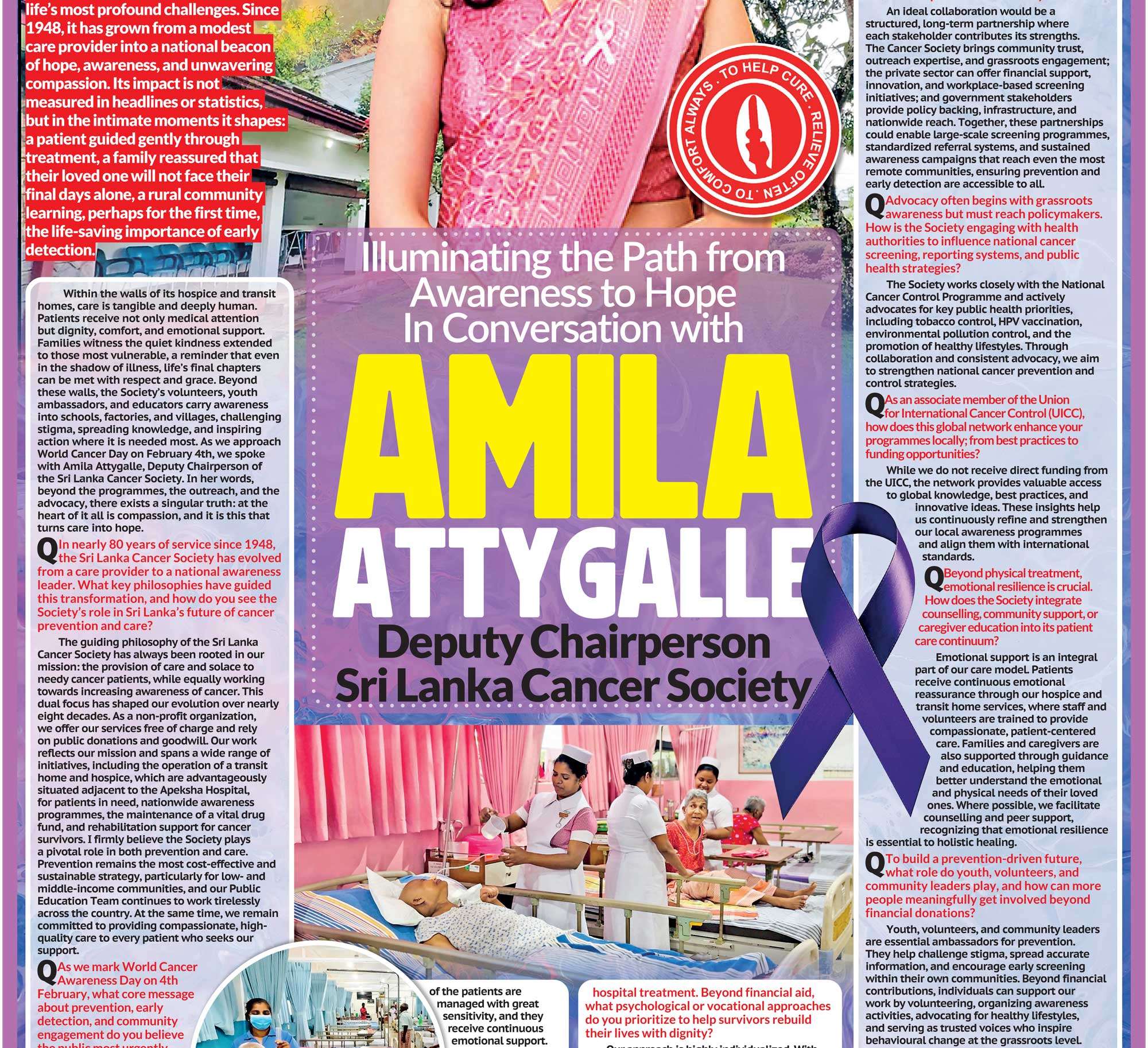

What struck me was not how ambitious they were, but how confidently they were held. For young women who had spent years being told where to be, when to sleep, when to eat, and how to live, the simple act of naming a future felt radical. The Guest of Honour was Nimmu Kumari. Her presence changed the room. A former care leaver herself, Nimmu was removed from her home as a child despite her mother’s opposition and spent more than fifteen years in institutional care. When she spoke about that time, she said only, “It was painful, but it was also the first time I felt safe.” That sentence lingered.

Today, Nimmu is a leading advocate for children’s rights, a global speaker, a co-founder of Asia’s first registered care leavers network, and the author of a memoir tracing her journey through abuse, institutionalization, and justice. But none of those titles mattered in that room. What mattered was that she had stood where these graduates were standing and had built a life forward. She spoke about what happens after care. About how freedom can feel overwhelming when you have been sheltered from the world for years. About learning to navigate money, transport, work, and relationships while still carrying unhealed wounds. Emerge steps in at that moment. The Centre is not a shelter. It is not a rescue programme. It is a place of transition. Survivors learn vocational skills, financial literacy, communication, and workplace readiness. Mental health support is woven into daily life. Just as importantly, they learn how to exist alongside others without fear.

One graduate spoke about the lotus during an extraordinary performance, “The Magnificent Lotus.” It is born in mud, she said, but it does not hide where it comes from. It allows the sun to pass through water and darkness, and it rises. “I am that lotus,” she said. “We are that lotus.”

Emerge often describes itself as a family of survivors and allies. Watching these young women that day, I understood that this was not metaphor. It was structure. It was consistency. It was staying. What was visible was dignity. As the ceremony ended, no one rushed to leave. Graduates lingered. Photos were taken slowly. Hugs lasted longer than usual. Many cried. There was no sense of closure, only continuation. Emerge had handed them back to society, but it had also given them something to return to.

In a country where child sexual abuse remains hidden and underreported, where survivors are silenced by stigma and fear, this work feels quietly radical because it refuses to abandon survivors once they speak. Watching the lamps burn low, I realized that what Emerge offers is not only opportunity, but permission. Permission to want. Permission to plan. Permission to belong. These young women were not being launched into the world that day. They were reclaiming it. And as they stepped forward, steady and unafraid, it was impossible not to believe that something irreversible had already taken place. They had emerged. Doriyaan Gunasekara, Programme Officer, described Emerge simply as, “hope, healing, and a chance to begin again.” Watching this graduation, it was hard to imagine a truer definition. Cheers Batch 12!

Online: www.emergelanka.org

Instagram: @emergeglobal