GenZing by Kiara Wijewardene

GenZing by Kiara Wijewardene

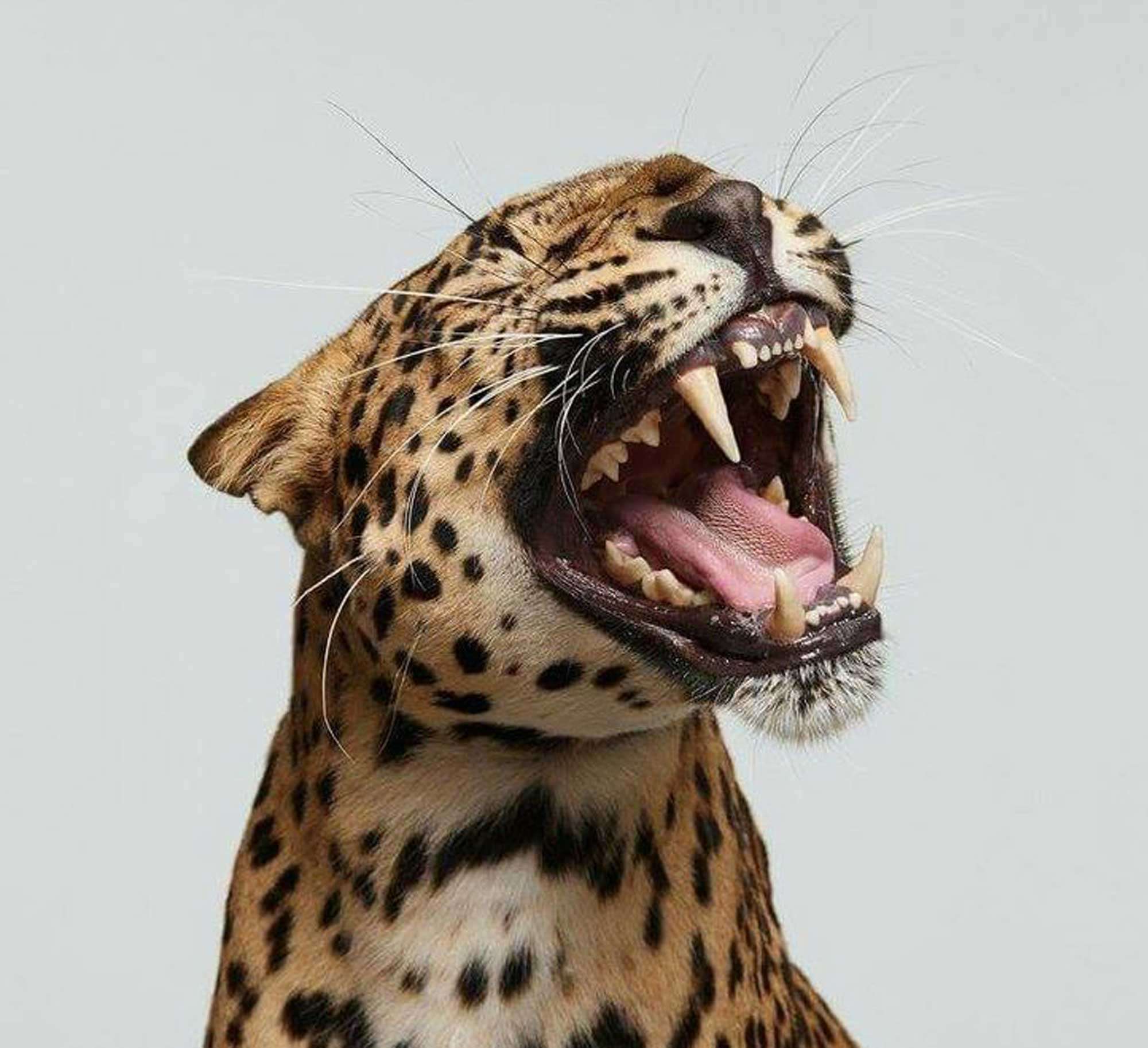

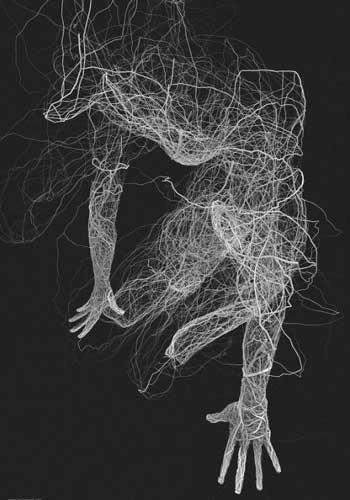

Risk has a strange pull. It is the reason someone drives too fast on an empty highway, experiments with substances, or stands at the edge of a cliff just to feel something. There is a thrill in pushing limits, a sensation that hits the body and mind in a way nothing else does. That sensation, the adrenaline rush, is both exhilarating and dangerous. Adrenaline, or epinephrine, is a hormone designed for survival. It prepares the body for immediate action, increasing heart rate, redirecting blood flow to the muscles, and sharpening attention. Historically, it enabled humans to escape predators or respond quickly to life threatening danger. Yet in modern life, threats are rarely literal. Still, some people actively seek situations that trigger that primal response. The question is not only why adrenaline feels powerful, but why we are drawn toward danger itself.

Why It Seems Appealing

Psychologists use the term “sensation seeking” to describe a personality trait characterized by the desire for novel and intense experiences. Individuals vary significantly in their need for stimulation. For some, ordinary life is engaging enough. For others, routine feels dull and even suffocating. High sensation seekers chase risk because it adds intensity to life. It transforms otherwise ordinary moments into ones charged with immediacy and focus. Neurologically, adrenaline rarely acts alone. Risk taking also triggers dopamine release, reinforcing behaviour by attaching pleasure to the act. When a dangerous choice ends safely, the brain links risk with reward. This loop helps explain why the first reckless decision is rarely the last. Optimism bias also plays a role. People tend to believe negative outcomes are more likely to happen to others than to themselves. Most individuals engaging in risky behaviours do not anticipate harm until it actually occurs. Risk can feel abstract, until it is not.

Control Is an Illusion

Risk taking can feel empowering. Choosing danger creates a sense of agency, a refusal to be constrained by caution, routine, or expectation. Heightened adrenaline compresses attention into the present moment, leaving little room for overthinking. For individuals who feel numb, overwhelmed, or constrained in daily life, this clarity can feel liberating. Yet the sense of control is often an illusion. Risk, by definition, involves uncertainty. External factors such as other drivers, chemical reactions, or physical limits cannot be fully managed. Heightened arousal can also impair judgment, prioritizing immediate reaction over long term planning. The same biology that evolved to save lives can, in modern contexts, create vulnerability.

Risk Escalates

Not all risk is harmful. Calculated risk is essential for growth. Pursuing new careers, performing publicly, or traveling alone involves uncertainty but expands capability without endangering survival. The problem arises when risk is pursued primarily for the chemical high. Over time, the same behaviour may no longer produce the original intensity. Baselines shift, and increasingly extreme actions are required to recreate the same sensations. Substance abuse, extreme sports, and reckless behaviour can follow this pattern. Social and cultural factors amplify this tendency. Risk is often glamorized. Speed is associated with confidence, recklessness with boldness. Media frequently highlights the thrill while minimizing the consequences. Injuries, addiction, and long-term harm are far less visible than the moment of excitement. For some, risk becomes identity. Being perceived as fearless or unpredictable can mask deeper motivations such as boredom, emotional distress, dissatisfaction, or the need for validation. Adrenaline becomes a distraction rather than an experience.

The Physical and Psychological Cost

The Physical and Psychological Cost

The body is not designed for chronic stress activation. Occasional adrenaline surges are adaptive, but repeated exposure can disrupt sleep, elevate blood pressure, and strain the heart. Psychologically, repeated cycles of intense arousal followed by emotional lows can create instability. Certain risks carry irreversible consequences. A split-second misjudgement on a highway, a substance misused, or a stunt executed without preparation can have lasting impact. The rush can feel convincing, producing heightened confidence and a reduced sense of vulnerability, but psychological arousal does not equal protection.

Rethinking the Need for the Rush

The desire for intensity is deeply human. Challenge and exhilaration can be meaningful. Problems arise when danger becomes the primary source of sensation. Understanding why we chase risk, whether for stimulation, escape, identity, or validation, allows for more conscious choices. Structured outlets for adrenaline, such as sport, performance, and adventure activities, can offer intensity while reducing harm. Calculated challenge expands experience. Self-destructive impulses endanger it. Adrenaline sharpens perception and silences doubt, but its effects are temporary. The true measure of vitality is not found in flirting with harm, but in living fully with awareness and intention. Chasing the rush is compelling, but survival and thriving depend on drawing a clear line between intensity and danger.