A spectrum suggests range. It implies measurable variation, a gradual shift between distinguishable states. In physics, it is light refracted into visible color. In psychology, it is temperament distributed across gradients of intensity. In biology, it is development unfolding through stages. A spectrum promises direction and difference. It offers the reassurance that movement can be traced. We are inclined to imagine the human condition in similar terms. We picture ourselves progressing along a line from fragility to strength, from dependence to dominance, from uncertainty to authority. We assume the higher end must be superior because it appears elevated. We treat life as ascent. We rarely question whether the summit is the point. Yet the human spectrum is less linear than we prefer. It bends. It doubles back. It loops inward. The most consequential transformation may not occur at the furthest extreme but at a quieter coordinate along the way, a precise intersection we pass too quickly while aiming for something grander. That intersection is the spot.

To understand the spectrum, it helps to begin with an animal whose existence is defined by placement upon it.

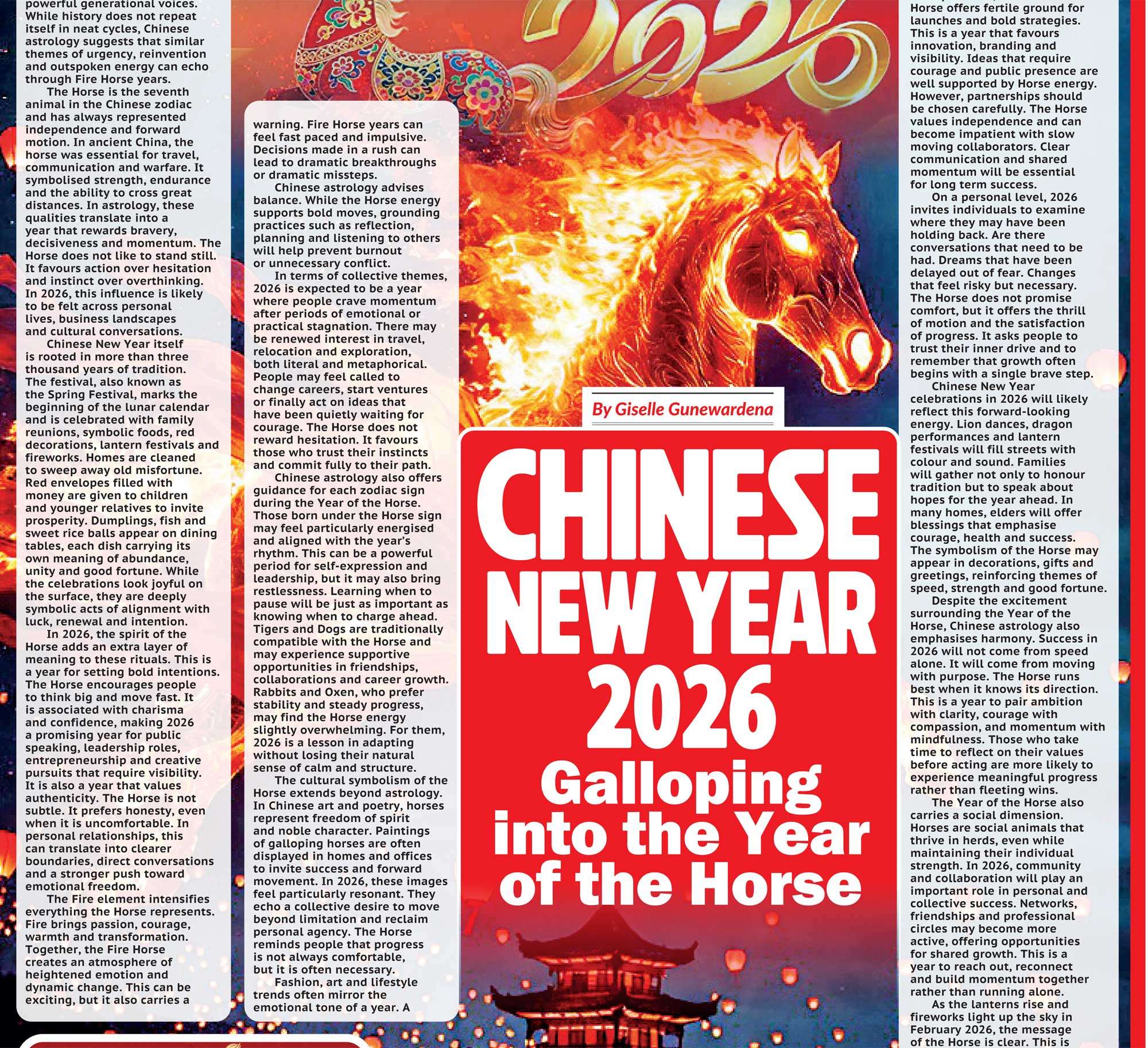

Consider the deer. The skin of a deer carries softness in its architecture. Pale brown scattered with white spots, large lateral eyes positioned for peripheral awareness, slender limbs designed for flight rather than fight. Even before it moves, it appears gentle. Innocence. Vulnerability. Youth. Evolutionary biology would describe the deer as a prey species. Its morphology reflects adaptation to predation pressure. Wide visual fields detect movement. Acute hearing registers the faintest disturbance. Musculature stores explosive energy for sudden escape. The deer survives by attention. Its life depends upon vigilance.

We too begin at that end of the spectrum. At birth, we are wholly dependent organisms. Our first nourishment is drawn from another body. Maternal blood is metabolically transformed into milk, which becomes our earliest interface with the external world. We begin as receivers. Our physiology requires care. Our nervous system develops in response to touch, sound, and proximity. We are shaped by protection and by need. In developmental psychology, this period is characterized by attachment. Security is the foundation upon which autonomy is later built. The deer phase of human life is necessary calibration.

The deer occupies what seems like the beginning of the spectrum. Vulnerability. Sensitivity. Openness.

At the opposite end stands another figure.

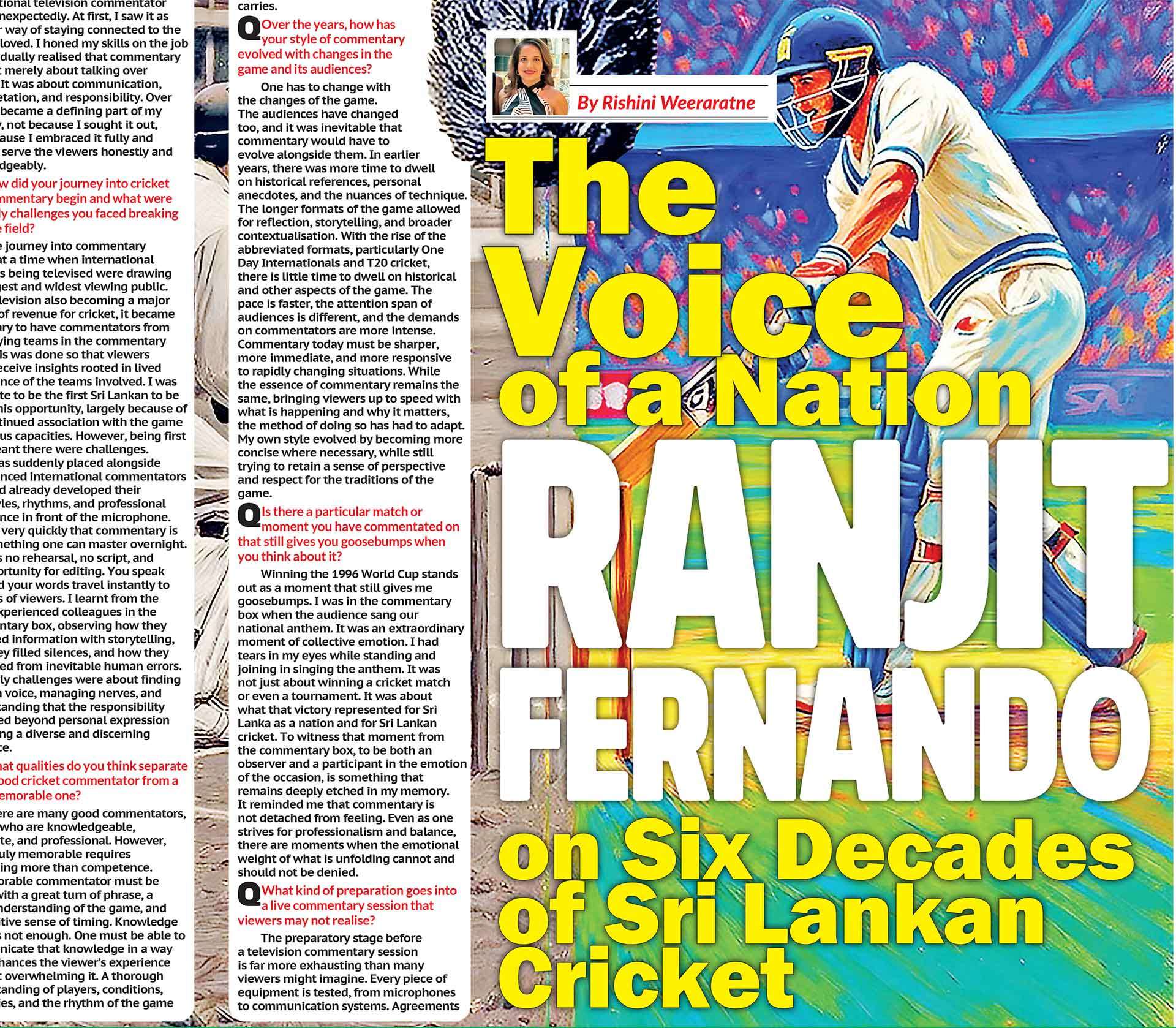

The leopard does not wait to be defined. Its coat bears rosettes rather than spots, darker patterns that disrupt outline and signal authority. It is solitary, muscular, territorial. Where the deer’s eyes scan for danger, the leopard’s eyes calculate opportunity. It hunts. It selects. It exerts force. Hot, isn’t it? In ecological terms, the leopard is an apex or near-apex predator in many of its habitats. Its physiology reflects strength and precision. Power is metabolically expensive, but it confers dominance within a given range. Survival is achieved through control. Human culture has long been fascinated by the leopard’s symbolism. To wear leopard print is often to signal independence, sensuality, defiance. It suggests maturity and command. It implies that one has moved beyond fragility into agency.

In psychological development, this phase corresponds with individuation. We detach from primary caregivers. We earn. We decide. We critique systems rather than merely adapting to them. We acquire the ability to influence outcomes. There is strength here. There is also fire. But power is energetically demanding. Neurobiological studies on stress demonstrate that sustained dominance and vigilance can elevate cortisol levels and strain the body. Supremacy isolates. Territory requires defense. What feels like independence may evolve into chronic exertion. The hotter the print, the faster it burns.

Between deer and leopard lies a region less visible but more consequential. Integration.

The mistake many of us make is believing that maturity requires abandoning the deer entirely. We equate softness with immaturity. We treat vigilance as insecurity. We hurry toward the leopard because it appears to represent success. We forget that the deer survives too, and often for longer. In truth, the deer’s vigilance is a form of intelligence. It reflects adaptive sensitivity. Softness does not negate resilience. Resilience is, in many definitions, the capacity to respond flexibly to stressors.

The leopard’s strength, when tempered with awareness, becomes leadership rather than destruction. Power informed by perception is sustainable. Agency balanced with empathy prevents isolation. The human spectrum therefore does not move cleanly from prey to predator. It oscillates. It revisits earlier states with new understanding. It invites us to inhabit both patterns simultaneously. And it is here that the notion of the spot becomes relevant. The spot is not an endpoint on the spectrum but a coordinate where its forces equilibrate. It is that precise, almost sacred space where vigilance and authority coexist.

Subjectively, the spot can feel elevated, almost cloudlike. When individuals describe experiences of flow, a psychological state identified by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, they often speak of effortlessness following intense effort. We give this experience different names. Pinnacle. Climax. Fulfillment. Spiritual stillness. Balance. The terminology shifts with discipline and culture, but the phenomenon is consistent. Balance, in this context, is not mediocrity. It is dynamic equilibrium. In physiology, homeostasis refers to the body’s ability to maintain internal stability while adapting to external change. Too far in either direction, and systems falter. Balance is not static. It is active calibration.

To illustrate this, consider a sunset. From the shore, the spectacle appears ethereal. The sky transitions through wavelengths of light filtered by atmospheric particles. Shorter blue wavelengths scatter, allowing longer reds and oranges to dominate perception. The horizon glows. From a distance, it appears perfect, framed by sand and sea. But wade halfway into the water and the experience changes. The angle shifts. Refraction alters perception. The glare intensifies. What seemed seamless fragments into brightness and shadow. The closer one attempts to inhabit the horizon, the more elusive it becomes.

There is a lesson embedded in optics. Beauty often depends on position. The spot from which something is observed influences its integrity. The same principle applies to human striving. The spot, whether understood as balance or fulfillment, is most luminous when approached with reverence rather than conquest. The desire to own it can distort it. Yet the spot is not an object to be seized. It is a state to be entered lightly.

Without preparation, a pinnacle feels hollow. Achievements obtained without internal alignment often fail to satisfy. Without patience, climax becomes transient rather than transformative. Without humility, balance collapses into imbalance, as overconfidence blinds us to necessary adjustment. The deer reminds us to pay attention. The leopard reminds us to act. The spot asks us to know when to do which.

An animal that always flees will starve. An animal that always fights will perish. The capacity to switch strategies according to circumstance enhances fitness. Humans are no different. Our greatest asset may not be dominance or vulnerability alone, but discernment.

Do not rush to the far end merely because it gleams. Do not abandon the sensitivity that once protected you. Do not mistake possession for presence. And meaning, perhaps, is the truest form of balance.