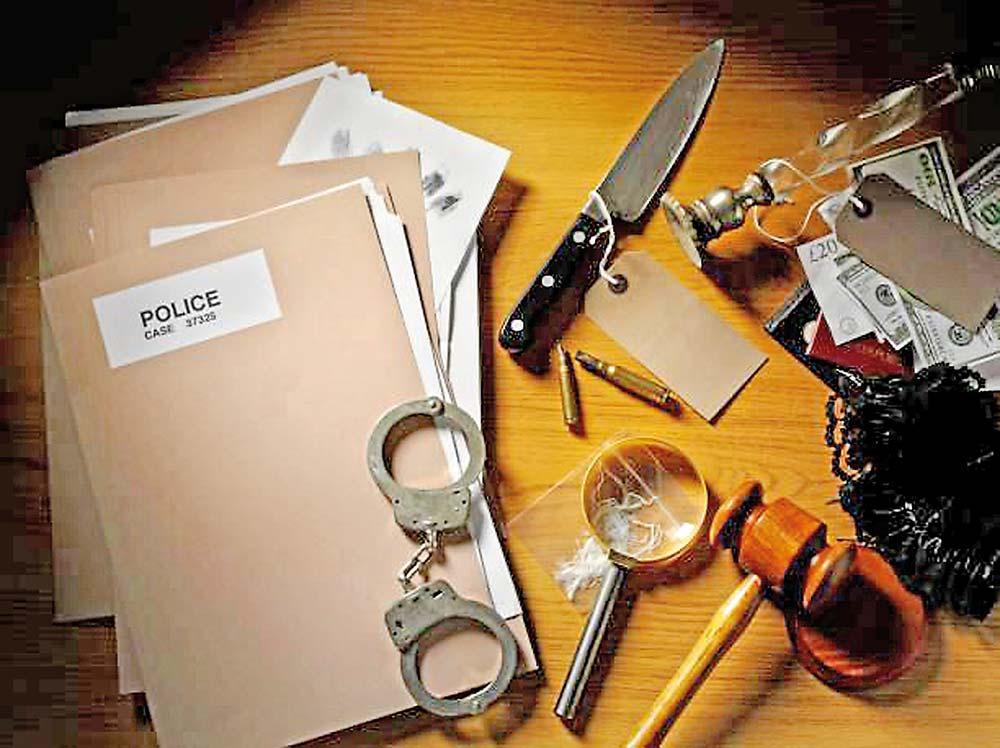

It’s 1:03 a.m. You’re in bed, one earbud in, phone face-down beside your pillow. A low, deliberate voice narrates the grisly details of a decades-old murder. The small Midwestern town, the missing girl, the neighbor who swears he saw her walking home. The music swells just before the ad break. You tell yourself you’ll only listen to half the next episode. You don’t. True crime, once the niche territory of late-night TV reruns and dusty paperbacks, has transformed into a pop-culture juggernaut. From Netflix docuseries and blockbuster films to an ever-growing army of independent podcasts, the genre dominates entertainment charts, and our late-night routines. But behind the ratings, hashtags, and binge-worthy cliffhangers lies an uncomfortable question.

When we devour stories of real violence, are we witnessing injustice or consuming someone’s trauma for entertainment?

The Allure of the “Safe Scare”

Humans have been telling crime stories for centuries. From Victorian penny-dreadfuls to Agatha Christie mysteries, there’s always been an appetite for tales that mix danger with distance. Psychologists call it the “safe scare” the thrill of fear without actual risk. We lean into our primal curiosity about danger, but from the safety of our living rooms. Interestingly, women make up the majority of true crime audiences. A 2023 Spotify study found that nearly two-thirds of frequent true crime podcast listeners identify as female. Some psychologists suggest this isn’t simply morbid fascination; it’s a form of safety research. Listening to stories of how crimes unfold, women say, can help them feel better prepared to avoid becoming victims themselves. Others credit the emotional connection that true crime storytellers create a deep sense of empathy for victims and outrage at injustice. But there’s a difference between learning from a tragedy and turning it into a binge-worthy cliffhanger.

When Storytelling Crosses the Line

For every meticulously researched, victim-centred documentary, there’s a show that blurs fact and fiction for dramatic effect. Add in eerie sound design, stylised re-enactments, and charismatic hosts, and the line between journalism and entertainment begins to fade. Some families of victims say they have been blindsided, finding out their loved one’s case is the subject of a hit show only after seeing a trailer or scrolling past it on Netflix. Others have criticized creators for getting facts wrong, speculating irresponsibly, or inserting fictionalized dialogue for dramatic flair. In 2022, the family of one murder victim publicly asked viewers to boycott a popular true crime series about their relative’s death, calling it “cruel” and “exploitative.” Their grief was reignited not because the crime was discussed, but because it was marketed as content, complete with teaser clips and trending hashtags. It raises an uncomfortable truth: when a tragedy becomes entertainment, whose story is it to tell?

The Business of Tragedy

True crime isn’t just popular, it’s lucrative. Podcasts like ‘Serial’ and ‘My Favorite Murder’ draw millions of listeners and sponsorship deals worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Streaming giants compete fiercely for exclusive documentary rights, often paying significant sums for gripping cases. But the financial flow is rarely towards victims’ families. In many cases, the people directly affected by these crimes see nothing from the profits. The tragedy becomes a commodity, the narrative shaped not for justice or healing, but for clicks, ratings, and ad revenue. That doesn’t mean every creator is unethical. Some work closely with families, share proceeds with victim support organizations, or focus on systemic issues, wrongful convictions, investigative failures, underreported crimes. But the industry’s scale means that thoughtful, consent-driven productions often get drowned out by sensationalized ones.

Consent: The Missing Piece

Legally, most true crime content doesn’t require consent from victims’ families, court documents, police reports, and media archives are often public record. But morally, the consent question is far more complex. If you’ve lost a loved one to violence, should strangers have the right to package and sell your grief without warning? Should they be able to dramatize your relative’s final moments for millions to watch over dinner? Some countries have debated “victim notification” laws for true crime productions, but enforcement is tricky, especially when the internet allows global distribution. For now, the burden largely falls on creators to self-regulate, and for audiences to question the ethics of what we consume.

Listening Without Exploiting

Ethical true crime is possible, and it can be powerful. Here are some signs a podcast, book, or series is telling the story responsibly:

- Victim-First Focus: The narrative centers on the life of the victim, not just the violence.

- Family Involvement: Producers work with relatives or advocates where possible.

- Fact-Checked Research: No speculation dressed as fact, no sensationalized embellishments.

- Contextual Depth: The story addresses systemic factors, policing gaps, social inequalities, not just the crime itself.

- Proceeds with Purpose: Creators donate a portion of profits to relevant charities or legal funds.

As listeners or viewers, we also have power. We can choose to support creators who prioritize ethics over shock value. We can avoid shows that commodify suffering without care. We can be curious, but also critical.

Why This Matters for Culture

True crime isn’t going away. In fact, with AI-enhanced research tools and ever-cheaper production equipment, we’re likely to see even more independent creators entering the space.

And that’s not inherently bad. Some of the most important investigative breakthroughs, wrongful conviction reversals, cold case progress, have come from tenacious independent journalists and podcasters. But our cultural obsession has ripple effects. When murder becomes “content,” it risks desensitizing us to real suffering. When podcasts treat death like a cliffhanger, they blur the line between empathy and voyeurism. And when the business model rewards speed and sensationalism over consent and accuracy, justice takes a back seat to entertainment value.

A Lifestyle Perspective: The “Consumption Code”

Think of ethical true crime like sustainable fashion or fair-trade coffee: consumption still happens, but you can choose how you engage.

- Know the Source: Just as you’d check where your clothes were made, look at how the story was researched.

- Consider the Impact: Ask yourself: would I be comfortable if this were about someone I loved?

- Balance with Action: Use your interest to support advocacy groups or legal funds. Turn passive listening into meaningful contribution.

This isn’t about cancelling a genre, it’s about reframing our role from passive consumers to conscious participants.

As you close the last episode of that gripping podcast or finish a documentary series, pause for a moment. Behind the haunting music, the meticulous narration, the twist ending, there was a real person. They had friends, routines, hopes, flaws, a favorite song, a laugh someone still misses. We owe them and ourselves - the decency to remember that their life is more than the plotline we just consumed. The next time you hit “play,” ask yourself: Am I here to witness their story, or to binge their pain?