It Revealed What Women Fear Most About Love

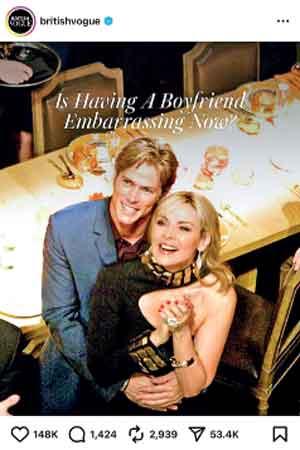

In her British Vogue piece “Is Having a Boyfriend Embarrassing Now?”, writer and activist Chante Joseph examines a fascinating social shift: the collective recoil from what she calls “Boyfriend Land,” an era when a woman’s social currency was often tied to her romantic attachments. Joseph’s essay succeeds because it does what good cultural writing should, it observes the absurdity of the present with irony and introspection. Beneath the humour lies something far more profound: a quiet reckoning with womanhood, visibility, and the politics of intimacy in the digital age.

In her British Vogue piece “Is Having a Boyfriend Embarrassing Now?”, writer and activist Chante Joseph examines a fascinating social shift: the collective recoil from what she calls “Boyfriend Land,” an era when a woman’s social currency was often tied to her romantic attachments. Joseph’s essay succeeds because it does what good cultural writing should, it observes the absurdity of the present with irony and introspection. Beneath the humour lies something far more profound: a quiet reckoning with womanhood, visibility, and the politics of intimacy in the digital age.

As someone who has watched this shift unfold in real time, I find Joseph’s observations painfully accurate. The modern internet woman has become fluent in what I would call romantic discretion, a semiotic game of implication rather than revelation. Gone are the hard launches of boyfriends and engagement rings. In their place, we see cropped hands, empty dinner tables, or the faint outline of a man’s shoulder. Relationships are no longer proof of success; they are potential liabilities. What once was a symbol of status is now something to hide in a Story highlight.

Joseph opens her essay with exasperation at the fatigue of seeing one too many “my boyfriend”-centric accounts. It is an emotion many women recognize but rarely confess. Once, love was a spectacle. We curated it, performed it, and sought validation in its display. Now the performance itself feels gauche, even regressive. Joseph suggests this is partly because we have grown allergic to the optics of dependency. The internet rewards self-sufficiency and irony. The woman who appears unattached, self-contained, and impervious to male influence becomes aspirational. To be visibly in love, especially with a man, risks being seen as naïve or, worse, traditional.

Here, Joseph’s writing captures the paradox of our generation’s feminism. Women want to love and be loved, but not at the expense of their autonomy or their brand. She writes that “women want the prize and celebration of partnership, but understand the norminess of it.” That word, norminess, is crucial. It signals not only banality but also conformity. The internet’s collective psyche now associates public heterosexuality with something outdated, even embarrassing. Yet beneath the sarcasm, Joseph is writing about something tender: fear.

Here, Joseph’s writing captures the paradox of our generation’s feminism. Women want to love and be loved, but not at the expense of their autonomy or their brand. She writes that “women want the prize and celebration of partnership, but understand the norminess of it.” That word, norminess, is crucial. It signals not only banality but also conformity. The internet’s collective psyche now associates public heterosexuality with something outdated, even embarrassing. Yet beneath the sarcasm, Joseph is writing about something tender: fear.

Fear of being seen as the kind of woman who orbits her life around a man. Fear of the mockery that follows every public breakup. Fear of the evil eye, of envy, of losing both love and face. Her respondents confess to superstition and self-protection. They do not want to invite scrutiny into what feels sacred. One woman tells her, “Even though I am a romantic, I still feel like men will embarrass you even 12 years in.” That line, both funny and tragic, captures the exhausted realism of our time. Love, especially heterosexual love, has become something to endure rather than exhibit.

As a woman in her twenties, I understand this exhaustion intimately. It isn’t that we’ve grown cynical about love, it’s that love has begun to feel like a performance, carefully staged and endlessly critiqued. Somewhere between advice columns, podcasts, and algorithm-approved relationships, an invisible checklist appeared. He should text first. He should plan thoughtful dates. He should know your love language, be emotionally fluent yet not fragile, masculine but soft, protective but not possessive. He should post you sparingly, and give you space, but not too much of it. He should play no games, yet somehow keep things interesting.

And when he falters, even slightly, there is a chorus waiting: friends, followers, the omnipresent internet, each with their own verdict. Love, once a private tenderness, now feels like a group project, subject to commentary, reaction, and review.

And why do we care? Because we do. Because none of us want to look like the fool; the one who loved too loudly, trusted too soon, stayed too long. We want to believe we are being loved in the way love is supposed to look, the way it has been defined and displayed by everyone else. And maybe, deep down, we know the critics are not always wrong. So, we play it safe. We protect our image as fiercely as our hearts, terrified that vulnerability might one day turn into public embarrassment.

And why do we care? Because we do. Because none of us want to look like the fool; the one who loved too loudly, trusted too soon, stayed too long. We want to believe we are being loved in the way love is supposed to look, the way it has been defined and displayed by everyone else. And maybe, deep down, we know the critics are not always wrong. So, we play it safe. We protect our image as fiercely as our hearts, terrified that vulnerability might one day turn into public embarrassment.

This constant external evaluation has made intimacy feel performative even when it is not. The woman who chooses love for its simplicity risks being seen as complacent. The woman who hides it completely is applauded for her restraint. It is an impossible balance, and Joseph captures this duality with remarkable subtlety. She does not mock women for their evasions, nor does she mourn the loss of the old romantic spectacle. Instead, she recognizes that this new restraint is a form of rebellion, an attempt to reclaim privacy from the hungry gaze of the internet.

Still, I wish Joseph had gone further. Her essay touches on something more existential: the quiet collapse of the shared myth of love in the digital age. If love once validated us, what happens when it becomes a source of embarrassment? When affection itself is perceived as cringe? To understand this shift, one must look beyond gender politics into a deeper cultural mood of disillusionment. The internet has taught us to pre-empt heartbreak with irony. Vulnerability has been replaced by detachment. Even the word boyfriend feels too earnest, too pedestrian, for an era obsessed with curation. We prefer “seeing someone” or “talking to someone,” phrases that keep us conveniently uncommitted.

Joseph briefly references writer and influencer Stephanie Yeboah, who lost followers after posting about her relationship. It is a small anecdote, but it reveals a larger phenomenon: the suspicion of happiness. Audiences, especially women, do not want to be reminded of a femininity that feels outdated or unattainable. It is not only that boyfriend content has become dull; it is that it disrupts the fragile equilibrium of shared cynicism that sustains much of the internet’s tone.

Joseph briefly references writer and influencer Stephanie Yeboah, who lost followers after posting about her relationship. It is a small anecdote, but it reveals a larger phenomenon: the suspicion of happiness. Audiences, especially women, do not want to be reminded of a femininity that feels outdated or unattainable. It is not only that boyfriend content has become dull; it is that it disrupts the fragile equilibrium of shared cynicism that sustains much of the internet’s tone.

When Joseph writes that “being partnered doesn’t affirm your womanhood anymore,” she captures a seismic cultural shift. For centuries, womanhood was measured through relational milestones, marriage, motherhood, attachment. The digital feminist era has dismantled those markers, but what remains in their absence is a strange limbo between freedom and fatigue. Freedom, because we are no longer bound by expectation. Fatigue, because the constant vigilance required to appear above it all is exhausting. Refusing sentimentality has become its own kind of work.

This is where Joseph’s essay feels both liberating and melancholic. The question “Is having a boyfriend embarrassing now?” may sound flippant, but it reveals the tension of our age: the coexistence of desire and disdain. We still want connection, but we have been trained to disguise it as irony. We crave intimacy, but only if it does not make us look soft.

In the end, Joseph’s essay is not really about boyfriends at all. It is about the performance of self. It is about the woman who has learned to curate even her affection, to turn love into aesthetic, and to weaponize privacy as a form of power. Yet somewhere within this aesthetic restraint lies another quiet sadness, the erosion of the shared joy of public love. There was once something beautifully human about the simple act of declaring one’s affection. Not the influencer’s overshare, but the unfiltered pride of saying, “this is the person I love.”

We have lost that innocence. Our romance now passes through filters of irony, strategy, and discourse. Perhaps, as Joseph implies, this is progress, an overdue correction to centuries of heteronormative mythology. Yet one wonders whether, in rejecting the archetype of the “boyfriend girl,” we have also abandoned a certain warmth.

Love was never meant to be performative, but it was always meant to be shared. If, in our pursuit of composure, we have learned to hide the very thing that makes us most human, then the real question is not whether having a boyfriend is embarrassing. The question is why vulnerability itself has become so unfashionable.