For centuries, literature and media have offered us a simplified binary: good versus evil. It's clean. It's convenient. The hero wins, and the villain loses, restoring order. But morality doesn’t live in black and white; it dances in the grey.

Flipping the Script on Morality, Monsters, and Misunderstood Rebels

Every good story needs a villain, or so we've been told. The antagonist who snarls, schemes, and threatens the very fabric of justice. They're the shadow to the hero’s light. The problem to be solved. The evil that must be defeated. But what if the villain wasn’t wrong?

What if the so-called villain was merely someone society failed to understand? Someone born into a system that pushed them to the edge, then punished them for reacting?

- Maybe villains aren’t born.

- Maybe they’re created.

- Molded by rejection, injustice, and the very heroes we’re told to cheer for.

Villains Are Society’s Emotional Dumping Grounds

For centuries, literature and media have offered us a simplified binary: good versus evil. It's clean. It's convenient. The hero wins, and the villain loses, restoring order. But morality doesn’t live in black and white; it dances in the grey. Villains are often used to project collective anxieties. They carry the burden of being everything we fear, hate, or don’t understand. But when we slow down and actually listen to their backstory, we start seeing not a monster, but a mirror. Let’s look at a few of these so-called villains who might’ve just been right all along.

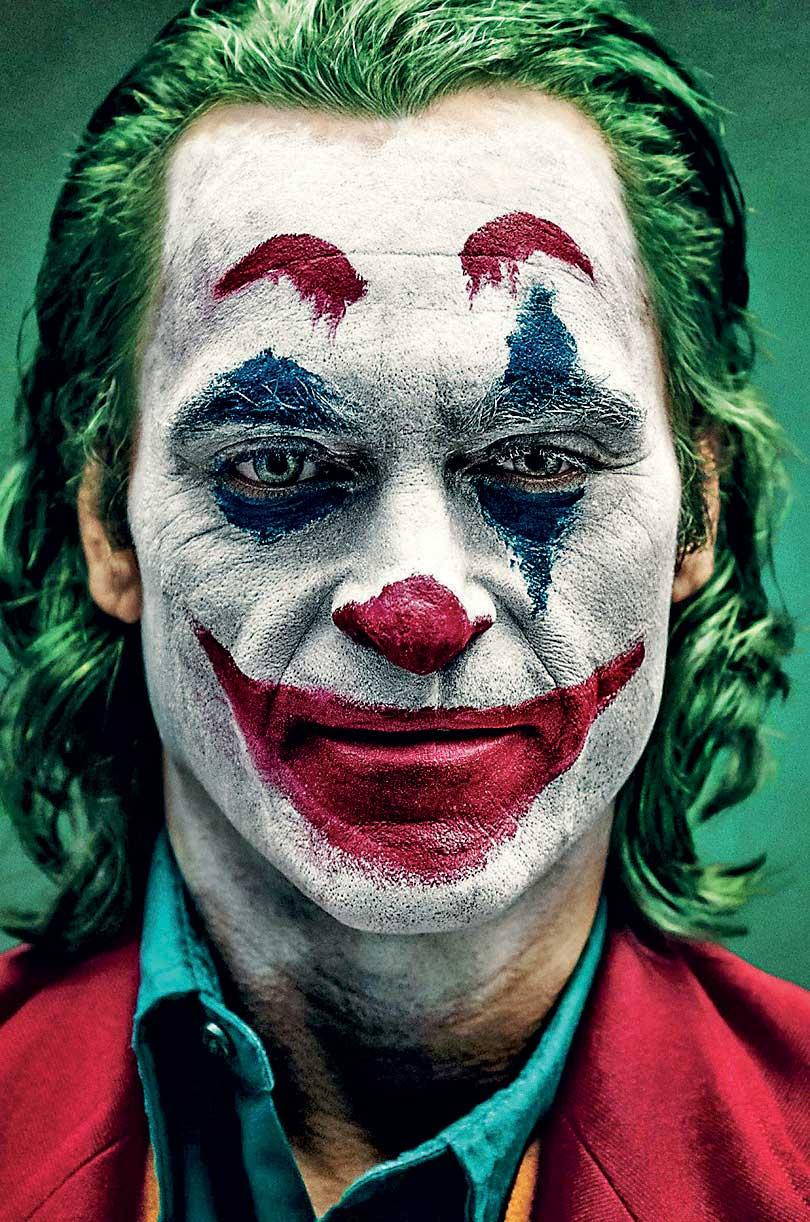

The Joker: The Clown of Chaos or the Cry for Help?

The 2019 film Joker, starring Joaquin Phoenix, cracked open the villain origin story like never before. Gone was the playful psychopath of comic books. This Joker was mentally ill, lonely, and chronically ignored by a system that discarded him.

We watch as Arthur Fleck is mocked, beaten, and stripped of dignity until he breaks. He becomes violent not because he enjoys cruelty, but because the world showed him none. Joker becomes the embodiment of a brutal truth: when society fails to care for the vulnerable, chaos becomes their language. And laughter becomes the mask for unbearable pain. His story forces us to ask: who is really mad, the man, or the system?

Scar from The Lion King: The Overlooked Brother

In the Disney classic The Lion King, Scar is painted as the jealous uncle who murders his brother Mufasa for the throne. Terrible? Yes. Justified? Let’s pause. Scar is the younger brother. He’s intelligent, articulate, and arguably more strategic than Mufasa. But he's constantly sidelined in a monarchy that values brute strength and lineage over intellect or equality. No matter what he contributes, he is reminded that he's second-best, never fit to rule. He lashes out, yes. But can we really expect someone who’s been systematically excluded to remain passive forever? Scar isn’t just evil. He’s a metaphor for how societies alienate those who don't conform to tradition. His villainy is not innate. It’s reactive.

Maleficent: The Villain Who Wasn’t

In the original Sleeping Beauty, Maleficent curses a baby out of spite. Pure, theatrical evil. But the 2014 reimagining starring Angelina Jolie showed us a different tale: one of betrayal, trauma, and loss. Maleficent is violated. Her wings are literally stolen by the man she loved. The curse becomes not just a plot device but a cry of grief. Her wrath isn’t senseless. It’s born of heartbreak, humiliation, and revenge. She’s not a villain. She’s a survivor.

Killmonger from Black Panther: Revolutionary or Terrorist?

Killmonger is perhaps one of the most ideologically complex “villains” in Marvel history. His argument is simple: Wakanda should use its technology to free oppressed Black people worldwide. He’s not fighting for himself. He’s fighting against systemic injustice, colonial scars, and generations of violence. His methods are extreme, but his motivations are righteous. In fact, T’Challa, the hero, evolves because of Killmonger’s challenge. In death, the villain becomes the moral compass.

The Literature of the Damned

Villains in classical literature have always been complicated, but we rarely question the narrative lens.

- Shylock in The Merchant of Venice is portrayed as greedy, but his demand for a pound of flesh stems from years of anti-Semitic abuse.

- Frankenstein’s monster is a tragic figure, an abandoned child in a stitched-up body, rejected even by his creator.

- Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights becomes cruel, but it is the cruelty of classism, racism, and heartbreak that made him what he is.

What all these characters share is a painful truth: they were dehumanized before they became destructive.

Society Creates the Monster, Then Punishes It

When we label someone a villain, we often absolve ourselves from asking hard questions. It’s easier to blame individuals than to examine the environments that shaped them.

- The abused child who grows up angry.

- The poor man who steals because the system offers no support.

- The protestor called a terrorist because he dared to disrupt order.

If we looked closer, we’d see that behind every villain is a human being society gave up on.

The Hero-Villain Binary is Lazy Storytelling

Let’s face it, many heroes are just as flawed as the villains they defeat.

- Batman beats up mentally ill people instead of funding Gotham’s healthcare system.

- Harry Potter is lauded, but Snape’s complexity is only appreciated in death.

- Katniss Everdeen is called a rebel. But if her story were told from the Capitol’s side, she’d be a terrorist.

The point is: morality is often a matter of perspective. History, too, is written by the victors. And villains rarely get a chance to speak for themselves.

So, What Do We Do With This?

Do we let all villains off the hook? No.

But we must stop painting people as pure evil just because it’s convenient. If storytelling is a mirror, then we must reflect all angles, not just the ones that flatter us.

- Let’s examine the system, not just the symptoms.

- Let’s listen to pain before it becomes destruction.

- Let’s write better stories where villains are not just punished but understood.

Final Thought: Empathy is Not Approval

Understanding a villain’s backstory doesn’t mean justifying their harm. It means recognizing that everyone, even those we fear, comes from somewhere. And maybe, just maybe, the line between hero and villain isn’t who wears the cape, but who got the chance to speak